In addition to school, many Soviet children attended hobby groups. These were partly about having fun outside of school, but they also helped children decide what they wanted to do in life.

Lliterature classes, Taganrog, 1960.

Issak Tunkel/MAMM/MDFThe first of these hobby clubs started in Moscow and then other Soviet cities in the early 1920s. They were called "houses of pioneers" or "palaces of pioneers." In a sense, they actually were real palaces converted from former merchants’ mansions that were expropriated after the 1917 Bolshevik revolution. The palaces of pioneers were described by Soviet magazines as "laboratories for bringing up a new breed of cultured citizens of the socialist homeland.”

Moscow House of Pioneers.

mos.ruBefore the war only large cities such as Kharkov, Leningrad, Kiev and Taganrog had houses and palaces of pioneers, but in the 1950s a full-on construction boom began across the country. Within a few years, over 2,000 houses of pioneers were built, and by the end of the 1980s there were already 3,800! And each one of these had dozens of different clubs.

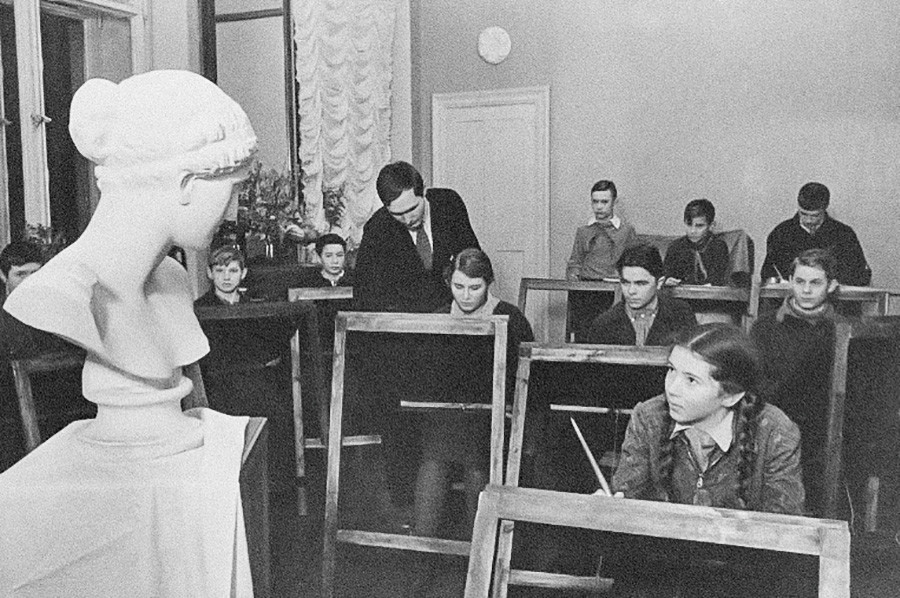

Leningrad Palace of Pioneers, 1950s.

Vladislav Mikosha/MAMM/MDFOne of the biggest was the Moscow House of Pioneers, which opened in the Chistyye Prudy neighborhood in 1936 (although it later moved to Vorobyovy Gory in the 1960s). Just a year later it hosted more than 170 clubs that were attended by 3,000 childs. Some of these kids went on to become famous film directors, including Alexander Mitta, Stanislav Rostotsky and Rolan Bykov. Participants in these clubs could, among many other things, learn how to draw, dance or study literature. Prominent writers of the time such as Agniya Barto, Korney Chukovsky and Samuil Marshak would come to meet the pioneers.

Drawing classes at the Moscow House of Pioneers, 1930s.

Mark Markov-Grinberg/MAMM/MDFMuch attention was devoted to the technical workshops. In just about every Soviet city, children could join young inventors’ clubs and groups specializing in aircraft modelling, rail and water transport, communications, photography or cinema.

Aircraft modelling classes, Dushanbe, 1982.

Yuri Nabatov, Robert Netelev/TASSThere was no division by gender, but girls joined needlework clubs and ballet and theater workshops more often than engineering groups. Pokerwork and carpentry classes were more popular with the boys, although sometimes it was the other way around.

Needlework club, Murom, 1952.

Vasily Ulitin/Murom Historical Art MuseumTeenagers who were passionate about cars could not just learn about vehicle design but also drive them on their own. Some houses of pioneers even had karting and motocross tracks.

At the karting classes, Kuybyshev (today Samara), 1988.

V.Muradov/TASSAnd if there were young motorists, then of course there had to be clubs for young traffic inspectors as well! They wore dark blue uniforms for classes and studied road safety.

Young road policemen in Tbilisi, 1974.

Givi Kikvadze, Anatoly Rukhadze/TASSThere were also countless sports clubs for children, including many with a military and patriotic slant. In addition to sports schools, there were clubs for young snipers, parachutists, signal operators and dog handlers, as well as navigation and tourist clubs. And these weren’t about learning how to book a hotel. Instead, kids were taken on hikes and treks and went rafting down rivers.

Shooting gallery for youth at the Moscow House of Pioneers, 1952.

Valentin KhukhlaevAnd after Yuri Gagarin's famous journey into space, young cosmonaut clubs showed up in different Soviet cities. In these, teenagers studied the theoretical aspects of rocket design and the history of space exploration, but they also underwent flight training on flight simulators.

Young cosmonauts classes, Moscow, 1970.

Valentin Kuzmin/TASSAfter the collapse of the USSR, most of the clubs either became private institutions or closed down entirely. But some technical workshops are still available in Russia free of charge. For example, children's railways can still be found, as well as cosmonaut clubs at space centers.

Children railway outside Moscow.

Kirill Zykov/Moskva AgencyIf using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox