These were the first settlers in America to arrive from Russia. They brought with them their national drink.

Getty Images

This was the first vodka plant in America. It opened in 1934 in Bethel, Connecticut, on the second floor of a small building, following the repeal of Prohibition. But there was one tiny snag: Americans didn’t drink vodka.

Legion Media

This is A.1. Steak Sauce (now A.1. Sauce). It was the main product of Heublein Inc., which bought out the soon-to-go-bust vodka plant and guaranteed the future of Russia’s national drink stateside.

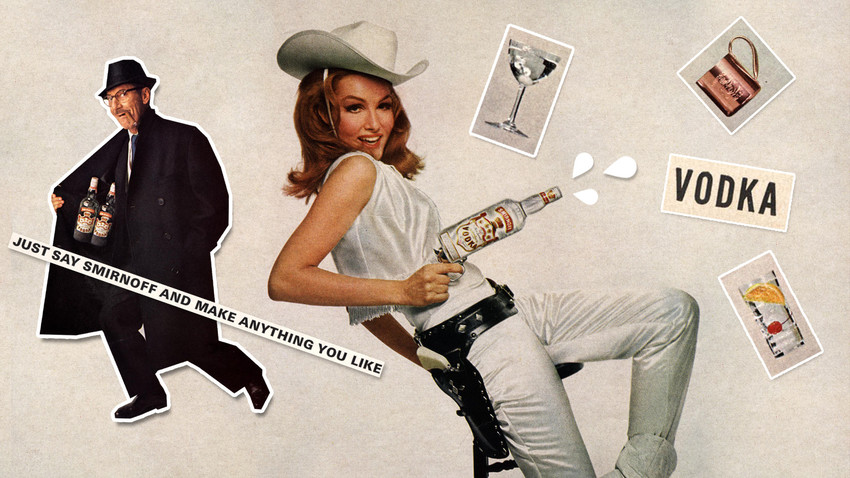

This is one of first ads for Russian vodka. Set to be a flop, it was saved by chance. A trader from Columbia, South Carolina, toyed with a bottle containing the unfamiliar drink... and came up with an intriguing slogan: “White whiskey — no color, no smell, no taste.”

Heublein Inc.

This is a “Moscow mule” cocktail. Once king of the vodka cocktails, it is said to have been born in the bar of Hotel Chatham in Manhattan. Bartenders made it by mixing vodka with ginger beer and lime juice.

Getty Images

Here’s U.S. actor Broderick Crawford, who was one of the first to try a Moscow mule. Impressed, he told his Hollywood colleagues about it.

Legion Media

That was how vodka hit the silver screen and green rooms. By the mid-20th century, its lack of color and smell had made it Hollywood’s favorite drink, since most contracts banned drinking alcohol during filming.

United Artists

Here’s Sean Connery as James Bond, the man who taught America and the world to drink vodka Martini (shaken not stirred, of course). He surreptitiously advertised Russian vodka for 40 years.

AP

This is the banquet table at the Yalta Conference in 1945. General George Marshall raises a glass of Russian vodka to cooperation with the Soviet Union and victory.

Getty Images

In 1950 bartenders went on strike. At the height of the Cold War, vodka was associated with the Soviet Union and poured on the streets. Bartenders demanded a ban on the Moscow mule and vodka, which Moscow was allegedly using to undermine the foundations of US democracy.

Legion Media

It’s a striking example of the old adage that there’s no such thing as bad publicity. Instead of rejecting it, Americans rushed to the bars in droves to find out what the “forbidden” cocktail was all about, and what else this “dangerous” Russian ingredient could be mixed with.

Reuters

This is vodka produced in Siberia. In 2016, vodka in America outperformed whiskey. Americans consumed 69.8 million crates of vodka (almost one in three bottles ordered in bars was vodka), against 53 million crates of whiskey.