Vasily Vereshchagin gained fame as a battle scene painter; war is the main topic of his works. However, you won’t see grand battles, triumphant marches, or victorious officers in his paintings. He did not depict the “parade” side of the civil war in Turkestan, but rather its consequences and the horror behind resounding victories. ‘The Apotheosis of War’ was one of those paintings. There was a carved message on the frame of the painting: “To all great conquerors, past, present and to come.” The artist conceived the idea of this painting as the culmination of his Turkestan series. But, when Vereshchagin presented his work in St. Petersburg, it spurred long, heated debates. It was considered a powerful reproach against Russia’s imperial ambitions and official authorities denounced Vereshchagin’s works. The elite of the time, meanwhile, completely ignored his works. The painter found it hard to cope with this; in the state of a nervous breakdown, he burned three other paintings of the series that were also targets for especially fervent criticism.

This painting by Ilya Repin evokes mixed emotions even today. For example, in 2018, an unemployed man from Voronezh by the name of Igor Podporin pounced on it at the exhibition ‘To Moscow! To Moscow! To Moscow!’ in the capital. His plan was to destroy the painting; after he was apprehended, he described his motive thus: “I was very much outraged by this Repin guy’s painting. Foreigners come here, if they see it – what will they think about our Russian tsar? And about us? This is a provocation against the Russian people, so others would treat us badly.”

According to the narrative, Ivan the Terrible holds his dying son Ivan in his hands, whom he himself has killed. Really, historians couldn’t find any information that would refute this legend, so this question has always caused a heated debate. Some have pointed out the historical inaccuracy of the narrative, while others blame the painter for his disrespect towards authorities and for defamation.

The authorities themselves, after the first exhibition, reacted in unison – they banned the painting. “Today, I saw this painting and couldn’t look at it without disgust. <…> A surprising work today without any ideals, only with the feeling of bare realism with a tendency for criticism and denunciation.” – this is what the Chief Procurator of the Most Holy Synod with the last name Pobedonostsev wrote in his letter to Tsar Alexander III.

Vladimir Makovsky. ‘Khodynka’

Public domainGeneric everyday life scenes remain as the best and the most famous among Vladimir Makovsky’s works – with children, peasants and the poor. But, once, the painter witnessed one of the most horrific events during the reign of Nicholas II: he witnessed the Khodynka field tragedy – a mass crowd crush in 1896 during the coronation of Nicholas II on the outskirts of Moscow. Thousands of people then came to claim their promised presents on the occasion of the coronation; many were afraid there wouldn’t be enough presents for them all and began pushing to get to the distribution points. By official data alone, 1,389 people became victims of this tragedy.

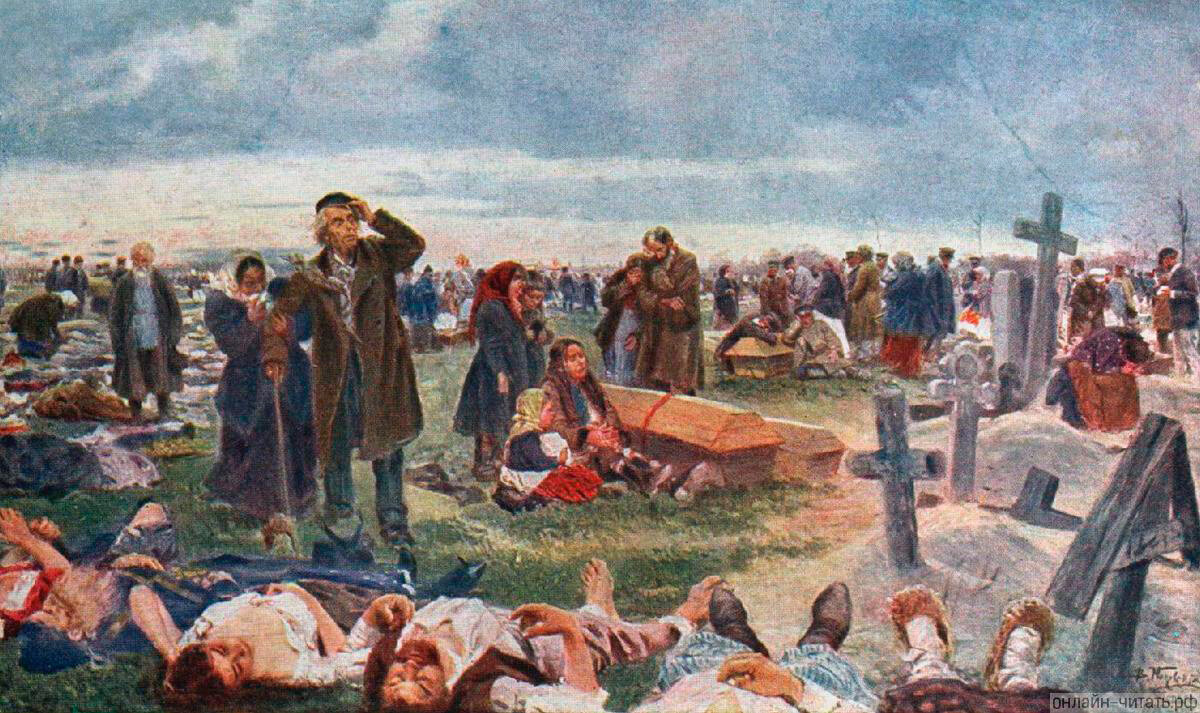

Vladimir Makovsky. ‘After Khodynka. Vagankovo Cemetery’

Public domainThe death of these people shook Makovsky. The artist was supposed to create a painting following the end of this event and he eventually did after the tragedy. For the next five years, he worked on his paintings ‘Khodynka’ and ‘After Khodynka. Vagankovo Cemetery’. The victims of the crush were depicted in the paintings. In 1901, ‘Khodynka’ was removed from the Peredvizhniki exhibition, following the censorship decision. The artist was handed a note from the Governor-General of Moscow which said: “It’s not yet time for this painting, it is salt poured on an open wound.”

This painting by Nikolai Ge depicts an episode from Procurator Pontius Pilate’s trial of Jesus Christ, specifically when Pilate asks Jesus a question that was left then unanswered. This painting was first presented at a Peredvizhniki exhibition in 1890, but caused a strong reaction and was removed from the exposition by the order of the Holy Synod.

The thing is, it wasn’t aligned then with neither cultural nor church nor artistic tradition. Jesus stands in the dark shadow, while the figure of Pontius Pilate basks in sunlight – this contradicted the old tradition of interpreting Jesus as a man of absolute light. Jesus looks exhausted and small, bereft of significance in comparison to the procurator. Not only the Orthodox Church, but also many artists couldn’t accept that. Initially, collector Pavel Tretyakov even refused to purchase this work, but, later, Leo Tolstoy convinced him to change his mind.

In the 19th century, the faith and the church were gradually facing doubt and their images and their servants were facing criticism; Vasily Perov wasn’t the one to stand by, either. According to the Orthodox Church’s opinion, ‘Easter Procession’ turned the image of one of the main religious rituals upside down: the procession doesn’t come out of a church, as it’s supposed to, but out of an old hut; vagabonds litter the ground around, while a drunk priest crushes an egg, one of the symbols of Easter. The entire procession is walking disorderly; there’s emptiness in the eyes of the participants.

The Orthodox Church called this painting “licentious, immoral, arrogant and mocking” and threatened to burn it; they also accused the artist of mocking the image of Russian Christianity. Alexander II himself wanted to send Perov to Siberia. The artist, of course, was not afraid of exile, since he hailed from the Siberian city of Tobolsk. But, the very fact of such a singularly negative reaction makes this painting one of the most provocative among the paintings of the 19th century.

Dear readers,

Our website and social media accounts are under threat of being restricted or banned, due to the current circumstances. So, to keep up with our latest content, simply do the following:

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox