French artist Louis Caravaque arrived in Russia for the first time in 1716, at the invitation of Tsar Peter the Great “to execute portraits and battles”. The contract was for three years, but, in the end, Caravaque, a native of Marseilles, decided to stay for the rest of his life.

His artistic range was very broad: He depicted battle scenes from the Great Northern War against Sweden, decorated royal residences and even painted icons for Orthodox churches. His trademark genre, however, was portraiture.

The Frenchman painted numerous portraits of Russian monarchs and members of their families, which struck compatriots with their extraordinary ability to capture a likeness and their fine detailing. In addition, Louis Caravaque trained a number of Russian painters and organized the first life classes from the nude in Russia.

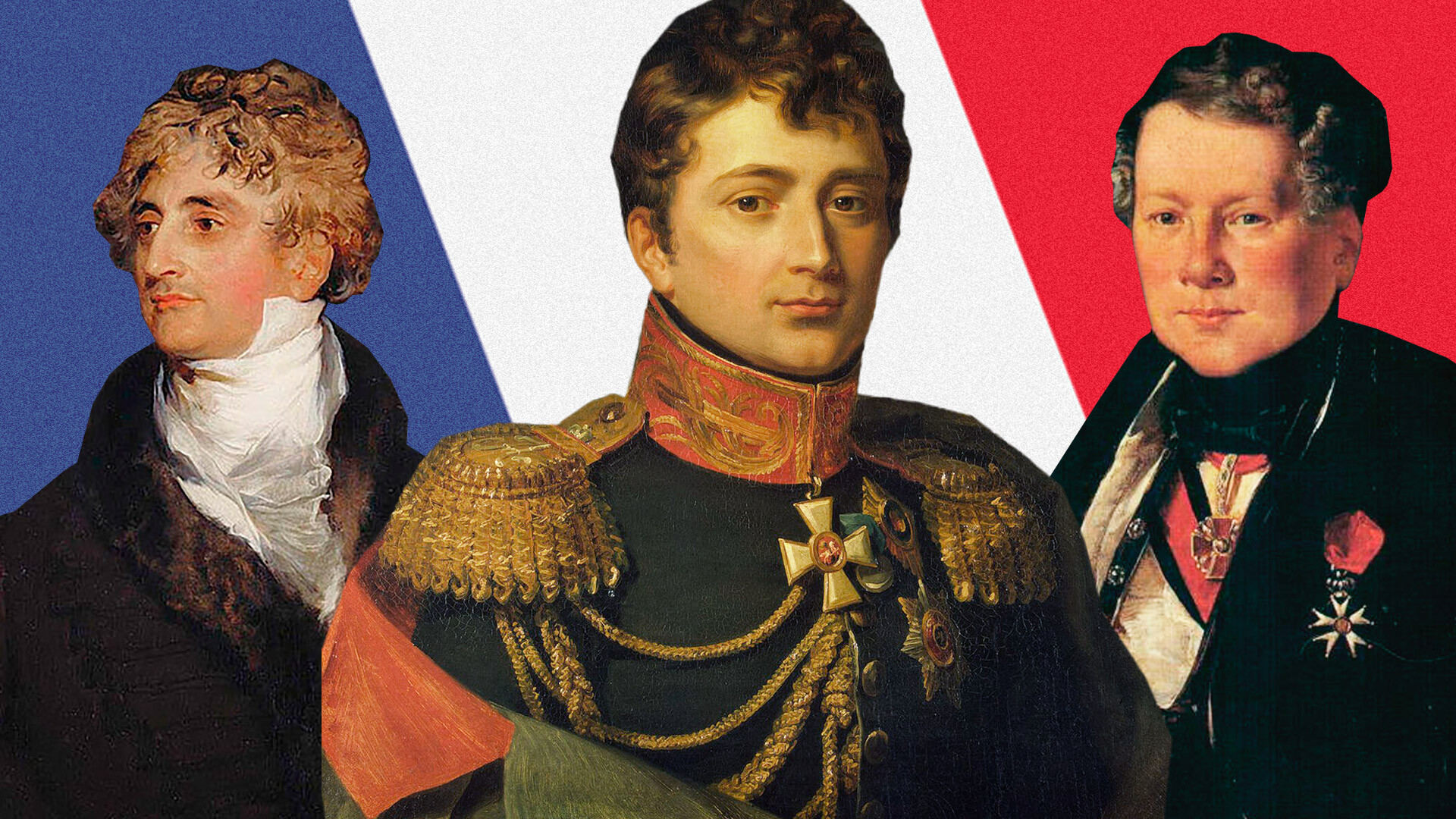

A descendant of the famous Cardinal Richelieu, Armand Emmanuel de Vignerot du Plessis, duc de Richelieu was forced to flee France after the Revolution of 1789. Once in the Russian Empire, he almost immediately went to war against the Ottoman Empire.

On December 22, 1790, the duc de Richelieu took part in the successful storming of Izmail, a Turkish fortress considered impregnable and, for his courage, was decorated with the Order of St. George Fourth Class and a gold sword. “I like people with accomplishments and, therefore, wish him all the best, although I don’t know him personally,” Empress Catherine the Great wrote about the brave Frenchman at the time.

Subsequently, the French aristocrat extensively served both the Empress and her grandson, Emperor Alexander I, both in military and civilian positions: He participated in the wars against Napoleon, was governor-general of Novorossiya (New Russia, a region north of the Black Sea), as well as governor of Odessa. He made an enormous contribution to Odessa’s prosperity and development and, later, the city readily named streets, educational institutions, alcoholic beverages and even soccer clubs after him.

The French nobleman, who had done so much for Russia, returned home in 1814. Eager to express his gratitude, Emperor Alexander I was instrumental in getting King Louis XVIII to appoint him as prime minister of the country.

The news of the Duke’s death in 1822 greatly saddened the Russian Tsar. “I mourn the duc de Richelieu as the only friend who told me the truth. He was a model of honor and veracity,” Alexander told Count de La Ferronnays, French ambassador at St. Petersburg.

As was the case with many members of the aristocracy, the French Revolution brought Guillaume Emmanuel Guignard, comte de Saint-Priest, only misery and ruin, as well as the loss of his homeland.

Guillaume Emmanuel dedicated his whole life to the struggle against his former fellow countrymen for the restoration in France of the “ancien régime” and the Bourbon dynasty. At one point, the count served in the French émigré corps of the Prince de Condé, but his military talents were only fully displayed in the army of the Russian Empire.

At Austerlitz on December 2, 1805, - a battle that ended unhappily for the Russian and Austrian troops - Guillaume Emmanuel coolly defended the village of Blasowitz at the head of the Life Guard Jaeger Battalion and was one of the last to leave the battlefield. Subsequently, the count took part in dozens of battles against Napoleon’s army on Russian and European soil and was honored with numerous awards, including the Gold Sword for Bravery with diamonds.

When, in early 1814, the Russian army entered France, Lt-Gen Guillaume Emmanuel Guignard, comte de Saint-Priest, was closer than ever before to having his dream fulfilled. But he was not fated to see the fall of Napoleonic France - in fighting at Rheims on March 13, he was fatally wounded and died shortly afterwards.

The life’s work of French architect Henri Louis Auguste Ricard de Montferrand was the construction of St. Isaac’s Cathedral - the largest Orthodox church in St. Petersburg and one of the city’s most emblematic buildings. Of the 41 years that the Frenchman lived in Russia, 40 were devoted to building this monumental edifice.

Another one of the architect’s mammoth projects was the Alexander Column in Palace Square, erected on the instructions of Tsar Nicholas I to mark the Russian victory over Napoleon. For a long time, the townspeople were afraid that the structure would fall on their heads and kept a respectful distance from it. To dispel these fears, Montferrand started taking a daily walk round the column with his dog and he stuck to this ritual until the end of his life.

In 1836, the talented Frenchman supervised work to raise the 200-ton Tsar Bell from the ground. The giant bell, which had never been used for its intended purpose, had lain in a pit in the Moscow Kremlin grounds for a whole century. The bell, which was lifted at the second attempt, was installed on a pedestal next to the Ivan the Great Bell Tower, where it stands to this day.

Far from all members of the French military laid down their arms after the defeat suffered by France in 1940. The followers of General Charles de Gaulle continued the battle against the hated enemy on other battlefields, including the Eastern Front.

In the USSR, French pilots fought the Germans in Soviet planes as members of the Normandie-Niemen air force regiment. The most successful of these was Paris-born Marcel Albert.

His comrades noted that in engagements with the enemy Albert was fearless and tenacious and always acted in a tactically masterful way. There was no pilot in the regiment who could spot an enemy aircraft in the air earlier than Marcel.

Marcel Albert, who was awarded the title of Hero of the Soviet Union, had 23 aerial victories to his name, 15 of which were shared. He conceded the title of best French pilot of World War II only to Pierre Clostermann, who fought with the Royal Air Force. The latter shot down 33 enemy planes (in 19 solo victories and 14 group kills).

Dear readers,

Our website and social media accounts are under threat of being restricted or banned, due to the current circumstances. So, to keep up with our latest content, simply do the following:

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox