The police came to search the dormitory of workers at the Renault automobile plant in Paris on January 8, 1926. They were looking for a suspicious Chinese worker who had engaged in Communist propaganda among his colleagues. The French authorities were ready to expel this rebel named Deng Xiaoping from the country, but, by the time of the search, the Chinese Communist was already on his way to the USSR.

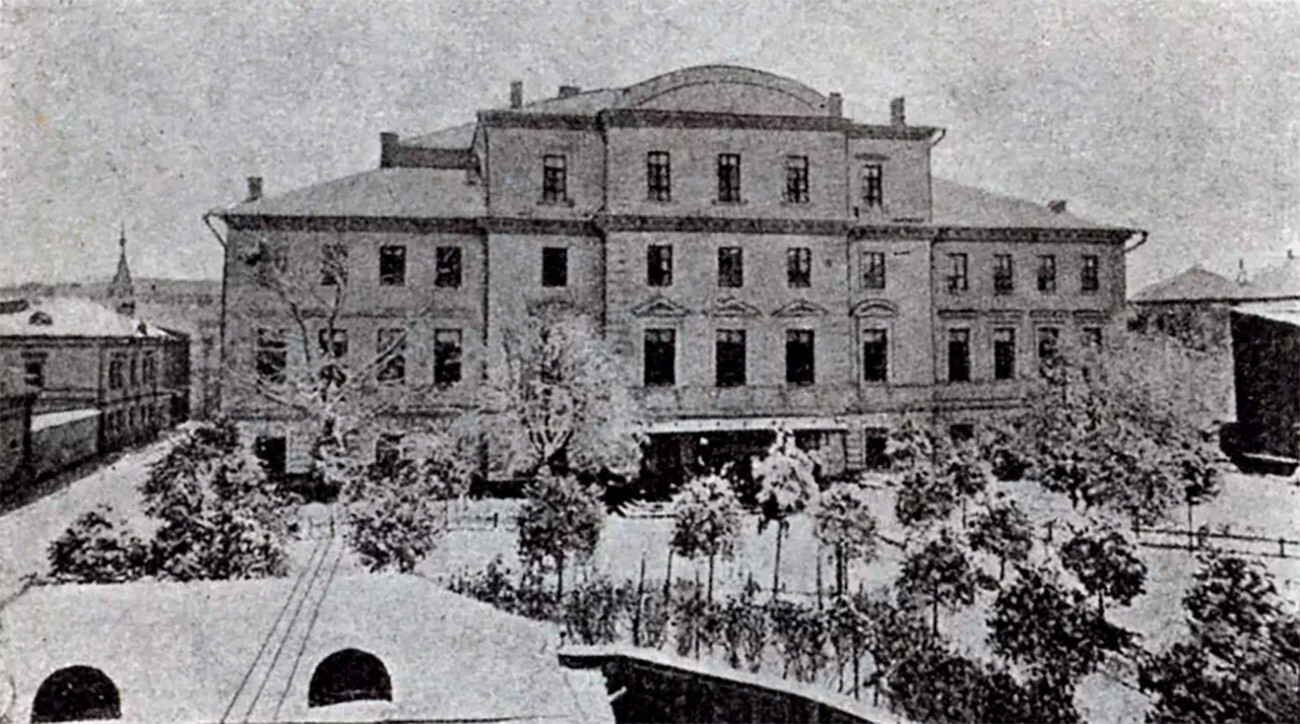

Strastnoy monastery on Pushkinskaya square, as Deng Xiaoping saw it in 1926, when he first enrolled to Communist University of the Toilers of the East, where he studied for 7 days prior to the Moscow Sun Yat-sen University.

Public domainDeng Xiaoping (and 17 other Chinese Communists) had been sent to Moscow by the European Bureau of the Communist Party of China to study the Bolshevik experience of building Communism. Arriving on January 17, comrade Deng first settled… in the Strastnoy Convent, an ancient monastery that stood on the site of the present-day Pushkin Monument in the center of Moscow, on Pushkinskaya square. There, the Communist University of the Workers of the East was located, where Deng Xiaoping was initially assigned to study.

The Chinese students in Moscow

Public domainA week after his arrival, Deng Xiaoping enrolled at the Workers’ University of China, or the Moscow Sun Yat-sen University (abbreviated Universitet Trudyaschikhsya Kitaya (UTK) in Russian), located at 16, Volkhonka Street. It used to be home to the 1st Moscow Province Gymnasium, one of the oldest in the capital. The building was in the shadow of another massive Moscow holy place – the original Cathedral of Christ the Savior, before it was demolished in 1931. The rector of the UTK was Karl Radek himself (born Karol Sobelsohn, 1885 – 1939), an associate of Lenin and Trotsky and one of the founders of the Soviet state.

Deng Xiaoping as a young man

Public domainOn January 29, 1926, comrade Deng was issued student identification card #233 under the name of ‘Ivan Sergeevich Dozorov’. He was also given a student’s kit: a suit, a coat, a pair of boots, a shirt, a towel, a washcloth, several handkerchiefs, comb, soap, shoe polish, toothbrush, and tooth powder. One couldn’t imagine a man's suit in Moscow in the 1920s without headdresses and ties, of course – but those had to be bought by the students themselves.

Chinese Communist Sheng Zhongliang, who also studied in the 1920s at the Sun Yat-sen University in Moscow, recalled: “We all followed the common fashion. We usually wore dummy jackets, like Lenin’s, or national Ukrainian blue shirts that buttoned up on the left side, although we were also given European suits. In the winter, when it was terribly cold, we were provided with winter coats and warm hats. They also gave us boots for the snow and rain and sandals for the summer.”

The Chinese students in Moscow , the 1920s

Public domainStudents were assigned to dormitories, which were located in the center of Moscow, often in former mansions of the nobility. One had to take transport from the dormitories to the university, but the student pass was valid only until classes started at 8 a.m., and those who overslept had to walk. Returning in the evening through the dark center of Moscow was dangerous – the Civil War had only recently subsided and the city was still crawling with bandits and prostitutes, so, as Sheng Zhongliang recalled: “we tried to walk in groups to reduce the risk of robbery.”

The students’ three meals a day were “plentiful in quantity and very high in quality. For breakfast, for example, we were given eggs, bread and butter, milk, sausage, tea and, sometimes, even caviar. It seems to me that the rich hardly ever had a more plentiful breakfast than ours… When we grew tired of Russian food, they hurried to please us by inviting a Chinese chef to serve.”

The building of the 1st Moscow Gymnasium, Volkhonka, 16 (demolished in the 1930s). The Moscow Sun Yat-sen University, where Deng Xiaoping studied in 1926, was located here.

Public domainStudents at the UTK studied “the Russian language, the history of the development of social forms (historical materialism), the history of the Chinese revolutionary movement and the revolutionary movements in the West and East, the history of the Bolshevik Party, economic geography, political economics, Communist Party construction, military affairs and journalism” – the classes lasted eight hours a day, six days a week. More than 150 teachers, specialists and interpreters worked with about five hundred students to deliver lectures for Chinese students in Russian with simultaneous interpretation.

READ MORE: How Russian Orthodox Christians appeared in China

Upon entering the UTK, Deng Xiaoping wrote a short autobiography in which he explained why it was important for him to study in Moscow. “We, the youth of the East, have a very strong desire for liberation, but it is difficult for us to systematize our ideas and actions… Therefore, I came to Russia primarily to learn to observe iron discipline and to receive communist baptism in order to fully communize my ideas and actions.”

Deng Xiaoping walked this alley to his university every morning at 8 from Monday to Saturday. A gas station is currently in this place.

Public domainMeanwhile, Feng Yuxiang, the future Marshal of the Republic of China, spent three months in Moscow in 1926. He managed to negotiate with the Soviet government for some material assistance and military advisers. The Soviet leadership thought it advisable to send the best students of the UTK. Among those selected was Deng Xiaoping, who was forced to interrupt his course of study. On January 12, 1927, one year (not five days) after his arrival in Moscow, Deng was discharged from Sun Yat-sen University and left for his home country on the same day.

Deng Xiaoping

Dutch National ArchivesThe final characteristic given to him by the university stated: “Very active and energetic, one of the best organizational workers. Disciplined and diligent. Puts studying in the first place. Training is very good.” In China, Comrade Deng was facing the oncoming Revolution and the Sun Yat-sen University in Moscow became, in fact, his only “communist school”.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox