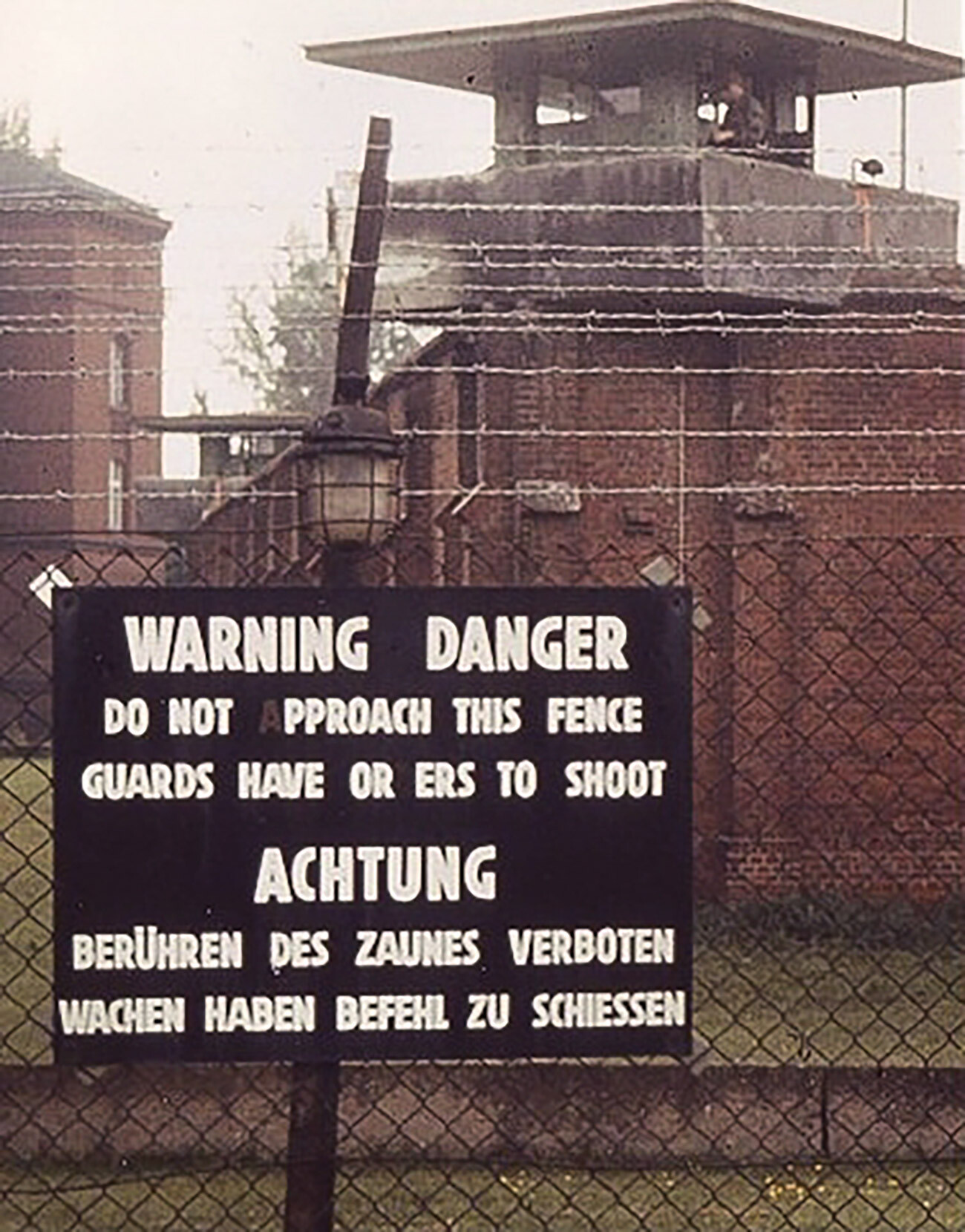

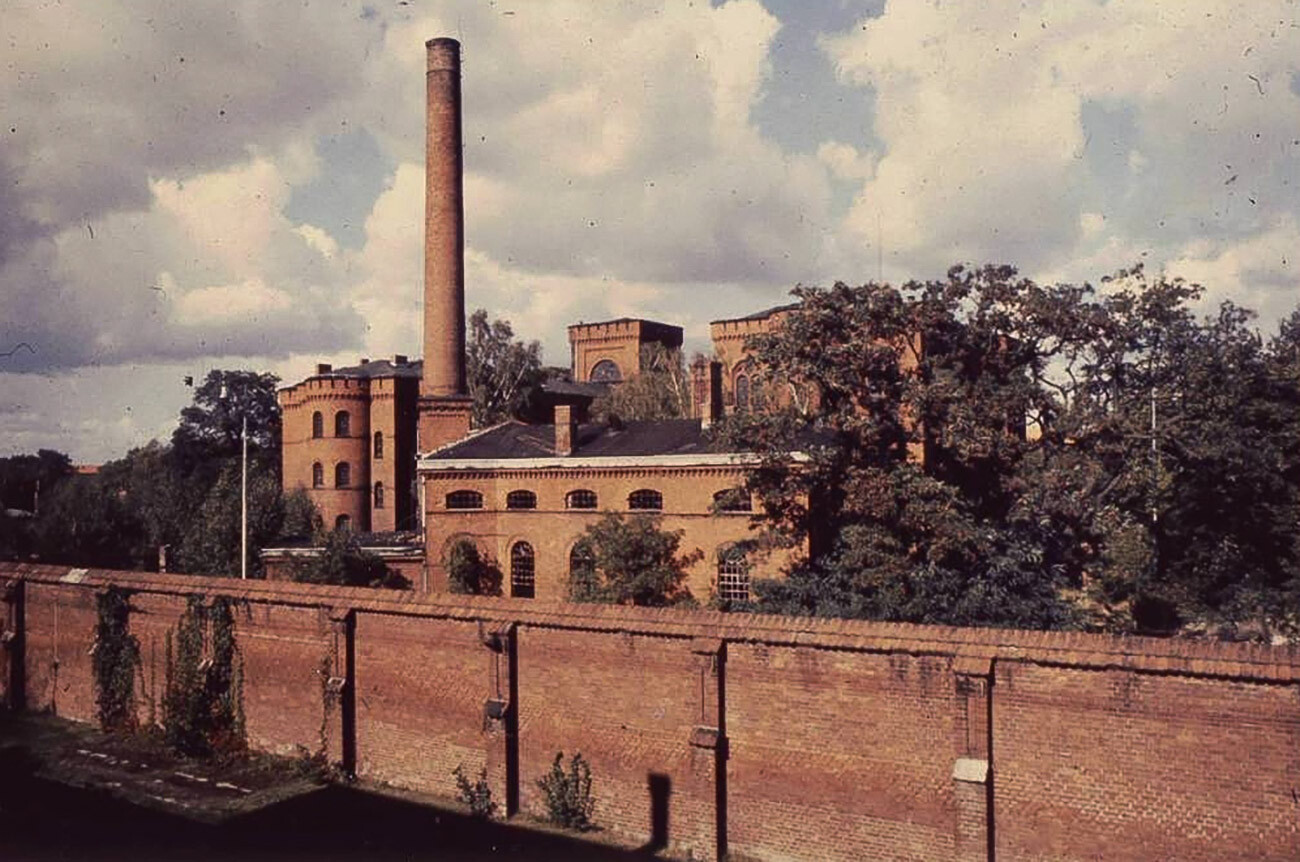

A grim four-story cross-shaped building of red brick, surrounded by a six-meter high stone wall and two barbed wire fences. That is what Spandau Prison in the western part of Berlin looked like. In the 1930s it could hold up to 800 prisoners. In the second half of the 20th century just seven prisoners served their time there.

In 1945 these men were hated by half the world. After all, they were none other than high-ranking leaders of the Third Reich convicted by the International Military Tribunal. They had on their consciences numerous war crimes and crimes against peace and humanity.

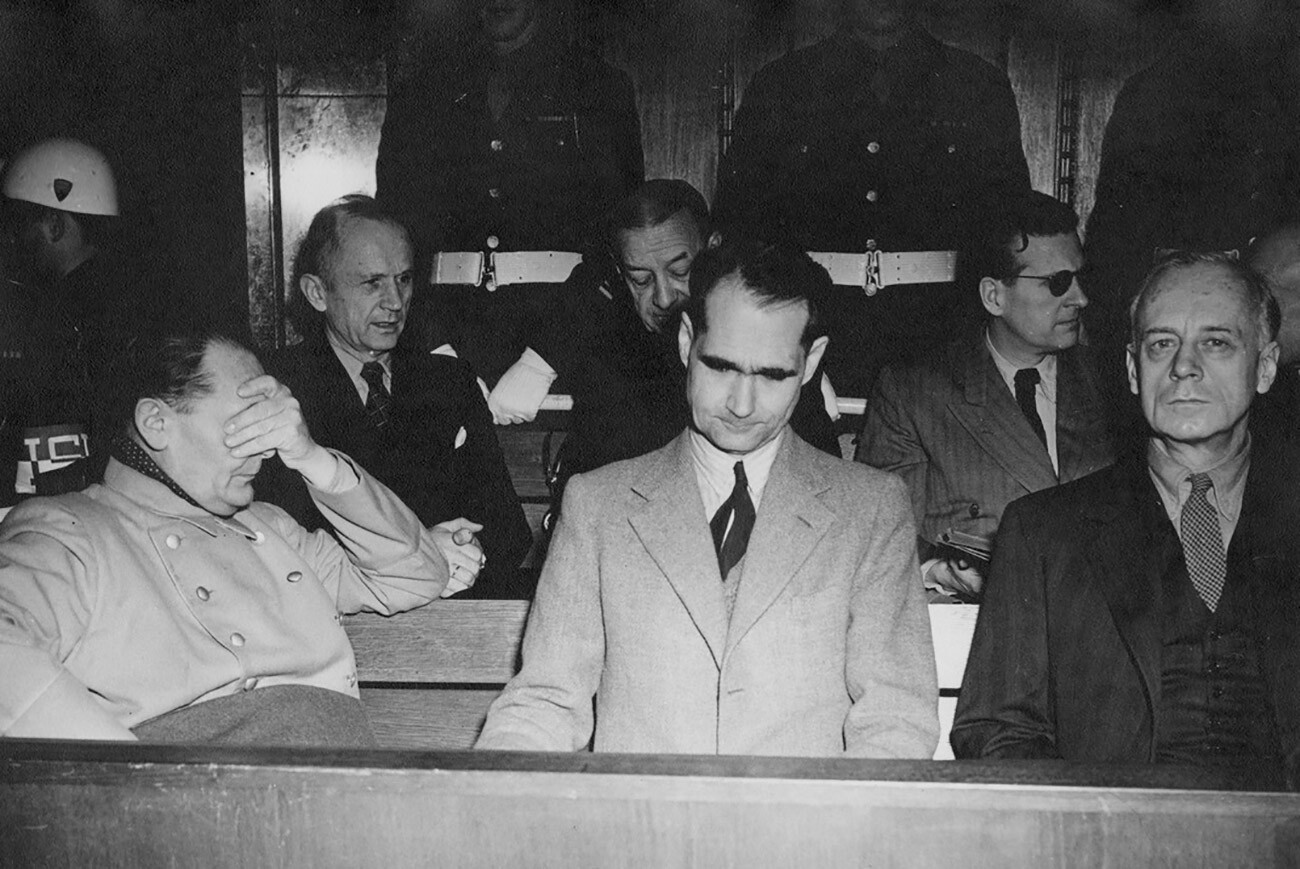

Defendants at the International Military Tribunal at Nuremberg.

Charles Alexander/Office of the United States Chief of Counsel, Harry S. Truman Library & MuseumOn June 18, 1947, all seven of the convicts who had escaped the death penalty arrived in Spandau directly from Nuremberg. They were former head of the Hitler Youth and Gauleiter (regional leader) of Vienna Baldur von Schirach; former Foreign Minister of Germany and Reich Protector of Bohemia and Moravia Konstantin von Neurath; Reich Minister of Armaments and War Production Albert Speer; Reich Minister for Economic Affairs Walther Funk; former Deputy Führer of the Nazi Party Rudolf Hess; and admirals Karl Dönitz and Erich Raeder.

Some of them were to spend 10 years, some - the rest of their lives, behind bars. All that time they were to be under the watchful eye of representatives of the four victorious powers of World War II: the USSR, the United States, Britain and France.

Berlin's Spandau Prison.

Bauamt Süd, Einofski - Herr Einofski (CC BY-SA 3.0)Spandau was given the status of inter-allied prison despite the fact that it was situated in the British Occupation Sector. The prison's administration consisted of one representative from each country. They were permanently stationed at the prison, rotating every month as presiding governors. All decisions, however, had to be taken unanimously.

Civilian personnel at the prison (except for the medical staff) were not allowed to communicate with the prisoners. In addition to French, Russian, American and British citizens, nationals of other states were also employed there. Only Germans were denied access to Spandau, although German was the administration's official language of communication

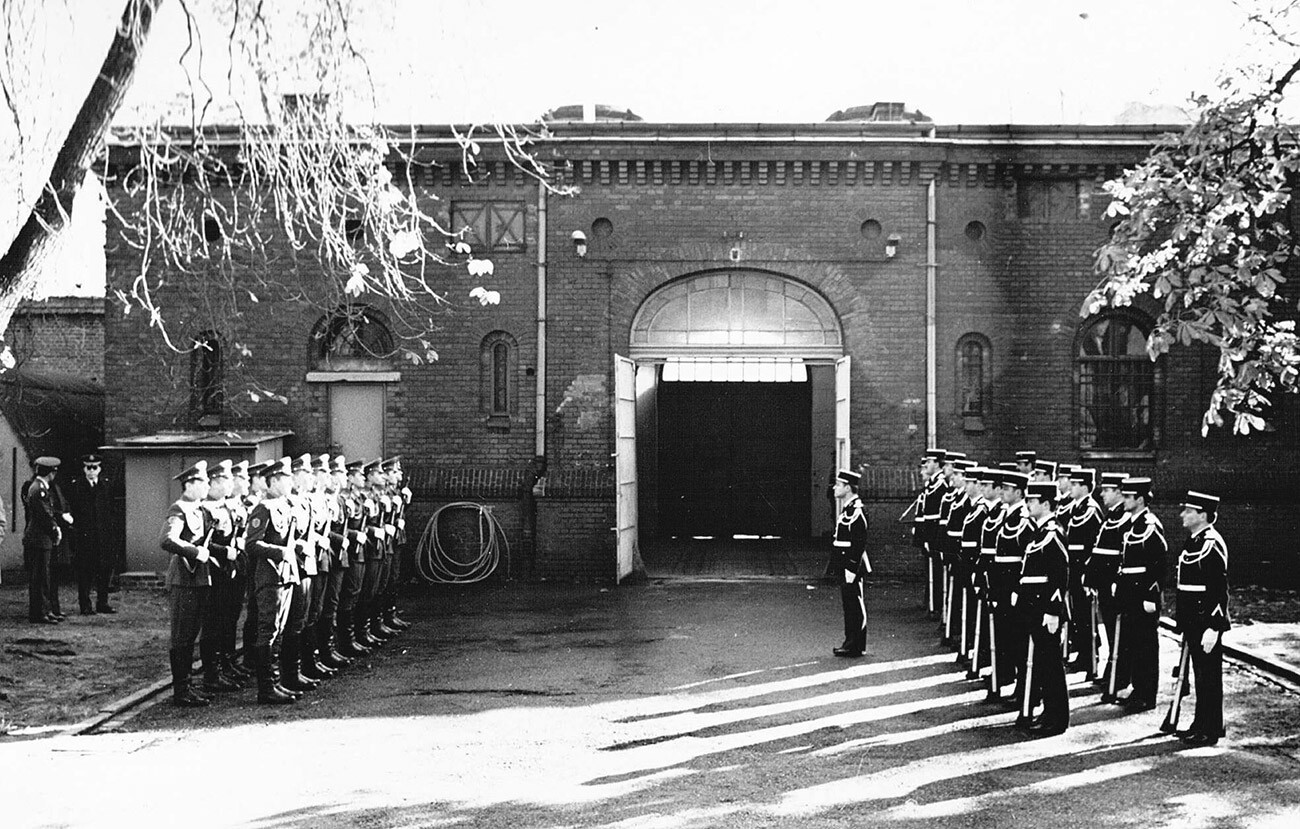

The perimeter guards of the prison changed every month. The changing of the guard from one country to another was a whole ritual, accompanied by ceremonial marching by the soldiers and reports from the guard commanders.

"We could not afford to lose face and had to show everything the soldiers of a victorious country were capable of," recalled Nikolai Sysoyev, a serviceman with the 133rd Independent Motorized Rifle Battalion. "We entered the gates of the prison at an impeccable ceremonial step, striking the steel-plated soles of our boots against the paving stones with particular zeal and creating an awful din under the vaulting of the archway."

The life of the Spandau prisoners was no picnic. They were housed in single cells and, even on walks, attending church or at work (making envelopes) they had no right of association with one another.

"Once a month we were allowed to write one brief letter, which had to go through the censorship; we could also receive one brief letter - and that had to go through the censorship too," Raeder recalled. "Quite frequently, incoming letters were not passed on to us at all or were passed on having been mutilated by the censorship - large chunks would be cut out… Once every two months, we were permitted a visit from one family member, but the meeting could last no more than 15 minutes."

Changing the guard at Spandau prison.

ALDOR46 (CC BY-SA 3.0)The Soviet administration took a much stricter line towards the Spandau prisoners than their Western counterparts. For instance, sentries who arrived for duty at the guard towers at night would make a point of noisily slamming shut the access trapdoors. The British and Americans switched on the lights in the cells several times during the night to prevent suicides, while the Soviet personnel could carry out these checks every 15 minutes.

In 1962, the USSR fiercely opposed an initiative from the Western allies to release von Schirach and Speer for "good behavior". "An alleviation of the prison regime for the main German war criminals who are serving sentences for the gravest crimes against humanity might now only embolden the militarists and revanchists who are once again nurturing aggressive plans against peace-loving nations," declared the Soviet ambassador to the GDR, Mikhail Pervukhin.

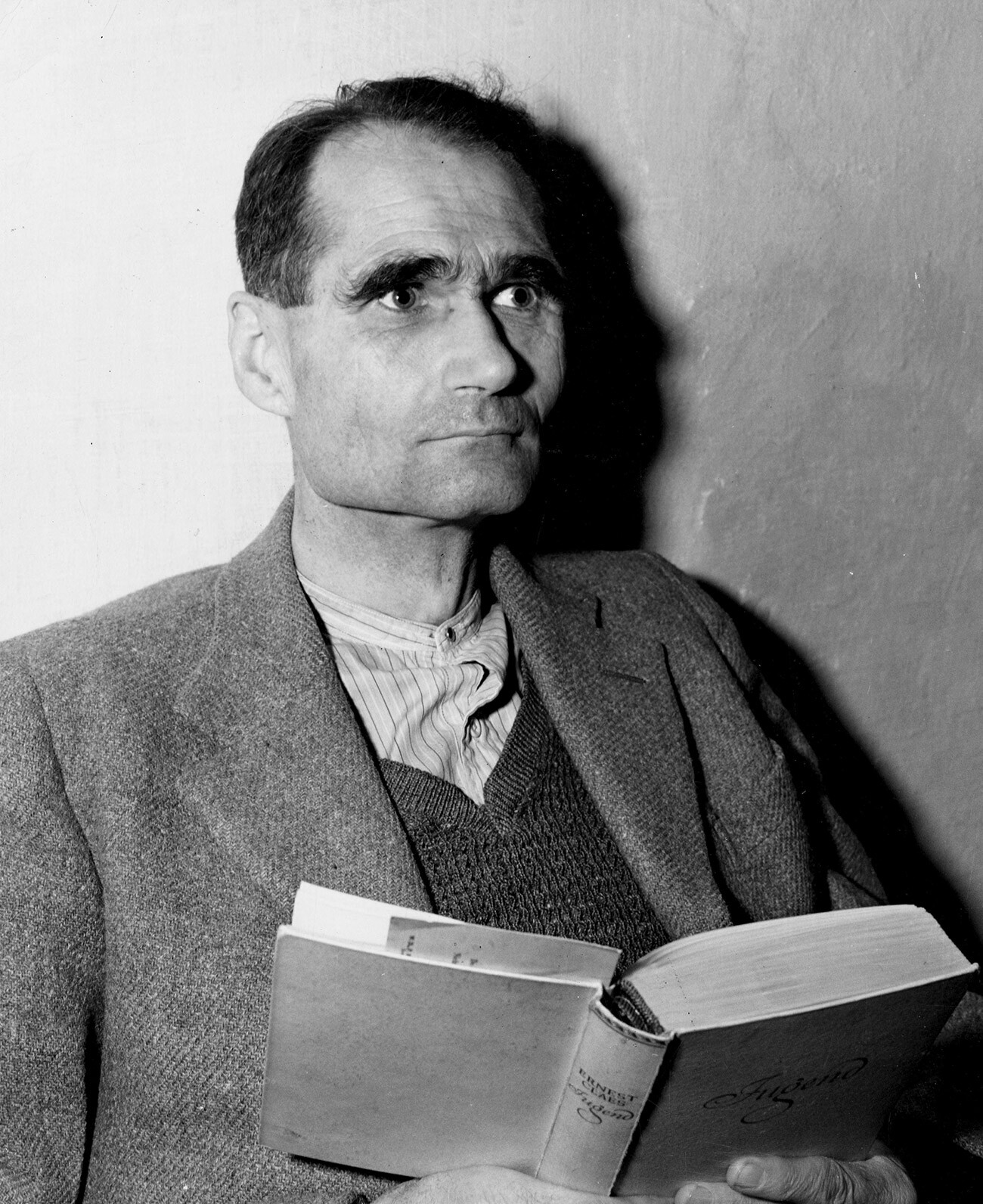

Rudolf Hess.

Legion MediaNevertheless, the prisoners of Spandau were gradually released one after another: either after having served their sentences, or for health reasons. By 1966 only one inmate remained in the prison: Rudolf Hess.

This is how a serviceman of the 133rd Battalion, Pyotr Lipeyko, recalled his first encounter with the Deputy Führer in 1985: "He was walking towards me along a narrow path in the prison garden, and one of us had to give way. At this point I was even seized by a certain fury: Why should I, an officer of the army of a victorious country, have to do so? We stopped, and I could see under a pair of shaggy eyebrows a very alert and imperious gaze that was out of keeping with his years. Hess studied the newcomer for a few moments, and then the prisoner slowly stepped off the path. Curiously, after this "duel" he started wishing me good day, even though the old Nazi never used to greet Russians."

Under agreements between the allies, after the death of the last prisoner in 1987 (Hess did manage to commit suicide) Spandau Prison was completely demolished. A large shopping center with a car park was put up where it once stood.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox