In late summer 1941, the Soviet Navy witnessed some of the darkest days in its history. On August 28, practically in front of the eyes of the German troops who had seized Tallinn, the Red Banner Baltic Fleet set sail from the capital of Soviet Estonia in the hope of reaching Leningrad. The so-called ‘Tallinn Crossing’ ended with the loss of over 50 ships and took the lives of more than 10,000 Soviet soldiers, sailors and civilians.

Tallinn became the main base of the Soviet Baltic Fleet shortly after the Baltic states became part of the USSR in 1940. The city was well prepared to repel attacks from the sea and from the air. The weak link in its defense were fortifications on land since no one could imagine that an enemy would be able to pass through Lithuania and Latvia and reach the capital of Estonia.

The Port of Tallinn on 1 September 1941 after having been seized by the Germans.

BundesarchivHowever, this is exactly what happened. Already in early July, the troops of Hitler’s Army Group North entered Estonian territory, and on August 7 they reached the coast of the Gulf of Finland, thereby cutting off the city by land from the main forces of the Red Army. Even in that situation, the Soviet command did not give an order to evacuate Tallinn, intending to defend it to the last. The city's defense force was very small and only consisted of units of the 10th Rifle Corps, sailors, the NKVD and local self-defense.

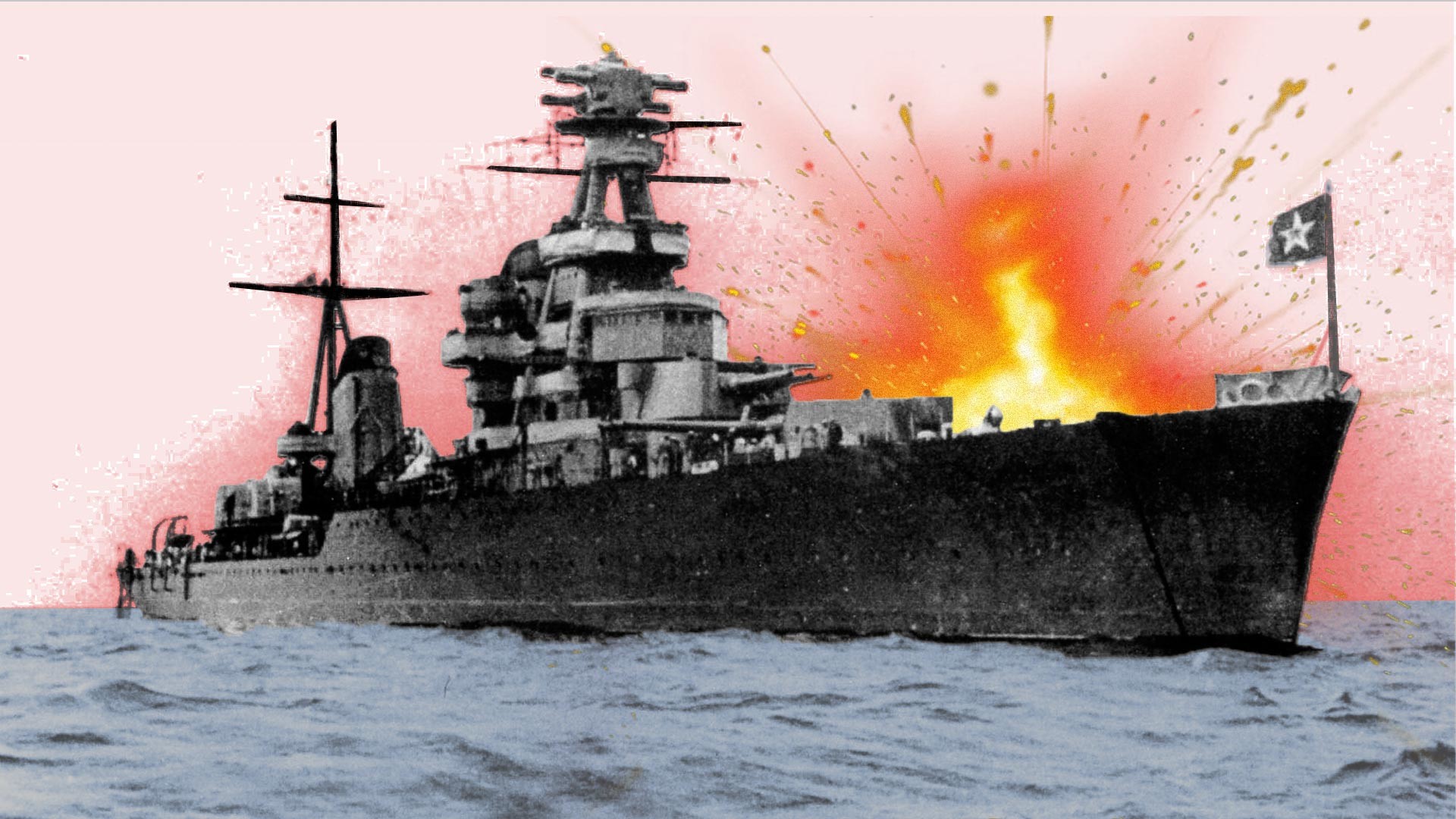

On August 25, the situation became critical — Soviet troops had been pushed back to the main defensive line in the vicinity of Tallinn, and German artillery could reach the entire city and the port with its shells. One advantage, however, was that the Baltic Fleet ships could also now pound the enemy. This fire support was very useful to troops covering the long-awaited evacuation of the Baltic Fleet that was announced by its commander, Vice-Admiral Vladimir Tributs, on August 27.

The boarding of the ships lasted all through the day and night that followed, and took place in an atmosphere of complete chaos and without any system in place. Things were further exacerbated by panic as fighting was already taking place on city streets.

Vice-Admiral Vladimir Tributs.

Archive photoThe ships were overloaded, and there was not enough space onboard for many soldiers and sailors, who were running up and down the pier. Evacuation of military hardware was not even an option: the machinery was simply thrown into the sea or blown up. Many of the Red Army units fighting the enemy in the city streets also did not get on board. When the Germans occupied Tallinn, they captured about 11,000 Soviet soldiers.

On August 28, the 225 ships of the Baltic Fleet in four convoys left Tallinn and headed for the Kronstadt naval base on Kotlin Island near Leningrad. According to various estimates, they had from 20,000 to 41,000 people on board, including servicemen of the 10th Corps, civilians and the leadership of Soviet Estonia.

Baltic Fleet commanders were well aware that since July, the Germans and the Finns had been busy mining the Gulf of Finland, but they did nothing to rectify the situation. In the end, the minefields through which the Soviet ships had to pass became the main cause of the tragedy.

The convoys moved extremely slowly, in the wake of minesweepers, whose task was to detect and destroy mines. Often, the Soviet ships, coming under fire from the enemy's coastal artillery or being attacked by Finnish torpedo boats (German ships were not involved in the fighting), would leave the narrow strip that had been cleared of mines, hit a mine and sink literally in a matter of minutes.

The slow-moving mass of ships became an excellent target for Luftwaffe aircraft, which fired as if conducting a target practice. And even if the German pilots failed to sink a ship themselves, the vessel, having been damaged, often went off course and hit the mines.

There was no Soviet aviation in the sky. The belated evacuation was carried out when all the runways near Tallinn had long been lost to the enemy. Fighters could provide cover for the convoys only at the final stage of the voyage. As the sailors bitterly joked: "We made the journey from Tallinn to Kronstadt under the cover of German dive bombers."

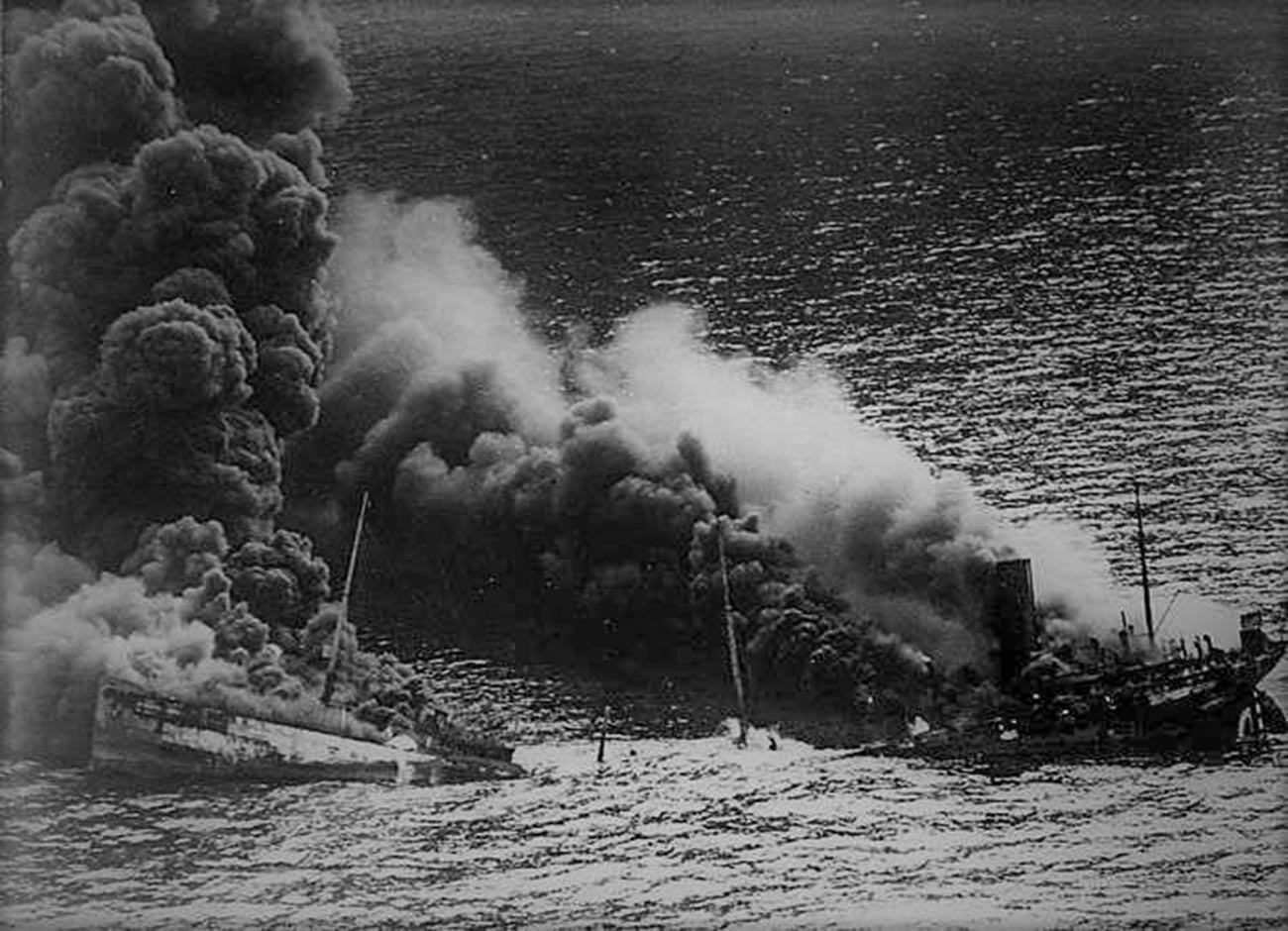

The fleet's command lost control of the operation almost immediately after leaving Tallinn. The ships acted at their own peril and continued to perish en masse from mines. The few minesweepers, which had to operate at night, themselves often hit mines and sank. The entire rearguard (five ships out of six), which had no minesweepers attached to it at all, was almost completely destroyed.

The losses were enormous. For example, out of 1,280 people on board the sunken transport ship, Alev, only six people survived. Deputy head of the special section in the 10th Rifle Corps Lieutenant of State Security Doronin reported that as the transport ship Veronia was sinking he had heard numerous revolver shots: people onboard were shooting themselves as they did not want to go under the water while still alive.

“Suddenly, a fiery black cloud rose over the middle of the ship. The flame rose to the tops of the masts, while the expanding column of black smoke and objects flying about and up rose twice as high as the flame,” recalled Vladimir Trifonov, a signalman from the Suur-Tyll icebreaker, when recounting the sinking of the destroyer Yakov Sverdlov.“ A few seconds later, when the smoke dissipated and fell behind the mortally wounded ship that was still moving by inertia, I clearly saw that the ship had been torn in half, its bow and stern began to bulge up, while parts of the torn hull began to sink under the water. Within no more than two minutes, the ship was gone."

Under constant attacks by German aircraft, the sailors, nevertheless, managed to rescue over 9,000 people from the water. It was only when, closer to Kronstadt, Soviet aviation appeared in the sky that the Baltic Fleet could feel relatively safe.

In the course of the three days that the Tallinn crossing took to complete, the Baltic Fleet lost from 50 to 62 ships, including destroyers, submarines, minesweepers, patrol boats, coast-guard boats, and torpedo boats. However, most of the lost ships (over 40) were transport and auxiliary vessels. For their part, the Germans lost 10 aircraft.

The operation led to the deaths of between 11,000 and 15,000 people. In addition to civilians, they included many soldiers of the 10th Rifle Corps and sailors, who had invaluable combat experience in fighting for Estonia.

Despite heavy losses, the Baltic Fleet managed to survive as a combat-ready unit. Having been through this terrible ordeal, it did not get much time to rest. Just a week later, heavy fighting for Leningrad began, in which the fleet was to play a significant part.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox