Autumn 1880. St. Petersburg society is talking about an unprecedented event: the exhibition of just one painting. Never before has this happened in Russia, and the line of people outside building of the Imperial Society for the Encouragement of Arts stretches around several blocks.

Everyone wants to get a glimpse of the new picturesque seascape Moonlit Night on the Dnieper, for which Grand Duke Konstantin Romanov paid a fabulous amount even before it was finished. Meanwhile, its creator, Arkhip Kuindzhi, adopts a marketing ploy: he covers all the windows in the room with curtains and displays the picture in the dark, directing a single ray of electric light at it. The effect is staggering. Viewers do not believe that such a "phosphoric" glow of moonlight on the water surface can be achieved with ordinary paints.

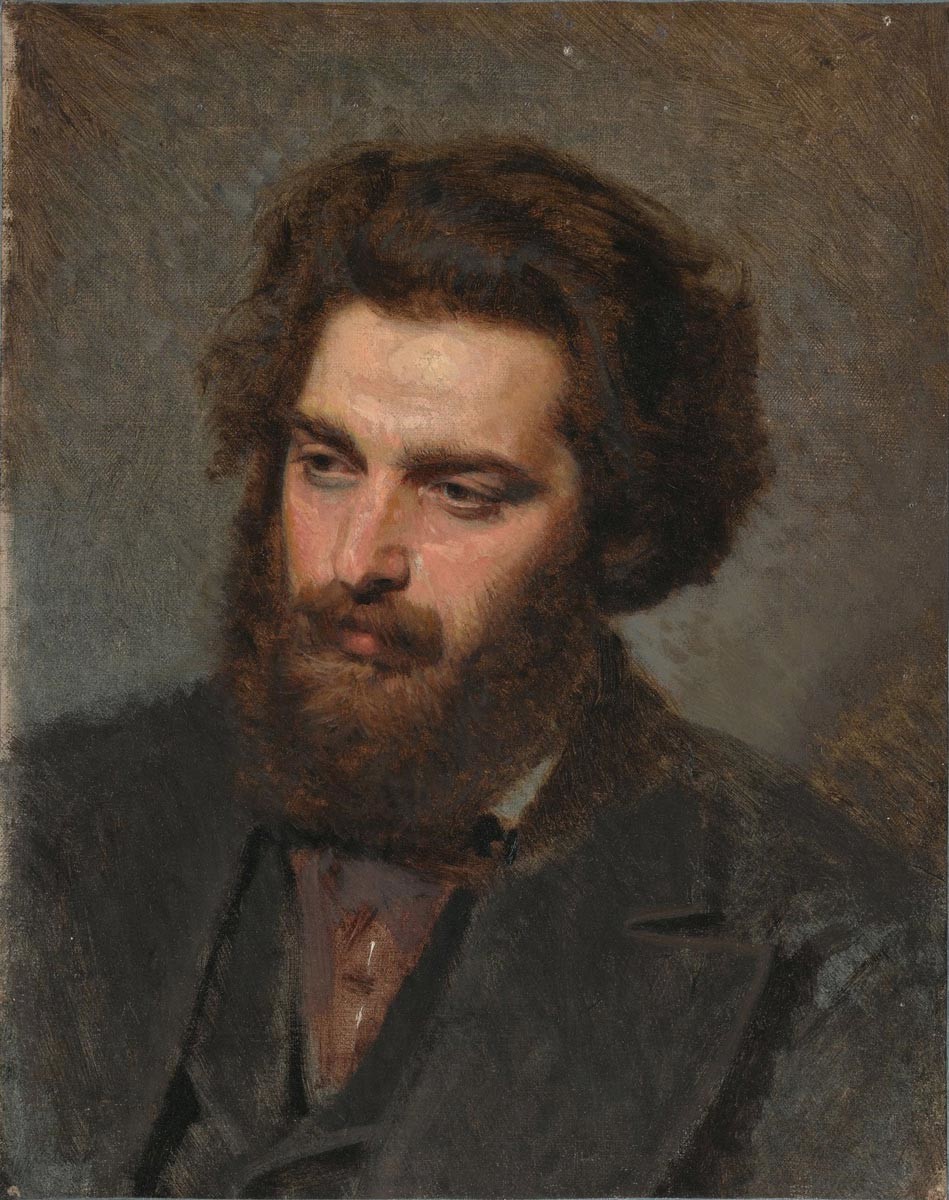

Kuindzhi is labelled a hoaxer and accused of using hidden lighting. But there is no backlight, of course. “The illusion of light was his god, and no artist could equal in achieving this painting miracle,” said fellow Russian artist Ilya Repin about his colleague. This incredible sense of color won Kuindzhi a place in the history of art as one of the main experimenters of the 19th century.

Kuindzhi painted his most celebrated work shortly after parting company with the Itinerants (a group of realist artists who opposed Academism in art). And he managed to sell it to the grand duke even before completing the canvas: writer Ivan Turgenev was so enraptured by the work that he persuaded the duke to buy it. The latter even took it with him on trips: Night was exhibited for several days at the Sedelmeyer Gallery in Paris. There are several versions of the picture, made by the artist when he realized the extent of his own popularity.

The Birch Grove was painted a year before Moonlit Night on the Dnieper, but already fully demonstrates Kuindzhi’s main stylistic principle of spectacular chiaroscuro. That was when the public began to suspect the use of optical tricks, which provoked a scandal.

Kuindzhi regularly visited Valaam Island in Karelia, a popular place for St. Petersburg landscape painters. Bought by the collector and founder of the Tretyakov Gallery, Pavel Tretyakov, this picture marks the start of his fame as a serious artist. The style of the Itinerants is clearly traceable — the deliberate realism was very much admired by contemporaries.

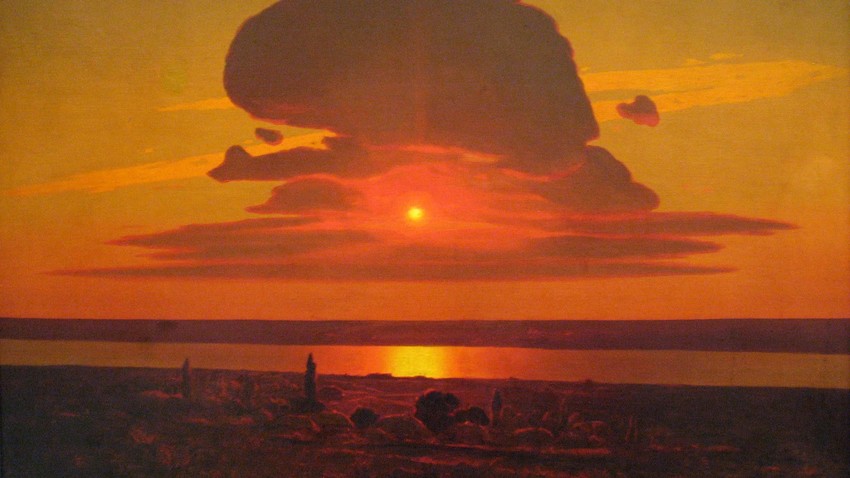

The artist worked on this painting for a total of 23 years. And 20 of them he spent in voluntary seclusion, during which time Kuindzhi did not show his works to anyone, even friends and family. It is not known for certain what caused him to “fall silent” at the peak of his fame, but many believed then that he was fatigued by the constant hype and criticism. The “Evenings in Ukraine” exhibition plus three other paintings broke the “silence”.

Kuindzhi is closely associated with Crimea, the subject of dozens of his works. It was here that the future artist came as a young man, having decided to take his passion for drawing further: he was recommended as a student to the famous seascape painter Ivan Aivazovsky, who lived in Crimean coastal town of Feodosia. True, the great Aivazovsky could not spare the time, but he gave Kuindzhi a letter of recommendation. Already a big-name artist, Kuindzhi painted the “immersive, meditative” Sea. Crimea, in which the Crimean shoreline is dappled in rich hues.

Another of his Crimean landscapes is dedicated to Ai-Petri, a mountain ridge near Yalta and one of the symbols of the peninsula. In 2019, this painting was stolen from the Tretyakov Gallery in broad daylight in full view of dozens of visitors. A man in overalls simply went up to the canvas, took it off the wall, removed it from the frame and walked out with it. It was the thief’s composure that fooled everyone: people genuinely believed he was a museum employee. He was detained the next day, and the painting was returned to the museum.

This was among the four paintings that Kuindzhi decided to show after his “silent” period. It is perhaps the master painter’s most philosophical and mysterious work, and the only one on a biblical theme. But, as in all his oeuvre, it is not the subject, but the light and color that take center stage. Through it, without the need for intricate details, the artist reveals the drama of the situation. Bathed in moonlight, the figure of Christ is snatched out of the darkness, an effect that strongly resembles Moonlit Night on the Dnieper.

The vivid, temperamental contrast of the storm clouds with the peace and tranquillity of the meadow accurately conveys the light atmosphere that follows a downpour.

Art critics remark that his landscapes evoke almost sound and sensory associations in the viewer: be it a light morning wind, wet grass or the rarefied air after a thunderstorm.

One of Kuindzhi’s last great works. According to critics, the artist comes across in this picture as a pagan sun worshipper. The canvas had a complicated fate: it was repeatedly resold before ending up at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox