The ‘Time of Troubles’ only lasted for seven years – from 1605 to 1612. But this part of Russian history was so saturated with cataclysms that it received its name. The state at that time was practically on the brink of collapsing.

One of the reasons for it was the crisis of power. Tsar Ivan the Terrible had put a lot of effort into establishing the sole, unbridled power of the monarch. In particular, he split the territory of Russia into ‘zemshchina’ and ‘oprichnina’. The latter the tsar ruled with his personal guard – ‘oprichniki’ – who conducted mass repressions and were famous for their incredible brutality. The people, having witnessed the consequences of ‘oprichnina’, couldn’t trust those who had power anymore. This, in turn, caused a deep social division; the regime in power evoked rejection in practically every strata of society – from runaway peasants and impoverished craftsmen to the army.

Nikolay Nevrev. "Oprichniki". 1870s.

Kyrgyz National Museum of Fine Arts Gapara AitievaThe internal political struggle, which erupted after the death of Ivan the Terrible, also added fuel to the fire. The tsar hadn’t left a clear mechanism for the transition of power in the conditions of the absence of any male successors. His elder son, Fyodor, died in 1598 at the age of 40 and left no heirs. The other sons of the tsar didn’t live long enough to see the throne.

The Oath of False Dmitry I to Polish King Sigism

Radishchev Art MuseumThe economy of Russia was not in its best shape, either. Ivan the Terrible’s conquest and the Livonian War (a large military conflict between Russia, the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, Sweden and Denmark that lasted 25 years) had exhausted the material resources of the country. The Great Famine of 1600-1603 then came – it ravaged thousands of large and small households across Russia, leaving up to half a million people without sustenance. The people who were left without any means of subsistence resorted to robbery and brigandage, only fanning the overall chaos.

This instability became the reason for a whole chain of other fateful events…

The ‘Time of Troubles’ spawned a whole mob of people ready to do anything just to claim the throne of the tsar. Over the entire period of the confusion with succession, at least 18 impostors tried to become the head of the country; however, none of them could hold on to power for long. The most successful of them was the first impostor, who went down in history as ‘False Dmitry I’ (read all about him here).

S. V. Ivanov. Time of Troubles. Moscow region. Impostor's army.

Public domainHis rule began in 1605 and lasted for less than a year. False Dmitry I proclaimed himself the miraculously survived son of Ivan the Terrible; he secured the support of the Polish king (he promised him lands) and entered Moscow. The boyars (the political and military elite of the country) recognized him as a legitimate ruler. First, there were rumors circulating among the elites that the new tsar was an impostor, but, when the mother of the murdered tsarevich recognized him as her son, the position of the newly made heir was bolstered.

Then, Vasily Shuisky, a boyar from an ancient bloodline, organized a coup and the murder of False Dmitry I. A part of the boyars, merchants and the military joined him and proclaimed Shuisky tsar, as a result of the Zemsky Sobor session (this was the Russian proto-parliament with representatives of different social classes).

But, the struggle for power didn’t end there.

But, after all, the position of Shuisky was very flimsy. Not all of the elite were content with the fact that he was now their ruler: there were some who believed that False Dmitry I was still alive and was the legitimate ruler. They began preparing a revolt, aiming to overthrow the new tsar. The revolt grew into a full-scale four-months-long siege of Moscow, which ended with a new impostor appearing in the Moscow Region village of Tushino – False Dmitry II.

The Shuiskys' oath to King Sigismund III in Warsaw

Lviv Historical MuseumIn essence, after the death of the first impostor, Russia had its first civil war with two centers of power – in Moscow, led by Tsar Shuisky, and in Tushino with the new impostor, False Dmitry II, and his followers. The latter were supported by the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth who were sending them their mercenaries.

Unable to deal with the ‘tushintsy’, Shuisky took the step of signing an agreement for receiving military aid from Sweden. Polish king Sigismund III perceived this agreement as anti-Polish and used it as a pretext for invading Russia.

During this conflict, a coup was staged – the boyars overthrew Shuisky and Władysław, the son of Sigismund III, received the oath of loyalty from the Moscow government and the denizens of Moscow in advance in Vilnius (he never came to Moscow, was never crowned as tsar and never occupied the throne).

Makovsky K. E. “Minin’s Appeal”

Nizhny Novgorod State Art MuseumDuring this period, Russia had no legitimate ruler, the country was practically ravaged and war raged on its territory. It was in these conditions that an idea emerged to gather and unite a liberating army that would end the Polish intervention and put an end to the ‘Time of Troubles’.

In 1611, Ryazan military commander Prokopy Lyapunov gathered the First Volunteer Army against foreign invaders. There was, however, even a divide present among the troops, which the Poles exploited, which helped them eliminate Lyapunov and other militia commanders from the inside.

The Second Volunteer Army turned out to be more cohesive. The same year, Nizhny Novgorod denizens under the leadership of Zemsky headman Kuzma Minin gathered funds to supply a new army and sent out invitations all across the country to join them. But, Minin had no military experience and, with his status, he couldn’t command nobles. So, he invited experienced commander Prince Dmitry Pozharsky to lead the Volunteer Army.

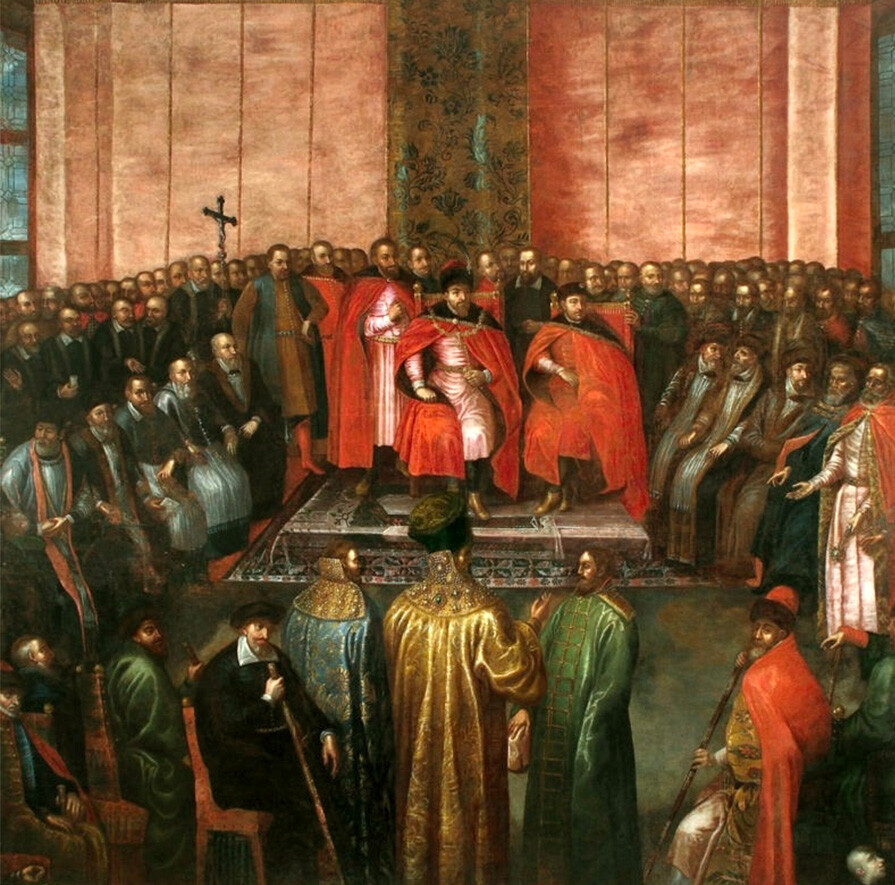

"Meeting of the Zemsky Sobor of 1613."

Public domainThis attempt turned out to be successful. In August 1612, their army routed the Poles near Moscow, in October, the Second Volunteer Army liberated the capital from occupation.

This became the turning point during the ‘Time of Troubles’. The Poles were forced to sign the capitulation pact. After liberating the capital, the Zemsky Sobor arranged the election of the new legitimate tsar. Heated arguments led to the election of the representative of another noble aristocrat line – Mikhail Fyodorovich Romanov. The latter was also related to the Rurikid dynasty, which ruled before the ‘Time of Troubles’. At the moment of his election, he was only 16 years old. In essence, he was an embodiment of a compromise that would satisfy all the clans. As such, a dynasty that would only be overthrown by the Bolsheviks in 1917 ascended to power.

The ‘Time of Troubles’ ended for Russia with colossal territorial losses: Smolensk was left under the rule of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth; a significant part of Karelia, as well as access to the Baltic Sea through the Gulf of Finland, belonged to the Swedes. Peter the Great managed to restore control over access to the sea only a century later, after which he founded St. Petersburg in 1703 on the shores of the gulf.

The country found itself in a deep economic and food crisis: The area of lands suitable for sowing shrunk 15 times, while the amount of peasants shrunk four times. For many years, in many parts of the country, population density remained significantly lower than a century before.

Tackling the consequences of the ‘Time of Troubles’ was a lengthy and painstaking process that required a lot of effort. But, the new tsar led the country out of this systemic crisis, gradually improving the financial system, international relations and simply restoring order in the regions. After his death in 1645, he left his son, Alexey Mikhailovich, with a country that hadn’t just overcome chaos, but was dynamically developing.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox