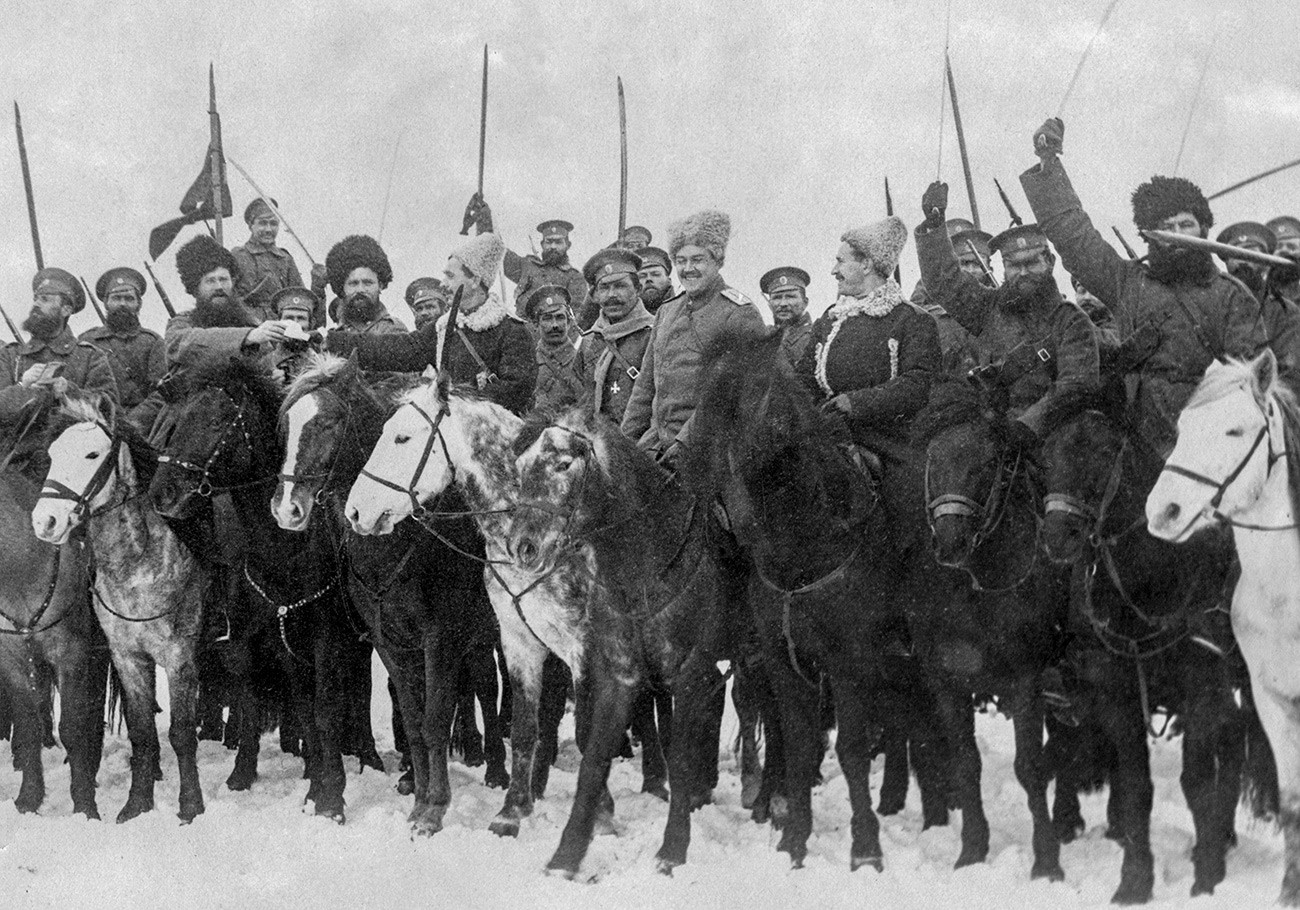

For centuries, the Cossacks were both a boon and a bane for Russia’s rulers. In exchange for limited autonomy, this “military estate” (as per the terminology of the day), formed as a result of the mixing of different ethnic groups, protected the frontiers of the Russian state against incursion.

Being excellent horsemen, they terrified the enemy on the battlefield, efficiently dispersed demonstrators from city squares, and served in the tsar’s personal guard. Yet the freedom-loving Cossacks were highly sensitive to any violation of their rights and way of life, so the government always needed a special approach in its dealings with them.

The collapse of the Russian Empire and the Civil War split the Cossacks painfully down the middle, placing them on opposite sides of the barricades. There were numerous violent clashes between the Red Cossacks and their White brethren in the vast expanses of southern Russia.

Nonetheless, the brutal “de-Cossackization” and land redistribution pursued by the Bolsheviks forced most Cossacks to side with the White movement. After the Red victory, the Soviet government set about settling scores. Its policy was aimed at erasing the very word “Cossack” from the Russian language. They lost their self-government and were subjected to repression and forced resettlement. As representatives of the “exploitative classes,” they lost the right to serve in the Red Army (with the exception of the Red Cossacks).

The worsening international situation and impending war in the late 1930s forced the Soviet leadership to revise its policy in relation to the Cossacks. A pro-Cossack campaign was launched with the aim of making Soviet Cossacks a mainstay of the regime. The state’s attitude to them suddenly thawed, and it began to support the revival of Cossack ways and traditions, encouraging them to take an active part in the country’s social and economic life.

The most important change was the lifting, in 1936, of the ban on Cossacks serving in the Red Army. Some cavalry units were redesignated as Cossack. In addition, Cossack divisions and corps were created from scratch, in which soldiers were permitted to wear traditional clothes. The very next year, the Cossacks participated in a parade on Red Square in full-dress uniform.

Cossack cavalry divisions took part in all the major battles of WWII in Eastern Europe. The cavalrymen, armed with sabers and rifles, were supported by 45mm and 76mm guns from other units. Since they could not fight on equal terms with the German tanks, they were used for counterattacks, breakthroughs, and lightning raids, when speed over rough terrain was the order of the day. In 1943, the fighting capacity of the cavalry corps was significantly beefed up when they received anti-tank artillery and air defense support.

For their heroism, the Cossack units were assigned “guard” status on several occasions. For instance, the 3rd Guards Cavalry Division, largely made up of Kuban Cossacks, became one of the most legendary formations in the Red Army. From July 1941 to May 1945, it crossed 12,700 km through the USSR, Poland, and Germany, engaging the enemy along the way, and participated in the battles for Moscow, Warsaw, and Berlin.

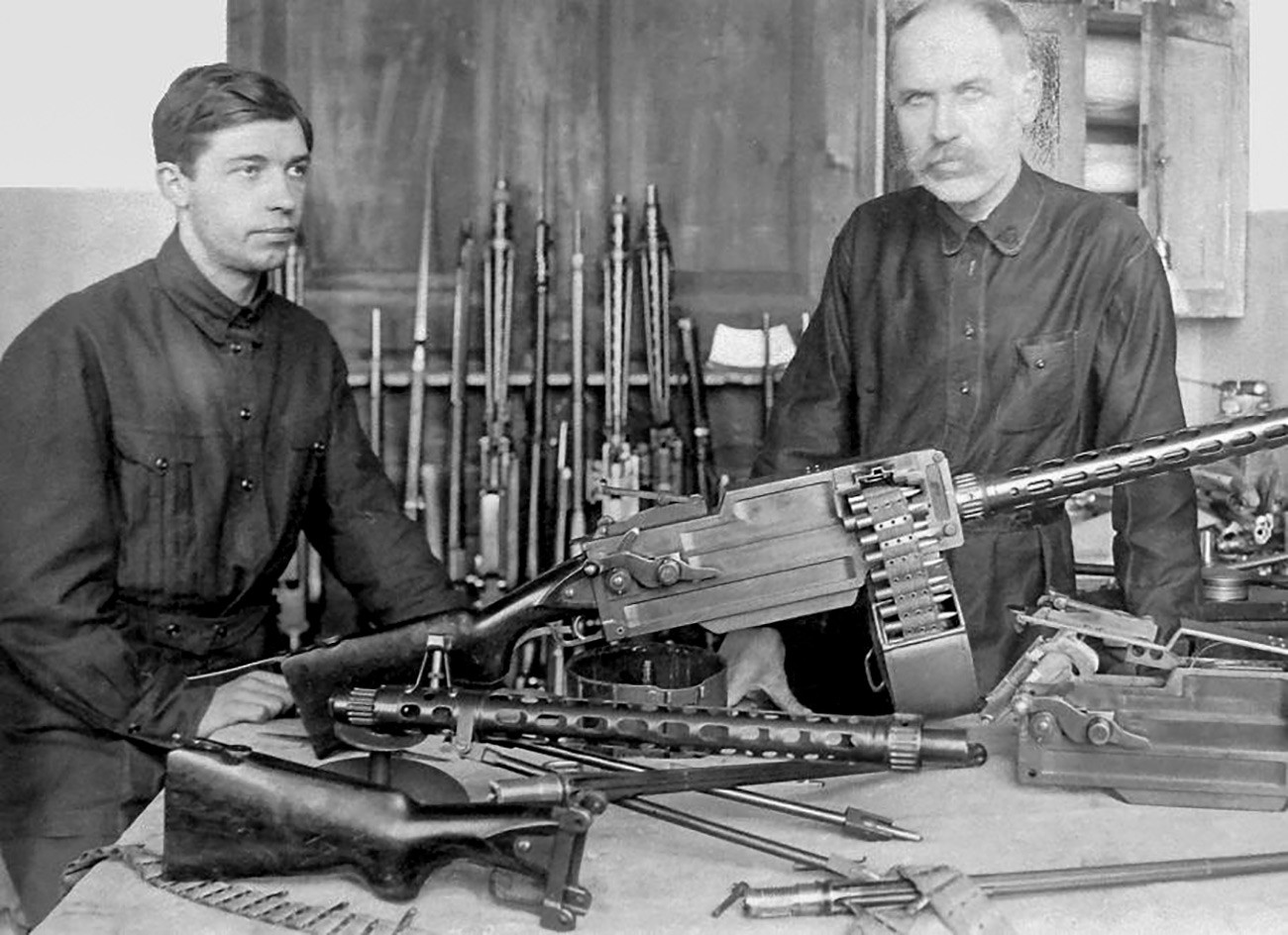

However, not all Cossacks who fought in the Great Patriotic War were cavalrymen. For instance, the 9th Krasnodar Plastun [Infantry] Division fought on foot and were nicknamed “Stalin’s cutthroats” by the Germans for their suicidal courage. The Cossacks also produced the top Soviet tank ace Dmitry Lavrinenko (52 kills), as well as small arms designer Fyodor Tokarev, creator of the famous TT pistol and the Red Army’s main rifle, the SVT.

Fedor Tokarev with his son.

Public DomainWhile most Cossacks defended their homeland, some were not prepared to bury the hatchet with the Soviet authorities. Thirsting to get even with the Bolsheviks and dreaming of political independence, some Cossacks joined the German side. Cossack units were set up in the occupied lands of the Kuban and Don, tasked with fighting partisans, maintaining discipline, and guarding captured Red Army soldiers.

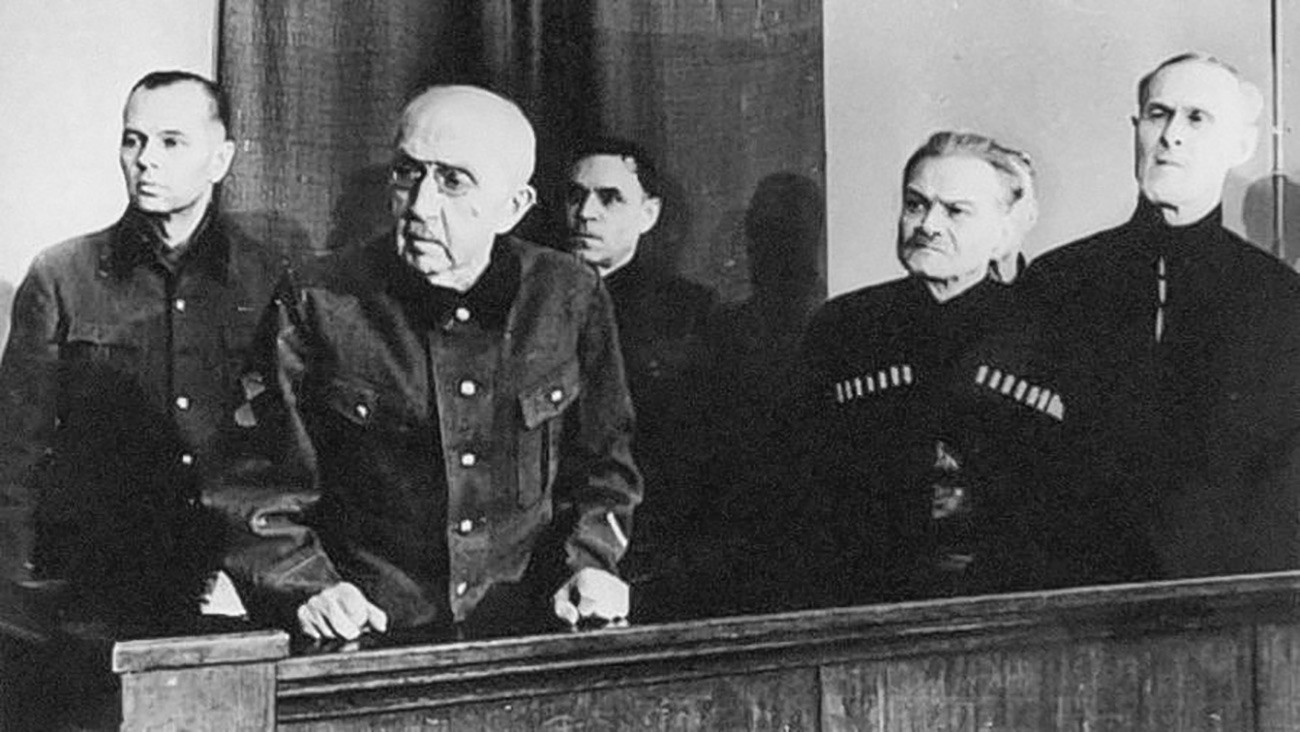

Together with the advancing Wehrmacht, the former Cossack leaders who had been forced to leave the country after their defeat in the Civil War returned to Russia. One of them, Pyotr Krasnov, made this appeal on June 22, 1941, day one of Operation Barbarossa: “I say to all Cossacks that this war is not against Russia, but against the communists, the Jews, and their sidekicks who are selling Russian blood. May the Lord help the German army and Hitler!”

Pyotr Krasnov.

Public DomainThe Fuhrer, for his part, favored the creation of collaborationist Cossack organizations (such as the Kosakenlager) and military units, since in Nazi ideology Cossacks were considered descendants of the Ostrogoths, and hence Aryans. This was bolstered by the fact that anti-Bolshevik Cossack émigrés in Germany had supported the Nazi Party even before it came to power.

The Cossack units of the Wehrmacht and the SS were not always made up exclusively of Cossacks. For instance, one of the most significant such formations — the 15th Cossack Cavalry Corps under the SS, which was 22,000-strong by the end of the war — consisted, in addition to Cossacks, of Soviet prisoners of war who had agreed to fight for Germany, as well as almost 5,000 German soldiers.

The Germans mostly used the Cossacks in their rearguard in Yugoslavia, where they fought against local partisans and the People's Liberation Army of Yugoslavia. When defeat was inevitable, the remnants of the Cossack formations broke through the Alps to escape the advancing Red Army, and surrendered to the British.

On May 28, 1945, around 50,000 Cossack collaborators, including refugees from Cossack regions, were handed over by the British to Soviet troops. Under the agreements of the Yalta Conference, the British were obliged to turn over all Soviet citizens who had fought against their own country. However, they went one further, handing over to Moscow many Cossack émigrés who were not Soviet citizens and could not, therefore, be considered “traitors to the Motherland.” As a result, the leaders of the Cossack collaborationist movement were executed, and the rest were sent to the camps. Those that survived were released in 1955.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox