Born in Oldenburg into a family of engineers, Count Burkhard Christoph von Münnich (Russianized as Khristofor Antonovich Minikh) arrived in Russia in 1721 at the invitation of Emperor Peter the Great to build roads and ports and construct bypass canals. “I have never yet had in my service a foreigner capable of implementing great plans as ably as Münnich,” observed the autocrat, who was delighted with his work.

The talented German showed his worth not just as an engineer and city chief (in 1728, he was entrusted with governing the capital of the Empire, St. Petersburg), but also as a military reformer and commander. Through his efforts, the country’s first Shlyakhetskiy (Gentry) Cadet Corps was founded and its first hussar and sapper regiments established.

Münnich successfully led troops during the War of the Polish Succession in 1734-35 and, in 1736, during a war against the Turks, the Russian army under his command invaded Crimea for the first time in its history and burned the capital of the Crimean Khanate of Bakhchysarai.

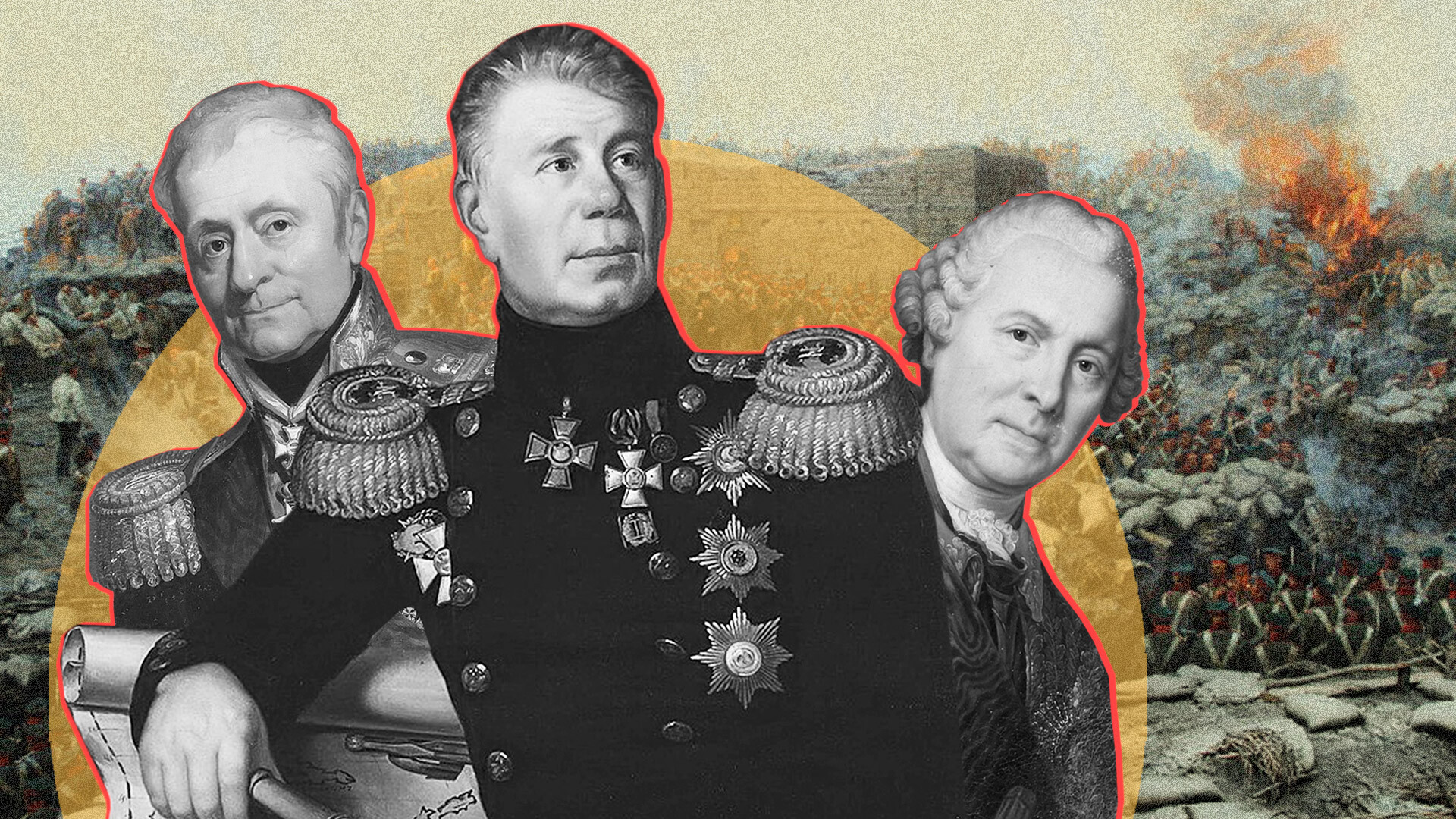

Russian victory in Crimea in 1736.

Public DomainLater, Khristofor Antonovich decided to try his hand at politics, but the endeavor almost cost him his life. In 1741, following Elizabeth Petrovna’s accession to the throne, he was falsely accused of high treason and embezzlement of state funds and sentenced to death. At the last moment, the death sentence was commuted to exile in Siberia, where the disgraced commander ended up spending all of 20 years.

Emperor Peter III recalled the 78-year-old Münnich to St. Petersburg. Münnich did not agree with many of the ruler’s political decisions, but, when a coup began against the autocrat, he remained loyal to him to the end. Catherine the Great, who ascended the throne after her husband was overthrown, didn’t punish the elderly German and appointed him governor of Siberia, which had been his dream job.

Baron Levin August Gottlieb Theophil von Bennigsen entered Russian service in 1773 when he was already an experienced military man. He had joined the army of Hanover as a 14-year-old teenager, but, having reached the rank of lieutenant-colonel, quit in order to go to what was then a distant and unknown country.

In Russia, where the Baron became known as Leonty Leontyevich, he took part in wars against the Poles, the Turks and the Persians. For bravery displayed in battle, skilful command of troops in daring surprise attacks against the enemy and successful sieges of enemy fortresses, Bennigsen was awarded several decorations and a gold sword with diamonds, as well as large estates with serfs.

On February 7,1807, near the town of Preussisch Eylau in East Prussia (now the town of Bagrationovsk in Russia’s Kaliningrad Region), the Russian army under Bennigsen’s command came up against Napoleon’s troops in a fierce battle. Over 50,000 soldiers on both sides lost their lives on the battlefield. “Piles of dead bodies were heaped with fresh piles of bodies, people fell one on top of another in their hundreds, so this whole part of the battlefield soon looked like the elevated parapet of a suddenly erected fortification,” recalled Denis Davydov, who took part in the battle.

Battle of Preussisch-Eylau.

Jean-Antoine-Siméon FortNeither side ultimately achieved a decisive victory. Nevertheless, for Napoleon, the battle was an unambiguous failure that shook the French soldiers’ faith in their invincible emperor. Napoleon only managed to take revenge on Bennigsen in the summer of that year at the Battle of Friedland.

Leonty Leontyevich went on to fight the French during the Patriotic War of 1812 and the Russian army’s foreign campaign of 1813-1814. Soon after Napoleon was defeated, Benningsen applied for retirement and returned to his native Hanover, where he spent the last years of his life.

Adam Johann von Krusenstern.

Public DomainAdmiral, navigator, explorer of the Pacific Ocean, hydrographer and one of the founders of Russian oceanology - Adam Johann von Krusenstern (known in Russia as Ivan Fyodorovich Kruzenshtern) was a truly versatile individual.

Krusenstern was born into a Baltic German noble family and, after taking part in the Russo-Swedish War of 1788-1790, was sent as a young officer to train in the Royal Navy, with which he traveled round almost the whole of the world in six years. It was then that Ivan Fyodorovch realized how limited the capabilities of the Russian navy were. In his opinion, Russians needed to mount regular round-the-world voyages, explore the world’s oceans, seek new trading partners, dispense with the services of intermediaries and enter into direct trade competition with Britain, Holland and Portugal.

Although it took some time, Krusenstern’s ideas resonated with the authorities. In 1802, he was appointed to lead the first Russian round-the-world expedition. In the course of three years, the ships Nadezhda and Neva crossed the Pacific, Atlantic and Indian oceans, visited North and South America and southern Africa and called at ports in Japan and China.

Adam Johann von Krusenstern in Avacha Bay.

Friedrich Georg WeitschDuring the voyage, Krusenstern carried out a wide range of oceanographic and meteorological studies and compiled a description of part of the Kuril Islands, the coast of Sakhalin, Kamchatka and a number of Japanese islands. He published an account of his explorations in a three-volume treatise.

Thanks to Ivan Fyodorovich, Russian ships, which until then had confined themselves to European waters, began to confidently ply the world’s oceans for the purposes of trade and science and circumnavigations of the globe became a regular occurrence. “I rejoice that you belong to Russia!” historian Nikolay Karamzin once rapturously wrote to the explorer.

“Without Totleben we would have been completely finished,” is how Admiral Pavel Nakhimov, one of the commanders of the defense of Sevastopol in the Crimean War of 1853-1856, described the work to fortify the city carried out by military engineer Franz Eduard von Totleben, a native of Mitau (modern-day Jelgava in Latvia). It was, in large part, thanks to his efforts that the principal base of the Black Sea Fleet resisted the combined forces of Britain, France, the Ottoman Empire and the Kingdom of Sardinia for almost a year.

Eduard Ivanovich (the Russified version of his name) Totleben arrived in Sevastopol not long before the approach of enemy troops and did not waste a second. Numerous redoubts and strongpoints rapidly began to be set up around the city, kilometers of sandbag walls were built and a network of trenches was established.

Siege of Sevastopol.

Franz RoubaudThere was no time to build proper fortifications of the required strength. Nevertheless, all the approaches to the city were given solid frontal and lateral defenses from both cannon and small arms. After having intended to take Sevastopol in no time, the allies were forced to switch to a systematic siege of the city.

Despite the fact that the city fell in the end, Totleben’s services were duly recognized by the authorities. He was entrusted with modernizing old networks of defensive lines and building new ones all the way from the Baltic Sea to Kiev. Eduard Ivanovich returned to the battlefield in 1877, when the experience and skills of the talented military engineer were needed in the siege of the Turkish city of Plevna (today’s Pleven in Bulgaria) by Russian troops.

Far from all Germans in Russia, however, chose the military or state service as a career. Konstantin Thon, the son of a German jeweler who had settled in St. Petersburg, devoted his life to architecture.

Thon was founder of the so-called Russian Byzantine style, in which features of Russian Classicism were combined with decorative elements drawn from Old Russian architecture. This was the style in which Konstantin Andreyevich proposed to rebuild the church of St Catherine Martyr in St. Petersburg in 1830. Emperor Nicholas I liked the design so much that he took the young architect under his wing and granted him complete creative freedom.

The Cathedral of Christ the Savior in 1896.

Public DomainIn 1839, the foundations of the Cathedral of Christ the Savior in Moscow were laid. Construction would end up taking 20 years. While the secular and religious authorities were very pleased with the cathedral, it failed to generate much enthusiasm among Muscovites. “The Church of the Savior is one of the biggest monuments to extravagant futility - it looks like a huge samovar, around which patriarchal Moscow has complacently assembled,” wrote Prince Evgenii Troubetzkoy. The cathedral was demolished in 1931 and was only rebuilt after the collapse of the Soviet Union.

The Grand Kremlin Palace.

Legion MediaKonstantin Thon was the author of many outstanding architectural projects - buildings, cathedrals and monuments, including the Moskovsky Station building in St. Petersburg and Leningradsky Station building in Moscow. Aside from the Cathedral of Christ the Savior, the architect’s most noteworthy work was the Grand Kremlin Palace, which today houses the Russian president’s ceremonial residence.

Dear readers,

Our website and social media accounts are under threat of being restricted or banned, due to the current circumstances. So, to keep up with our latest content, simply do the following:

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox