In June 1940, German troops routed the French army and put a conclusive end to the Third Republic. Although the country pulled out of the war, not all French laid down their arms.

The nation was divided. Some were desperate to liberate their homeland, while others grew accustomed to the new Nazi-dominated Europe. Across practically the whole world, de Gaulle’s “Free France” (renamed “Fighting France” in July 1942) fought against the collaborationist Vichy regime. Their confrontation also spread to cold, distant Russia.

Hitler met with Philippe Pétain at Montoire-sur-le-Loir. October 24, 1940.

Bundesarchiv“This war is our war, we will see it through to the end, to victory,” commented the leader of the fascist French Popular Party, Jacques Doriot, on the German invasion of the Soviet Union in the summer of 1941 (Oleg Beida, The French Legion in the Service of Hitler. 1941-1944, 2013). It was collaborationist organizations operating in occupied France, as well as the Vichy puppet regime, that called for French troops to be sent the Eastern Front.

Unsurprisingly, Hitler was initially skeptical. He didn’t see the point of it for one thing, since the campaign against the Bolsheviks would surely last no more than five months… Besides, he didn’t want to give his defeated enemy a chance to improve its geopolitical standing, which is exactly what the Vichy government had in mind: French involvement in the “European struggle against communism” would ensure its preferential treatment in post-war Europe.

Jacques Doriot.

Getty ImagesIn the end, sending a military unit of French volunteers to the Soviet-German front was considered a good propaganda move. And by summer 1941, recruiting stations had opened where those wishing to “defend civilization against eastern barbarism” could sign up.

Unlike neighboring Spain, which had managed to raise a full-fledged division of 18,000 volunteers, the recruitment process in France was sluggish. Whereas many nationalist Spaniards were eager to get even with the Bolsheviks for the latter’s involvement in the Spanish Civil War, the French saw no particular reason to go anywhere near the far-flung, hostile Soviet Union.

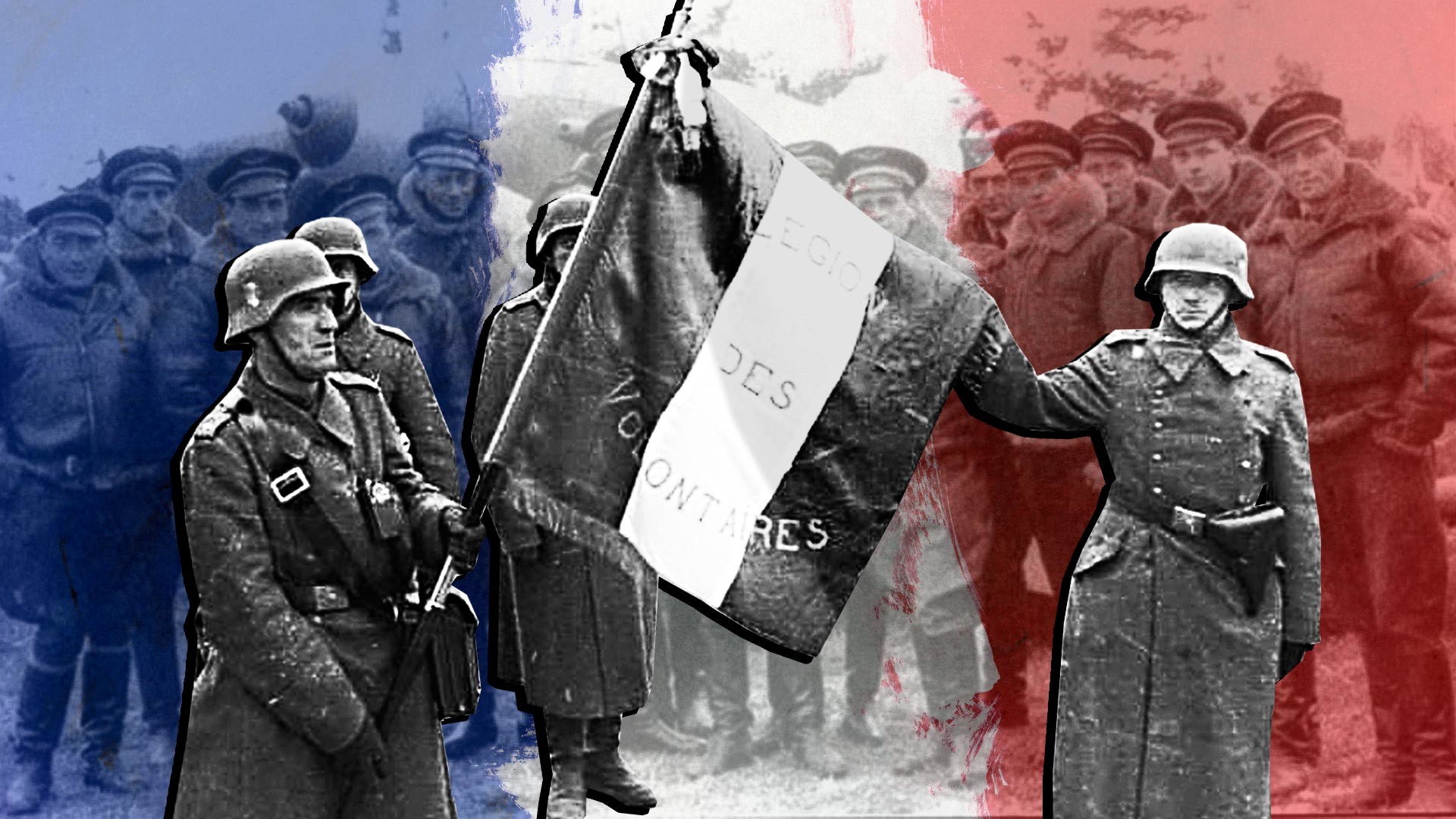

During its entire existence, the Légion des volontaires français contre le bolchevisme (Legion of French Volunteers against Bolshevism) attracted no more than 7,000 members, and the first unit had only 2,352 people.

After arriving at the Borgnis-Desbordes barracks near Versailles, the legionnaires had their first disappointment. Instead of the hoped-for French uniform, they were issued with the Feldgrau (“field gray”) — the standard uniform of the Wehrmacht. Only chevrons bearing the tricolor revealed their Frenchness. Having become part of the German army as the 638th Infantry Regiment, the Legion was dispatched to the Eastern Front in the fall of 1941.

The French legionnaires were transferred to Moscow at the height of Operation Typhoon, and made it closer to the Soviet capital than any other German allies (Romanians, Hungarians, Croats, Italians, Slovaks, and others) — just 63 km from the Kremlin. The French, as the Marseille-based newspaper L’Oeuvre put it, had “come to crush the monstrosity.”

German and Vichy propaganda repeated relentlessly that the legionnaires were the heirs of Napoleon’s Grande Armée, destined to restore the honor and glory of their ancestors. The French even organized field trips to Borodino, the site of the legendary battle of 1812.

But the 638th Infantry Regiment resembled Napoleon’s soldiers in a different way. Together with other sections of the invading Army Group Center, it faced a powerful Soviet counterattack, resulting in the loss of 500 men, including from frostbite and disease during its hasty retreat. Although not on a Napoleonic scale, it was a major blow to such a small formation.

The remaining legionnaires were withdrawn to Smolensk, and later used to carry out anti-partisan operations in the forests of Belarus. After a second unsuccessful clash with the advancing Red Army in 1944, the Legion was finally recalled from the front and disbanded. Many soldiers were transferred to the new 33rd Waffen Grenadier Division of the SS Charlemagne and took part in the defense of the Führerbunker — Hitler's last refuge in Berlin.

Soviet infantry during the Battle of Moscow.

Arkafy Shaikhet/SputnikNot all French on the Eastern Front were there as volunteers. More than 100,000 inhabitants of the disputed region of Alsace-Lorraine (long contested by France and Germany, and annexed by the Third Reich in 1940) were classified as pure-blooded Germans and mobilized for action. However, this Germanization occurred only in 1942, when the war with the USSR started to demand ever more human resources.

Most French-speaking Alsatians and Lorrainians gravitated towards France and were highly reluctant to fight for Hitler. Referred to as the Malgré-nous (“Against our will”), they were distributed in small groups among the German units and packed off to the Eastern Front far from home.

“We came across some interesting types,” recalled Senior Lieutenant Roman Glok of the Soviet 180th Heavy Artillery Brigade: “We enter a village, there’s a woman standing outside a hut, she invites us inside. We go in, there’s a German in uniform sat at the table. The woman says, ‘he’s a Frenchman.’ We check his documents and, sure thing, he’s French. We ask him to sing the French national anthem, and it sounds real enough. In the end, we don’t even take him prisoner.”

While the Vichy government was looking to ingratiate itself with Hitler, their Free French opponents were wondering how to stop the eastern crusade. “Anyone who fights against Germany is fighting to liberate France,” stated Charles de Gaulle on the day of the Nazi invasion of the USSR. (Sergey Dybov, The True Story of the Normandie-Niemen Fighter Regiment, 2017)

Charles de Gaulle in Tunisia in 1943.

Marjory CollinsThe Gaullists were severely limited in their options. Unable to fight the collaborators in Europe, they sought to wrest control of France’s overseas colonies from the Vichy hands. But in some places, they were not greeted as liberators. Many French despised de Gaulle for collaborating with the British, who they believed had abandoned the French army at Dunkirk and treacherously attacked the French fleet in the Algerian port of Mers El Kebir to prevent its surrender to the Germans, costing the lives of nearly 1,300 French sailors.

The leader of the Free French was in many respects burdened by British assistance, which gave him and his people no room for maneuver. The deployment of French troops to the Soviet Union was an opportunity to cast off at least some of this dependency, and establish long-term ties with a new ally.

French pilots of the "Normandie-Niemen" air regiment.

Getty ImagesThe original idea was to send a French mechanized division, then stationed in Syria, to the Eastern Front. However, due to the complexity of the operation, it was decided to set up a fighter aviation group in the Soviet Union. In late 1942, groups of French volunteer pilots began arriving in the USSR to serve in the new Normandie squadron (later regiment).

Wanting to distance themselves from the British, the French asked to be provided with Soviet aircraft, despite the availability of Hurricane fighters supplied to Moscow by London.

The French pilots, it has to be said, were extremely satisfied with the quality of the Yak-1 aircraft. “It was lighter than the Spitfire, and seemed faster and easier to fly. It takes off quickly and is very maneuverable... it’s ideally suited to snow, dirt, and the endless Russian fields,” wrote pilot Roland de la Poype in his memoirs L'épopée du Normandie-Niémen (“The Epic of Normandie-Niemen”).

Subsequently, the Yak-1 was replaced by less maneuverable, but faster and better-armed Yak-9. The pilots ended the war aboard Yak-3 fighters.

The Normandie pilots flew in their French uniforms (such liberties were not permitted in the British Royal Air Force), and with the French flag on their planes. The Soviet command hardly intervened at all in the regiment’s internal affairs — another welcome change from the British approach.

The Soviet authorities even went so far as to allow Russian volunteers — the children of White Russian émigrés in France, the Bolsheviks’ opponents in the Russian Civil War — to join the regiment. As Soviet diplomat Alexander Bogomolov remarked to one such pilot Konstantin Feldzer: “If you or the French pilots suddenly decide to restore the tsar to the throne, it won’t be a problem for us, because 100 million Russians don’t want it.”

Jacques Andre.

Archive photoAs the French overseas territories passed from the Vichy regime to the now Fighting French authorities, former collaborator pilots began to arrive in the Soviet Union. There were more than a few scuffles and contretemps between them and the non-Vichy pilots, But over time, the “Vichyists” managed to atone for their past, and one of them, Jacques Andre, even became a Hero of the USSR.

The tour of duty of the Normandie regiment (which added “Niemen” to its name in 1944 as part of the Soviet 1st Air Army) included some of the key battles of the war: Kursk, Operation Bagration, which ended in the defeat of Army Group Center, and operations in East Prussia.

The Soviet command highly rated the skills of the French pilots, but criticized their excessive individualism. More than once, they broke formation to go on personal seek-and-destroy missions. Thinking they were pursuing a lone enemy aircraft, they often ran up against an entire group of German fighters and got shot down. What’s more, because the Normandie-Nieman pilots had been declared traitors by the Vichy government, they were subject to immediate execution when captured.

Normandie-Nieman fought not only in the air, but on the ground, too. It was common practice for French pilots to patrol the forests of Belarus and Lithuania in search of enemy units. Although the French generally treated prisoners better than the Soviets did, military interpreter Igor Eichenbaum recalls that when they stumbled upon a group of French volunteers in the Wehrmacht, they executed them on the spot.

Despite the fact that de Gaulle’s troops were now involved in liberating France together with US and British forces in 1944, it was decided to leave Normandie-Niemen on the Eastern Front. Only in June 1945 was the air regiment ordered back to its homeland.

The French pilots flew home aboard their Yak-3 aircraft, a “modest gift from the Soviet Union to French aviation.” It was these fighters that would spur the revival of the French Air Force.

With the loss of 42 pilots, Normandie-Niemen had scored 273 enemy kills, accounting for 80% of all Fighting French aerial victories during the entire war.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox