“I always highly valued General Alekseev and considered him, although I had not met him often before the war, the most outstanding of our generals, the most educated, the most intelligent, the most prepared for broad military tasks,” claimed Admiral Alexander Kolchak, commander of the Black Sea Fleet during World War I.

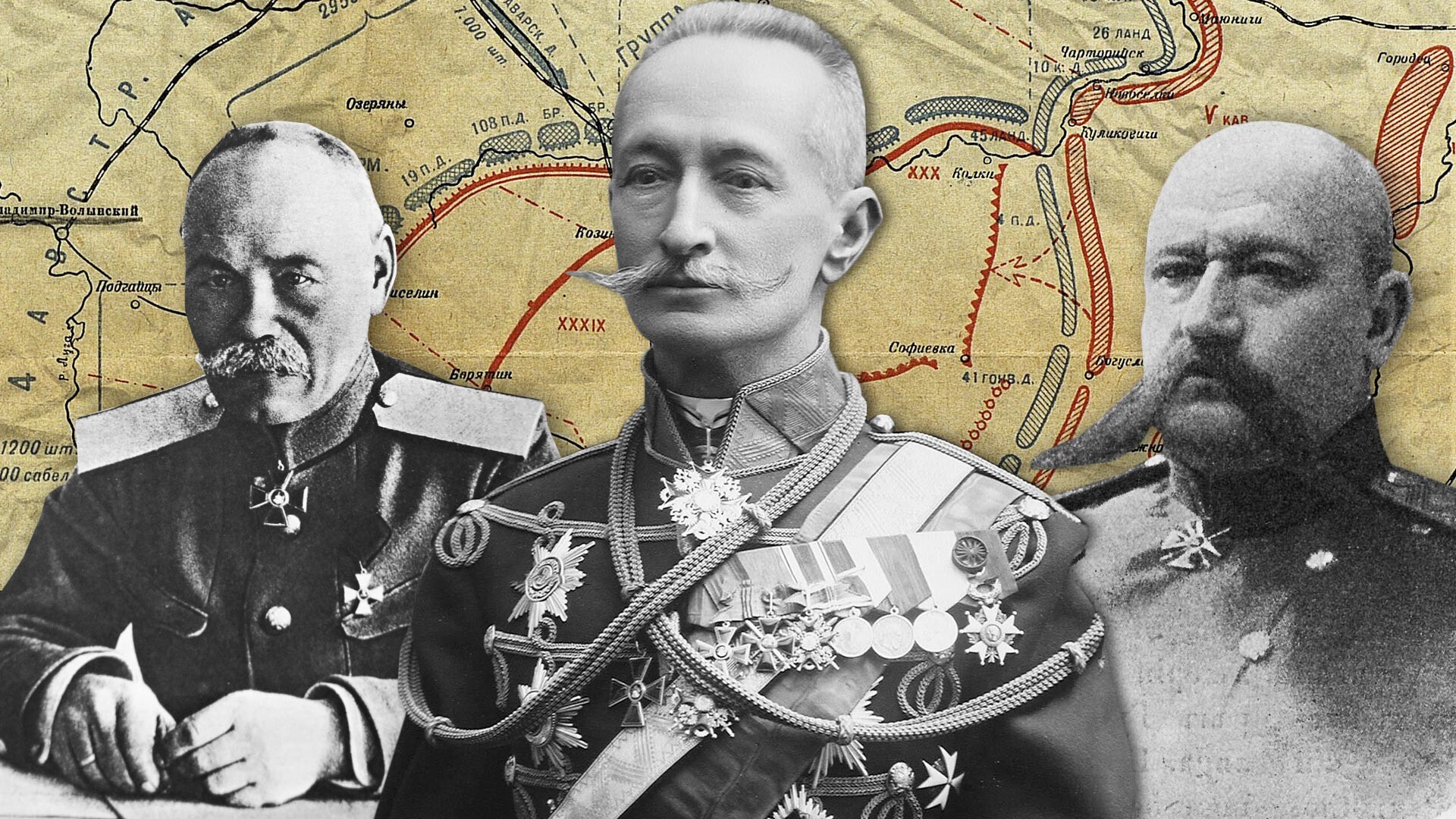

At the beginning of the world conflict, Mikhail Vasilyevich Alekseev was Chief of Staff of the Southwestern Front. In August-September 1914, during the Battle of Galicia, the front’s troops inflicted a heavy blow on Austria-Hungary, occupying almost all of Galicia and part of Austrian Poland. The Austrians did not recover from this defeat until the very end of the war.

Despite the fact that all of the glory went to General Nikolai Ivanov, Commander-in-Chief of the Southwestern Front, Alekseev was the true cause of the victory. According to General Anton Denikin, “Ivanov did not have much strategic knowledge <…> But General Alekseev was sent to him as chief of staff - a great authority in strategy and the main participant in the preliminary development of the war plan on the Austrian front… In fact, General Alekseev was the mastermind behind the armies.”

In the summer of 1915, the Central Powers, determined to pull the Russian Empire out of the war, launched a major offensive against it. As a result, having suffered a heavy defeat, the Russian armies began the ‘Great Retreat’. Despite the acute shortage of ammunition and extreme exhaustion among soldiers and officers, General Alekseev, who commanded the Northwestern Front at the time, was able to make a planned, orderly and, most importantly, timely retreat of his troops, without allowing the enemy to cut them off or surround them.

On August 18, 1915, Alekseev was appointed by Nicholas II as Chief of Staff of the Supreme Commander-in-Chief. Mikhail Vasilyevich effectively led the recovery and replenishment of the drained forces, improving their technical equipment. He directly participated in planning one of the last successful offensive operations of the Russian army in World War I - the so-called ‘Brusilovsky breakthrough’ in Volyn, Galicia, and Bukovina in the summer of 1916, which ended in a heavy defeat for the German and Austrian forces.

After the February Revolution of 1917 and the collapse of the monarchy, Alekseev was appointed Commander-in-Chief, but soon came into conflict with the new government. The general stood firmly against the “democratization” of the army initiated by the authorities (abolition of one-man command), which was supposed to raise the morale of soldiers, but, in the end, led to a rapid collapse of the armed forces. Up to his resignation on May 21, 1917, Mikhail Vasilyevich made every effort to return order and discipline to the troops, but did not succeed.

World War I began victoriously for General Aleksey Alexeevich Brusilov, commander of the Eighth Army of the Southwestern Front. In the summer of 1914, during the Battle of Galicia, his army defeated the Austro-Hungarian forces, took 20,000 prisoners, moved 150 km deep into Galicia and occupied the city of Galich.

The commander took care of his soldiers, their food and equipment, considering it to be one of his main responsibilities. At the same time, he never hesitated to turn to brutal punitive measures, if the situation demanded it.

During the disastrous ‘Great Retreat’ of the summer of 1915, the following order from Brusilov appeared: “There should be no mercy for the cowardly ones leaving their ranks or surrendering; rifle, machine-gun and cannon fire should be directed at surrendering soldiers, even if it requires ceasing fire on the enemy; we should act in the same way on those retreating or running away, and, if necessary, a mass shooting should be carried out… The weak-willed have no place among us and they must be eliminated.”

The ‘Brusilovsky breakthrough’ was the highest moment of Aleksey Alekseyevich’s career while commanding at the Southwestern Front in the Spring of 1916. He decided to break through the multilayered defense of the Austro-Hungarian forces with powerful strikes of all the armies at his disposal in several areas at the same time. Stunned, the enemy was lost, not knowing which direction to strengthen the defense and where to throw their reserves.

The Germans and Austrians had about 1.5 million men who were killed, wounded, imprisoned or went missing (the Russian losses amounted to about half a million men). They were forced to rush their reserves from other fronts, which relieved the French at Verdun and saved the Italian army from an imminent defeat at Trentino. In addition, inspired by the success of Brusilov, Romania entered the war on the side of the Entente.

“If the Western and Northern Fronts had piled all their forces on the Germans in July, they would have certainly crushed them if they followed the example of the Southwestern Front, instead of attacking single sections of each front,” Aleksey Alekseyevich lamented in his memoirs. “The Southwestern Front was certainly the weakest and there was no reason to expect it to turn the whole war around. It is good that it unexpectedly fulfilled the task given to it… Of course, the Southwestern Front alone could not have replaced the entire Russian army of millions assembled on the Russian Western Front.”

On 22 May, 1917, Aleksey Brusilov replaced Mikhail Alekseev as Supreme Commander-in-Chief but, like his predecessor, could not perform a miracle with the disintegrating army. After failing the so-called ‘June Offensive’, he was replaced by General Lavr Kornilov.

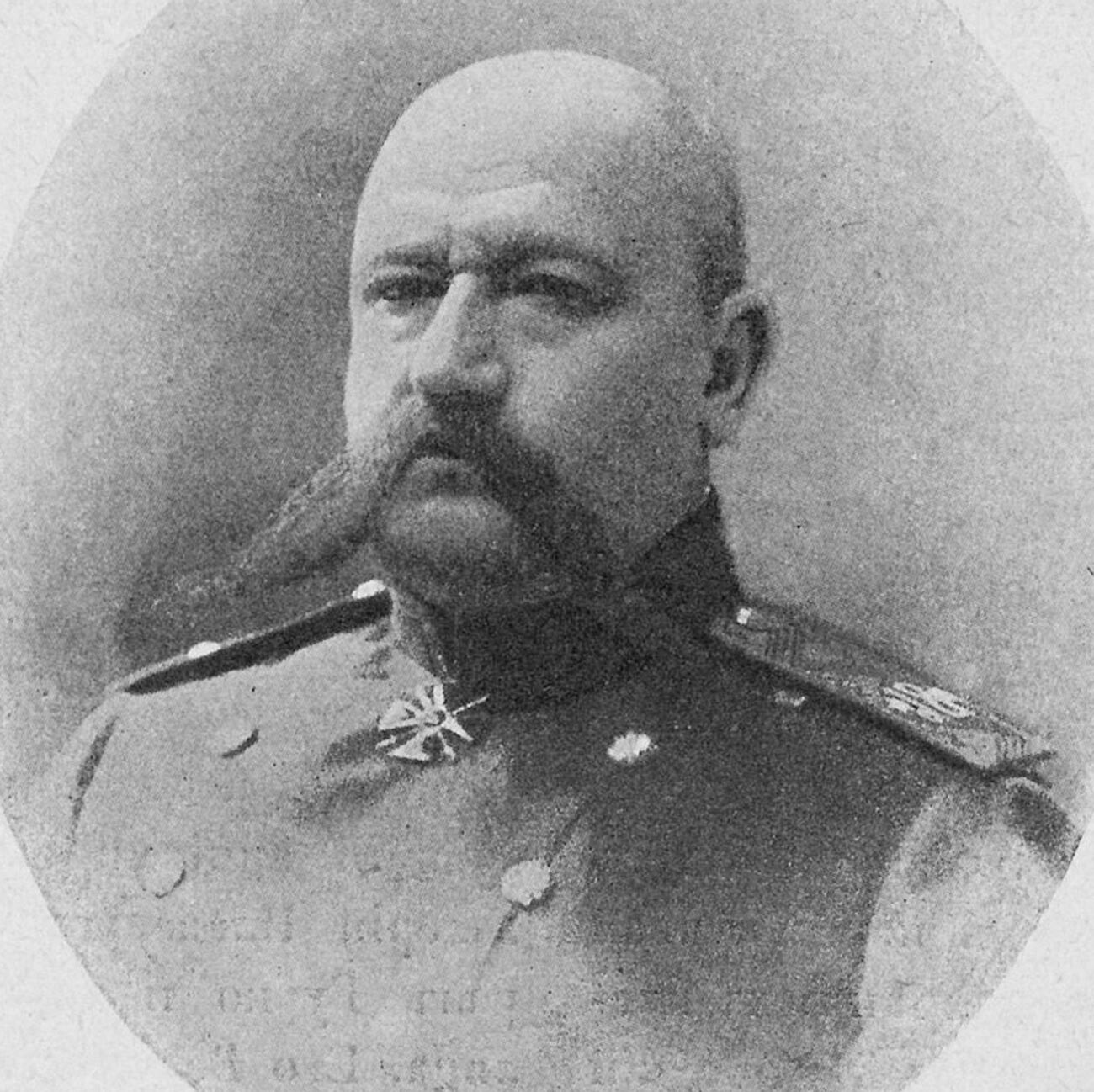

On December 29, 1914, the 3rd Ottoman army, consisting of 90,000 soldiers, besieged the town of Sarikamish in the Kars region (present-day Turkey), beyond which lay the direct route into the heart of the Russian Caucasus. Russian troops (60,000 soldiers) were not only outnumbered by the Turks, but left without leadership. Commander of the Caucasian Army General Alexander Myshlaevsky panicked and quickly fled the city, leaving his soldiers to the mercy of fate.

At this critical moment, General Nikolai Yudenich, Chief of Army Staff, who also was the temporary commander of the 2nd Turkestan Corps, took the initiative. Taking advantage of the fact that the Turks began to suffer heavy losses from frostbite, he reorganized the forces at his disposal and launched a large-scale counteroffensive that resulted in the complete defeat of the enemy. “The dying Caucasian army was saved. The iron will and indomitable energy of General Yudenich turned the wheel of fate,” enthusiastically wrote Anton Kersnovsky, a military historian of the first half of the 20th century.

