On December 24, 1970, American TV networks broke the news from the USSR.

“Leningrad today handed down two death sentences in a case of attempted airplane hijacking. The first time apparently death penalties have ever been pronounced in a hijacking case,” said an anchor presenting the story on NBC.

The trial would cause an international backlash and soon thereafter, the Soviet Union would be forced to address its so-called “Jewish problem”.

The Six-Day War

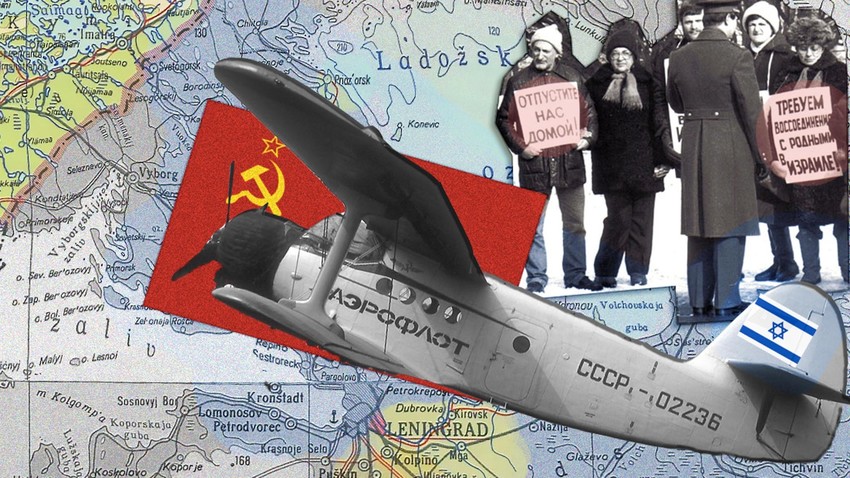

Back in the 1970s, migrating from the Soviet Union was an unattainable dream for many. To leave the Soviet Union for another country, it was necessary to obtain exit visas — a formal permission from the authorities to migrate. In practice, many people found it impossible to get. By the 1970s, the problem became so acute that a new term emerged to denote those who had been refused exit visas — Otkazniki (Eng.: Refuseniks).

Elena Keis/Aba Taratuta fund

Soviet Jews comprised a fair share of the Refuseniks. The Soviet pro-Arab position during the 1967 Six-Day War — an armed conflict between Israel and a coalition of Arab states — triggered social consolidation among the Soviet Jews.

“At that time, president of Egypt Abdel Nasser came to Moscow. He said bluntly that Israel is a ‘cancer on the world map’ and [that it] must be destroyed. None of the Soviet leaders contradicted him. It angered me to the core,” said Mark Dymshits, one of the conspirators of the 1970 hijacking.

Jews from all over the Soviet Union expressed their desire to return to their historic motherland, Israel, but the Soviet authorities had other plans, since a mass migration could have undermined internal stability and the USSR’s carefully constructed image abroad. Disenchanted by the system, a tiny group of Soviet Jews contemplated a daring escape from the USSR: they would hijack an airplane.

‘Operation Wedding’

On the morning of June 15, 1970, 16 Soviet Jews who had been refused exit visas showed up at the Smolny Airport near Leningrad. Posing as a group going to a wedding — hence the name of the operation — they were bound for a flight to Sortavala, a Soviet city near the Finnish border, with a landing in Priozersk, another Soviet city close to the border.

The plan, devised a year before the attempted hijacking, was quite straightforward. The hijackers would purposefully target a small airplane and book all the seats on it so there was no one unaffiliated with the group on board, except for the pilots. When the airplane landed in Priozersk, the hijackers would commandeer the aircraft and leave the pilots restricted, but unharmed on the landing strip, while one of the conspirators would take control of the airplane and direct it across the Finish border away from the USSR. When out of the USSR’s airspace, they would direct the plane to Sweden and, once there, surrender and publicly declare their desire to move to Israel.

“I had almost no doubt that we would be arrested. But, I thought that after serving my sentence, it would be easier for me to leave the Soviet Union,” said Eduard Kuznetsov, one of the conspirators.

Anat Zalmanson-Kuznetsov, 2016

Other members of the group did not seem to share Kuznetsov’s pessimistic expectations. Another conspirator portrayed the group as being extremely excited in anticipation of the risky, all-or-nothing kind of mission.

“Only people as intoxicated with excitement as we were could not understand that this [flight] was an obvious bait,” said Anatoly Altman, one of the hijackers. Altman referred to the all-too-convenient flight which magically showed up as the group of Soviet Jews was ready to make their move. Indeed, the flight was a setup by the KGB, who had intercepted the group’s communication and had been following them since then.

As the group approached the airplane on the runway, the KGB apprehended them before the plane could even take off.

“By the time I heard the shots, they had already grabbed me. I turned around and saw that Dymshits was bleeding all over his face,” said Yosef Mendelevich.

Anat Zalmanson-Kuznetsov, 2016

All 16 conspirators were arrested and stood trial shortly afterward. The trial that lasted from December 12 to 24, 1970, charged the defendants with “high treason”, “attempt to steal socialist property on large scale” and “anti-Soviet agitation and propaganda”, since the prosecutors reasoned the attempted hijacking cast a shadow on the USSR’s image in the world.

The verdict was harsh: most of the members of the group were sentenced to years in prison; Mark Dymshits and Eduard Kuznetsov — the leaders — were ordered to face a firing squad.

The fallout

The trial and the harsh sentences caused a worldwide backlash: people from various countries protested against the verdict and leaders of states appealed to the Soviet authorities for clemency.

Moshe Milner/National Photo Collection of Israel (CC BY-SA 3.0)

Perhaps, the protests were influenced by the narrative the defendants offered at the hearing. “Probably, for the first time in Soviet history, people did not ask for pardon, [but] stood their ground and openly declared that they wanted to leave the country,” said Eduard Kuznetsov. “We were forced into it. The ones who forced us to do it are the ones who are guilty.”

After the trial, the public view of the defendants as victims of the rigid Soviet system prevailed in the West. “The real defendants in the court were not the handful of accused, but the tens of thousands of Soviet Jews who have courageously demanded the right to emigrate to Israel,” wrote The Times’ editorial.

Public Domain

Succumbing to the growing pressure, the Soviet authorities commuted most of the sentences, most importantly substituting the two death penalties with 15 years in prison. Eventually, Dymshits and Kuznetsov were freed in a spy exchange between the U.S. and the USSR in 1979. Others were freed after they had served their sentences.

Since that moment, however, the so-called Jewish question in the USSR became an important aspect of bilateral relations with the U.S.

Anat Zalmanson-Kuznetsov, 2016

The plot to hijack the airplane, the trial that followed and the international backlash that it caused marked a tectonic shift in domestic Soviet policy. Within one year of the trial, more exit visas were granted to Soviet Jews than in the previous 10 years combined; and the following year — three times as many, amounting to 32,000 permissions to leave.

When the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991, tens of thousands of Jews migrated to Israel. Up to these days, descendants from the post-Soviet states form a hefty part of Israel’s total population.