The American Revolutionary War was a stellar time for Scottish sailor John Paul Jones. Not only was he an officer of the Continental Navy, but one of the most successful.

Jones actively engaged in privateering off the coast of Britain, hunting for enemy merchant ships. He is also credited with pulling off one of the greatest American naval victories in the conflict: the capture of the British sloop Drake and the 50-gun frigate Serapis.

John Paul Jones.

Charles Willson Peale/Independence National Historical ParkWhen the war ended in 1783, “the father of the American Navy,” as Jones is often called, found himself out of work. He languished as a diplomat in Europe until 1787, when suddenly he was given the chance to return to sea. The Russian Empire, then at war with the Turks, was interested in his services.

Catherine the Great immediately promoted Jones to the rank of rear admiral (in the U.S. Navy he had been a mere captain), and sent him to the Black Sea under the command of His Serene Highness Prince Grigory Potemkin. “This man is very capable of multiplying the enemy’s fear and trepidation. His name, methinks, is known to you. When he comes to you, you shall better determine for yourself whether such rumor befits him,” the empress wrote to the Russian military leader.

Pavel Jones, as the American naval commander was renamed in the Russian manner, validated his reputation. Commanding a squadron of 11 ships, he, together with the oar-propelled flotilla of Rear Admiral Karl Nassau-Siegen, defeated the Turkish fleet in June 1788 near the Black Sea fortress of Ochakov. The enemy lost 15 ships, with 6,000 killed and 1,500 taken prisoner.

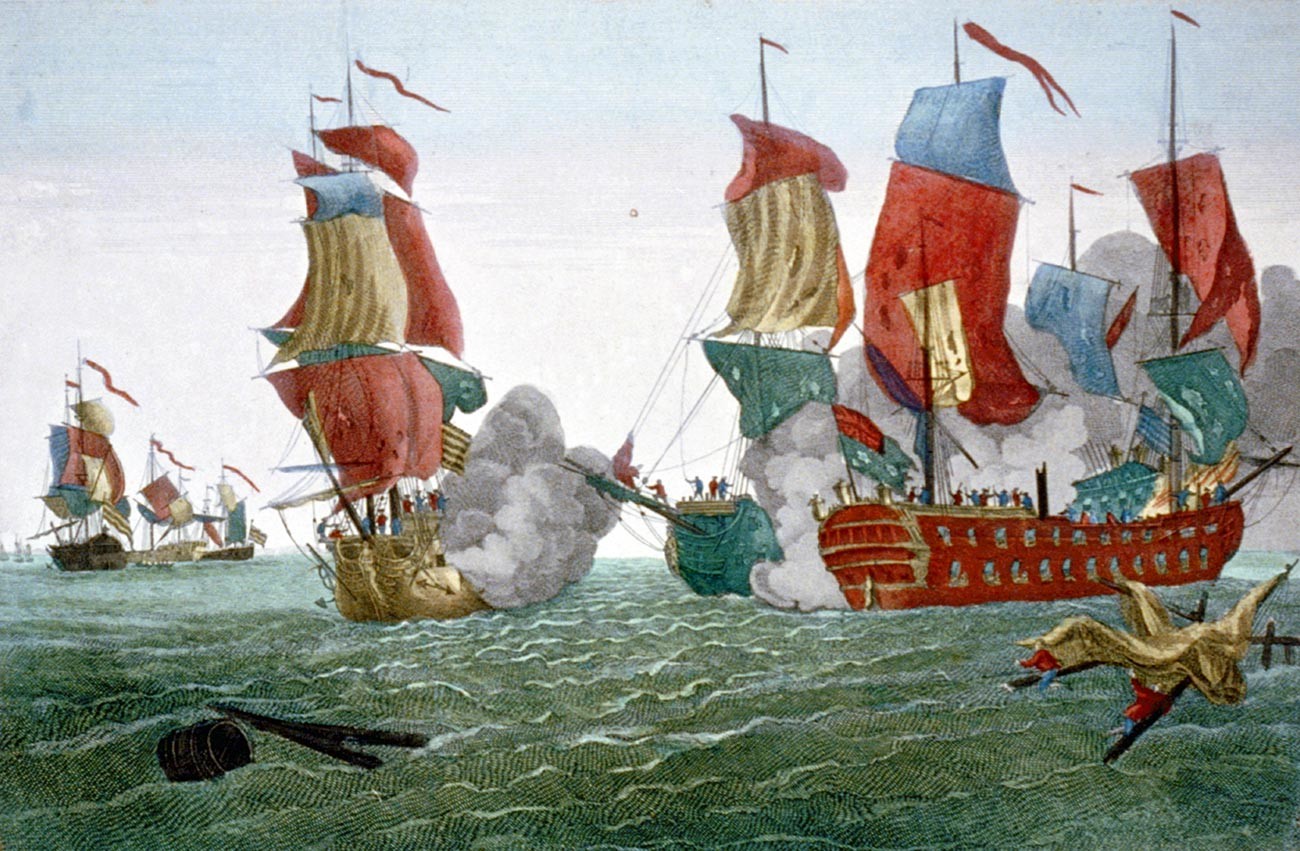

Battle of Flamborough Head, East Yorkshire, England, 22 Sept. 1779, between the American John Paul Jones and British vessel 'Serapis'. Print 1780.

Global Look PressJones had a far harder task forming personal relationships. His communication with Potemkin was terse and formal, while he and Nassau-Siegen, according to the prince’s adjutant Count Roger de Dame, “hated each other from the heart.”

As a result, even before the war was over, Pavel Jones was recalled to St. Petersburg under the pretext of being assigned to the Baltic Fleet. Instead, however, he had to endure one of the toughest ordeals of his life.

On March 31, 1789, the mother of ten-year-old Ekaterina Stepanova (Goltzwart) accused the rear admiral of raping her innocent daughter. The case was widely publicized and reached the empress herself.

Catherine the Great.

Fedor Rokotov/The State Tretyakov GalleryAlmost immediately, on April 2, Jones sent a message to the St. Petersburg chief of police, Nikita Ryleev, in which he argued that Stepanova was far from being a harmless simpleton, but “a fallen girl who visited my house several times and with whom I often frolicked, but always paid for it.”

However, the rear admiral soon changed his story. He told his friend, the French Ambassador, Count Louis Philippe de Ségur (the only one who had not renounced him in St. Petersburg society) that he had had no sexual relations with Stepanova, but was the victim of deceit on the part of her and her mother.

According to this new version of events, the girl had come to ask if he had any linen or lace that needed patching up, but he had none. “Then she started making obscene gestures. I advised her to stop this disgusting activity, gave her money and told her to leave,” Ségur retold Jones’ words: “As soon as she walked out of the door, she tore off her sleeves and lace kerchief, screamed ‘Rape!’ and threw herself into the arms of Mama Goltzwart, who suddenly happened to be there.”

His Serene Highness Prince Grigory Potemkin.

Johann Baptist von Lampi the ElderFinding himself at the center of a major scandal, the rear admiral fell into deep depression. Ségur even saved him from suicide, having found his friend at home with a loaded pistol in his hand.

In the course of the proceedings, however, it was established that the mother had lied about both the age of her daughter (she was in fact 12 years old — still considered an early but acceptable age for sexual activity in those days) and the rape: Stepanova had peacefully met Jones on repeated occasions. The American was sure that an ill-wisher in the highest circles of power was behind the scandal. His (or her) identity, however, remains unknown.

Despite the fact that all charges against John Paul Jones were dropped, he was still persona non grata in Russia. He never received his expected transfer to the Baltic Fleet, unlike his foe Nassau-Siegen, who might well have been the one who plotted against the rear admiral.

John Paul Jones.

Public DomainCatherine the Great granted the U.S. naval commander a two-year leave of absence with retention of rank and salary. He was in fact being discharged, and Pavel Jones refused to take it lying down.

Yet his numerous petitions to the authorities went unanswered. In August 1789, an angry and embittered John Paul Jones was forced to leave Russia for good.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox