In February 1801, more than 22,000 Cossacks led by Ataman Matvey Platov set off from the Don steppes on an unprecedented campaign through Central Asia and Afghanistan to India.

But thanks to the subsequent efforts of Alexander I to blacken the name of his father, the thwarted Indian campaign has gone down in history as a utopian escapade concocted by the mentally unbalanced Paul.

Many details of the expedition were deliberately consigned to oblivion. Not everyone knows, for instance, that the Cossack campaign was only a small part of a proposed Russian-French invasion of India schemed up by Napoleon Bonaparte himself.

Disenchantment with the British

In the last decade of the 18th century, all European monarchs had one overarching aim—to destroy revolutionary France to prevent its infectious ideas from spreading to their states.

Among them was the Russian Empire. On land, Alexander Suvorov conducted his brilliant Italian and Swiss campaigns, while at sea, Fyodor Ushakov’s navy hunted the French in the Mediterranean.

Vladimir Borovikovsky/Tretyakov State Gallery

However, as time passed, Emperor Paul I became increasingly convinced that the confrontation with the French was yielding no benefit for Russia at all. While the tsar’s troops were spilling blood and guts, the British and Austrians remained in the shadows, lapping up the spoils of Russia’s hard-fought victories.

The last straw was Britain’s seizure of Malta in 1800. Having dislodged the French garrison from the island, not only did the British not return it to the order of the Knights of Malta, but set about turning it into a colony and naval base. Paul, who happened to be Grand Master of the order, took this as a personal insult.

Friendship with Napoleon

Paul severed allied relations with the British and sought rapprochement with his former adversary France, who responded favorably.

The first consul of the French Republic, Napoleon Bonaparte, freed 6,000 captured Russian soldiers, sending them home in style as part of a full parade with banners and weapons waving. This gesture was highly appreciated by the Russian emperor. To show his gratitude, he even expelled the future Louis XVIII, who had been granted asylum in Russia after the French Revolution.

Jacques-Louis David/National Gallery of Art

The parties agreed to team up against Britain, which they believed to be the source of all trouble and unrest in Europe. “Together with your sovereign, we will change the face of the world!” Napoleon told the Russian envoy in Paris.

A sea invasion of Albion was immediately ruled out—even a combined Russian-French fleet had little chance against the “Mistress of the Seas.”

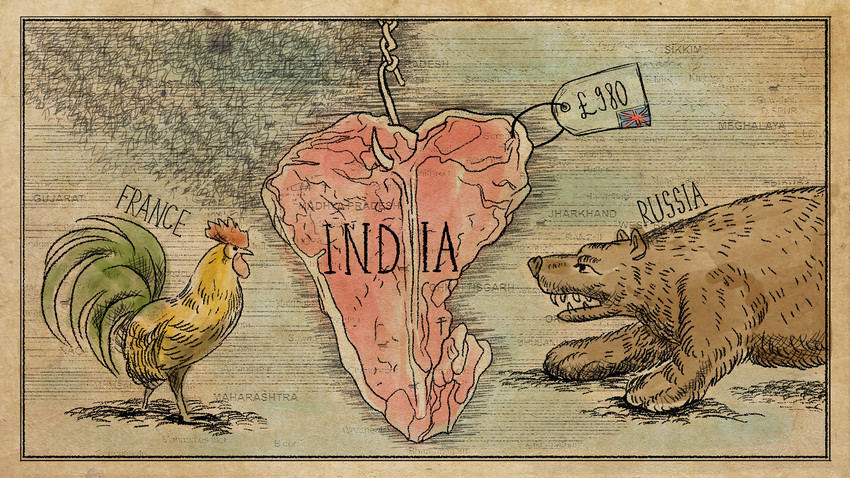

So Napoleon came up with a plan for a joint strike against the jewel in Britain’s imperial crown, India, which he had dreamed of conquering since the days of his Egyptian campaign.

Invasion plans

Under the plan, a French contingent of 35,000 soldiers, accompanied by light artillery, would march to Astrakhan, where they were to be joined by the 35th Russian army (15,000 infantry, 10,000 cavalry, and 10,000 Cossacks).

The combined Russian-French force would then be transported from Astrakhan across the Caspian Sea to Persian-ruled Astrabad (present-day Gorgan). The entire first stage of the campaign—from the French border all the way to Persia — was scheduled to last 80 days.

During the second 50-day phase, the joint force would march from Astrabad to Herat, Farah, and Kandahar in Afghanistan, and enter the territory of modern-day Pakistan from the north, before moving deeper into the Indian subcontinent.

Getty Images

Alongside the 70,000-strong Russian-French army, the Russian Far Eastern flotilla and a separate Cossack detachment were set to participate, the latter being the only part of the entire force that actually managed to advance on India.

At the personal suggestion of Paul I, the expedition was to be headed by the French commander General (from 1804, Marshal) André Masséna.

Orient express

The march of Ataman Matvey Platov’s Cossack troops was the first phase of the joint operation. It was not, as is commonly thought, a spontaneous decision by the emperor, but prepared long and carefully in advance.

On March 13 [O.S. Feb. 28], 1801, the Cossacks moved from the Don in the direction of Orenburg, from where they intended to surge through the Kazakh steppes, the Khanate of Khiva, and the Emirate of Bukhara (today’s Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan), and having pushed through Afghanistan, to enter the territory of present-day Pakistan.

Contrary to widespread belief, this route was far from terra incognita for the Cossacks. Russian diplomacy had taken care to establish friendly relations with the nomads of the Kazakh steppes.

Aleksander Orłowski/State Historical Museum

Suspecting that the Khiva and Bukhara rulers might be less welcoming to the Cossacks, Russia had wisely established allied relations with their neighbor, Tashkent State, which was ready to supply provisions and guides to Afghanistan.

Partition of India, perhaps

At the time of the Indian campaign, the British possessions in India were not exactly rock-solid. The East India Company, which was still colonizing the region, controlled only the eastern and southern territories of the peninsula.

With a good run of the dice, the Cossack units would reach the Sikh-dominated Punjab, followed by the largest state entity in Hindustan—the Maratha Empire. Both had resisted British expansionism for many years, and could be expected to take if not an amicable, then at least a well-disposed neutral stance on the new kid in town.

The British troops scattered across the East India Company’s possessions numbered around the same as the Cossacks—slightly more than 22,000, not counting the weak militia forces mobilized from the local population.

William Heath/National Army Museum

But against the Cossacks and Platov and Masséna’s 70,000-strong corps combined, they had little chance. What’s more, Paul and Napoleon were expecting to raise their troop levels through recruiting volunteers liberated from British oppression.

After crushing the East India Company, the arrangement was that the French would consolidate the southern part of the peninsula, while the Russians would set up shop in the north.

Operation aborted

However, the invasion was fated never to take place. On March 23 [O.S. March 11], 1801, Paul I was murdered as a result of court intrigue, in which Britain played an active role. One of the first decrees of the new emperor, Alexander I, was to order Platov’s Cossacks to return home.

Napoleon reacted furiously to the death of his Russian ally: “They missed me on the third of Nivôse [the fourth month of the French Republican Calendar and a reference to an attempt on Napoleon’s life on Dec. 24, 1800, in which the British were again implicated], but got me in St Petersburg.”

Public domain

Events went on to do an about-face. Just a few years later, Russia rejoined the anti-French coalition and suffered a string of bitter defeats before finally taking Paris.

As for the British, over the coming decades they crushed the states of the Marathas and the Sikhs, securing dominance in India until the mid-20th century.

Read about the Indian campaign of Alexander the Great and how a Russian spy outfoxed the British in 19th century Afghanistan.