Following the failure of the ‘Dardanelles Operation’ and the evacuation of Allied troops from the Gallipoli Peninsula at the end of 1915, the Turks fully concentrated on the Russian front. Under these circumstances, Yudenich, who had already become commander of the Caucasian Army by that time, decided to deliver a preventive strike.

In early January, Russian troops launched a major offensive, overturning their stunned enemy, who had believed that there would be no fighting in winter on this section of the front. The 3rd Army of the Ottoman Empire, re-formed and re-established in numbers, was once again defeated.

The Turks were retreating to the well-fortified city of Erzurum, protecting the pathway into Asia Minor. On the night of February 12, Yudenich’s soldiers dressed in white camouflage cloaks, drowning in snow and fighting their way through a heavy snowfall, started an attack. Since it was extremely difficult to see the attackers in these conditions, Turkish fire was very ineffective. The enemy retreated under the onslaught of the Russian troops, who took fort after fort. On the morning of February 16, they occupied the strategically important Erzurum almost without resistance.

“His straightforward, perfectly honest and uncommonly wholesome nature was alien to both pomp and representation, much less pose or publicity,” wrote General Boris Steifon, who served with Yudenich: “Even after Erzurum, blessed with glory and awarded the St. George Star, he could not overpower himself and go to the Stavka to introduce himself to the Emperor and thank him for his high military award; although he probably knew that if he went to the Stavka, the Adjutant General’s monogram would be waiting for him there. A convinced monarchist, he served his Emperor faithfully, without seeking rewards or encouragement.”

By the beginning of the February Revolution, the Caucasus Army remained one of the most combat-ready Russian armies. For some time, Yudenich still commanded regiments in the Caucasus, but, disagreeing with the new government on issues of tactics and strategy, was very soon dismissed as “resisting the instructions of the Provisional Government”.

Dear readers,

Our website and social media accounts are under threat of being restricted or banned, due to the current circumstances. So, to keep up with our latest content, simply do the following:

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox