How a German doctor moved to Russia and became a saint

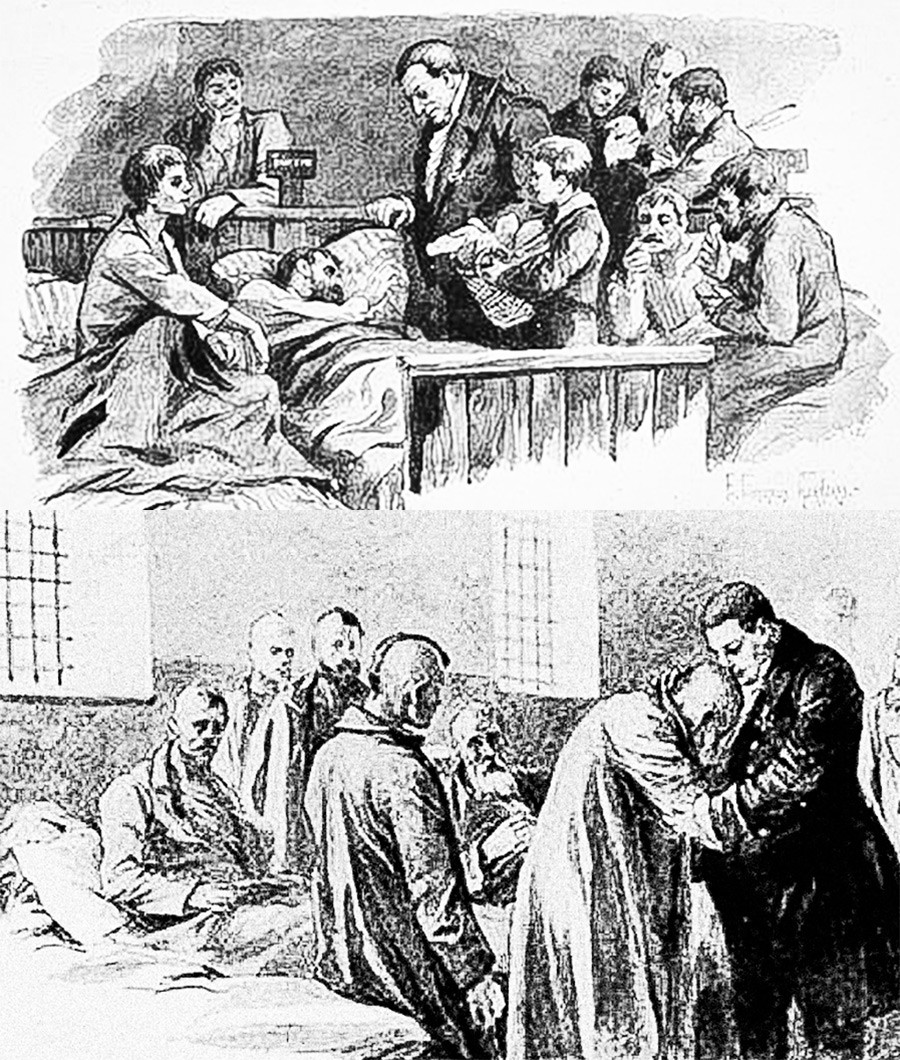

Doctor Haass on the portrait.

Elena Samokysh-SudkovskayaIn The Idiot by Feodor Dostoevsky, one of the characters tells a story of a big-hearted man: “In Moscow, there was an old state counselor, who, all his life, had been in the habit of visiting the prisons and speaking to criminals…”

Sounds very Dostoevskian: “He would walk down the rows of unfortunate prisoners, stop before each individual, and ask after his needs…gave them money; brought all sorts of necessaries…he continued these acts of mercy up to his very death; by that time all the criminals, all over Russia and Siberia, knew him!”

It wasn’t some sinless soul Dostoevsky made up; this man was real, his name was Fyodor (or Friedrich) Haass and he moved to Moscow from Austria in 1806. Starting out as a doctor, he ended up a saint.

From Friedrich to Fyodor

Born in the small German town of Bad Münstereifel, Haass (1780 – 1853) started his practice in Vienna, Austria. In 1806, Russian prince Nikolay Repnin-Volkonsky visited Austria’s capital to seek medical help for an eye injury. Despite being young Haass was already a successful medic and helped. As a result, Repnin-Volkonsky invited him to become his family doctor in Moscow.

“Money, nice company, and big prospects – all of that impressed the young doctor so much that he took the offer,” writes Moslenta.ru. Little did he know that he is going to stay in Moscow for much longer than he expected.

In Russia, Haass settled down: aside from being Repnin’s family doctor, he headed one of Moscow’s hospitals. In 1812, when the French invaded Russia, Haass served as a regimental doctor and went all the way to Paris with the Russian army. Then he came back to Russia, which had become his home by then: he learned the language and changed his name to Fyodor.

Hard time for charity

After inspecting the state of prisons, Haass was shocked. Terrible hygiene, diseases, hunger, violent guards and prisoners... no one seemed to care. “Haass saw only indifference, bureaucratic routine, motionless law, and the whole society opposite to his humane view on the people,” wrote Anatoly Koni, a Russian lawyer

It didn’t stop Haass though, who was a devoted Catholic and well-doer whose motto was “Hurry to do good deeds!” The doctor worked on the Prison Patronage Committee for 25 years and changed the system for the

Reducing the evil

Haass completed multiple good deeds, including changing how prisoners were treated. Namely, he made the government abandon shaving half of prisoners’ heads (regardless of sex) or chaining up to 10 people to a giant heavy bar.

Also, Haass insisted that the shackles

Champion of mercy

Once, during a dispute

Stunned and ashamed, Filaret answered: “No, it seems that Christ left me for a moment” and went out of his way to help Haass from that point on. Even though he was a Catholic, Haass was thought of as a saint in Orthodox Moscow.

Sacrificing everything

Haass refused to stop helping the poor and miserable and the line of those waiting for his help never got shorter. He spent all his money, sold his mansion and horses, moved to a tiny apartment in his clinic, and lived alone and childless for all his life. When Haass died in 1853, the police had to pay for the funeral – the doctor had no savings.

More importantly, Haass was admired by so many that around 20,000 people showed up to his wake. Perhaps for

In 2018, Haass was officially recognized as a saint by the Catholic Church.

As we've already mentioned Dostoevsky, let's have a look at the pearls of wisdom he and other Russian classics shared with the world – we have a text on it.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox