Kuban Cossacks, 1979

Boris Ushmaikin/SputnikRussian Cossacks are an unusual cultural phenomenon. In their pure form, they are neither a social class nor an ethnic group, but, rather, an ethno-social community with its own characteristic features.

The etymology of the word ‘Cossack’ is not fully known. According to one theory, translated from Mongolian, it means “to guard a frontier” and the Cossacks were, indeed, a military formation that guarded the borders of the Russian Empire. According to another theory, it is a Turkic word for an “adventurer” or “free man”.

Kuban Cossacks, late 19th century

SputnikThis is how the Great Soviet Encyclopedia describes Cossacks and it is difficult to argue with this statement. Cossacks were always in the service of the state, but, at the same time, they were also freedom-loving people - hence the Cossack rebellions throughout history. The Cossacks Stepan Razin in the 17th century and Yemelyan Pugachev in the 18th initiated entire large-scale wars against tsarist troops.

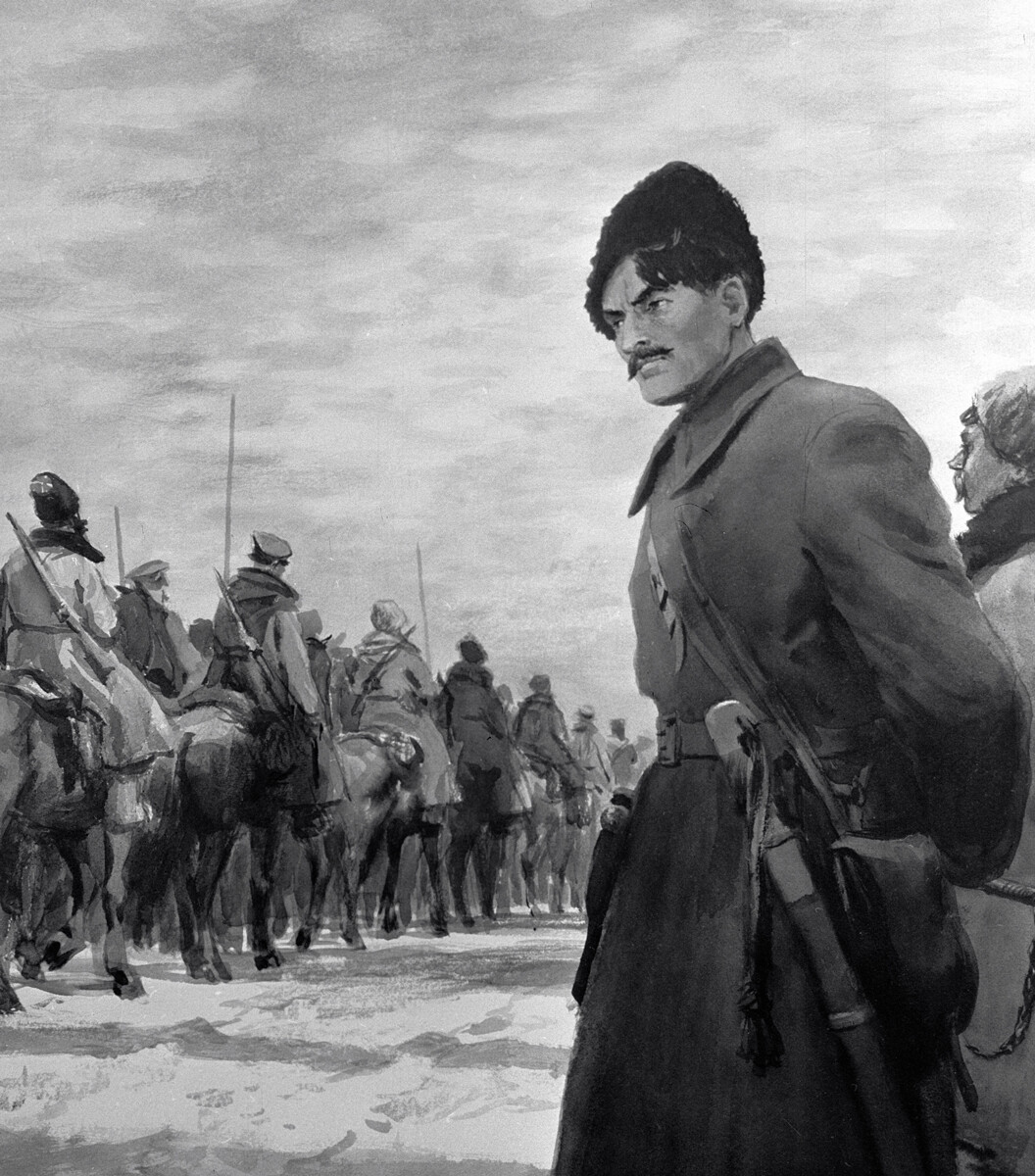

An illustration for Mikhail Sholokhov's novel 'And Quiet Flows the Don,' by the artist Orest Vereisky

SputnikDon, Kuban, Zaporozhian, Siberian and Ural Cossacks all “inhabited” various parts of the country and were very diverse in their ethnic composition, but they were still Cossacks. The first official Cossack army was actually formed on the River Don - in 1570, the Don Cossacks received an official document to this effect from Ivan the Terrible.

A still from 'And Quiet Flows the Don' movie, 1958 / Gorky Film Studio. Directed by Sergei Gerasimov

SputnikDuring the 1917 Revolution and the ensuing Civil War, the Cossacks were divided - some supported the “Red” Bolsheviks, while others took the side of the “White” monarchists. Many vacillated, however, crossing over from one side to the other, as masterfully depicted in Mikhail Sholokhov’s best-known novel ‘And Quiet Flows the Don’. Taking advantage of some Cossacks’ inclination for rebellion, Hitler lured several of their formations to his side during World War II.

The meeting of minor Cossacks' circle in the village of Vityazevo.

Alexei Boitsov/SputnikOriginally, Cossacks were supposedly formed from runaway peasants seeking freedom from the state or from their masters and from the oppression of feudal service. So, Cossack settlements enjoyed a system of self-government that was unique in Russia, known as volnitsa (from the Russian word 'volya' - воля translated as 'freedom'). All matters were discussed at the so-called ‘Cossack assembly’ where adult men gathered to decide who should be punished or fined, who should go hunting or fishing or who should be on guard duty.

Dmitry Kashirin - Ataman of Verkhneuralskaya Stanitsa of the 2nd Military Division

Southern Urals historical museumAt the head of the volnitsa was an ataman, freely elected by the adult men of the group. The ataman was highly respected and his advice heeded. At the same time, his power was not authoritarian. Furthermore, at any time, a new ataman could be elected or the incumbent himself could decide to step down.

A Cossack without a horse is like a soldier without a gun. A Cossack without a horse is considered a complete orphan. A Cossack can stay hungry, but his horse is always well fed. These sayings seem to amply reflect the role horses play in the life of a Cossack.

Stallion Osman, taken at the fall of Plevna, during the Russo-Turkish war 1878 - 1885

MAMM/MDF/russiainphoto.ruSimply put, a Cossack without a horse is not a Cossack. Cossacks learn to ride from an early age. The loss of a faithful horse is mourned like the loss of a close relative. Throughout history, Cossacks joined the regular army in cavalry (mounted) units, although there were Cossack foot regiments, too.

The shashka (saber) was as much an essential attribute of a real Cossack as his horse. It’s a long, slightly curving blade designed for stabbing and hacking. A Cossack wore his saber on his belt at all times and all but slept with it next to him. A good illustration is, for instance, Ilya Repin’s painting ‘Zaporozhian Cossacks write a letter to the Turkish Sultan’.

Ilya Repin Reply of the Zaporozhian Cossacks (Cossacks of Saporog Are Drafting a Manifesto), 1880–1891

The State Russian MuseumThe scene takes place during the Russo-Turkish war of the 17th century and, even in their relaxed mood, the Cossacks do not part with their sabers, which poke out from every part of the painting. Incidentally, in the legendary letter, the Cossacks employ the most vivid expressions to direct curses and insults at the Sultan himself and the painting shows them roaring with laughter as they think up scathing phrases (the most innocent of which is “you pig face”).

Cossacks could also perform the most improbable tricks with their sabers - in some ways, flanirovka, or sword spinning, resembles the stunt riding on horseback known as dzhigitovka, except there’s no horse involved. Without further ado, here is a video to check out.

The fashion and traditions of the Cossack look and Cossack hairstyle differed in different regions and at different times: Some Cossacks left a topknot on their otherwise shaven head, others grew a drooping mustache and others still went around with unshaven beards. But, many had the fur papakha hat in common.

Kuban Cossacks in Krasnodar

Vladimir Velengurin/TASSIt was originally the traditional male headdress among the ethnic groups of the Caucasus and Central Asia. But it subsequently “infiltrated” the Cossack troops. In Russia in the 15th century, the southern Cossacks, or Don Cossacks, were even known as Cherkasy, because of confusion with the Caucasian ethnic group, the Cherkesy (Circassians). Find out more on the papakha here.

Kuban Cossacks on Red Square during the VIctory Parade of June 24, 1945

Alexander Kiyan (CC BY-SA 3.0)The breast pockets known as gazyrs (Russian plural: “gazyry”), which were sewn onto the breast of a cherkeska caftan (another traditional item of Cossack dress), are a further feature impossible to imagine a Cossack being without.

A still from 'Kidnapping, Caucasian Style' movie

Leonid Gaidai/Mosfilm, 1967One might think they were designed for holding cigars or cigarettes (as the joke went in the hit Soviet movie ‘Kidnapping, Caucasian Style!’, 1967), but the pockets were actually intended to hold and keep gunpowder dry. Read more about gazyrshere.

Alexander Dutov, Colonel of the General Staff of the Tsarist Army, ataman of the Orenburg Cossack Army, 1920-1921

Southern Urals historical museumThe extremely baggy trousers tapering towards the shins called sharovary were another item of traditional dress for many Cossacks. They were frequently adorned with stripes on each side. Cossack troops also wore straight trousers, as well as the galliffet-type riding breeches that were to become a standard feature of Red Army uniform. A pair of red revolutionary sharovary was an honorary award in the Red Army cavalry for exceptional bravery (there is a striking scene involving this award in the Soviet movie ‘Officers’, 1971).

The kazachok has a lot in common with the Ukrainian folk dance hopak and historians can’t agree on which came first. The main elements of the kazachok are: squat kicks in which first one leg and then the other are alternately thrust forward into the air; high leaps with legs extended in opposite directions. The most varied acrobatic turns and flips were demonstrated by dashing Cossack prowess. These moves also subsequently migrated to the Soviet sailor’s dance, the yablochko.

The kazachok starts slowly, even gently, but then, the tempo builds up and the dancing becomes really boisterous. Below is the orchestral fantasia ‘Kazachok’ by composer Alexander Dargomyzhsky from 1864.

Dear readers,

Our website and social media accounts are under threat of being restricted or banned, due to the current circumstances. So, to keep up with our latest content, simply do the following:

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox