Alexander I of Russia as child (after a painting by Jean-Louis Voille)

Private collectionThe first son of Grand Duke Pavel Petrovich and Maria Feodorovna, Alexander received his name by the choice of his grandmother, Catherine the Great. He was named after the great commander Alexander the Great and was baptized after the Russian Prince Alexander Nevsky. This name was not typical for the Romanov family – before that, it was only the name of Tsarevich Alexander Petrovich (1691-1692), the son of Peter the Great, who lived for only seven months.

His grandmother took little Alexander from his mother immediately after she gave birth and he spent his childhood in Catherine's Tsarskoye Selo residence. Alexander was almost a pure-blooded German and was raised by Swiss General Frederick Lagarp. Alexander received an excellent education: he spoke French, German and English fluently, knew history, geography and mathematics. Catherine, according to the general opinion of historians, planned to transfer the throne to her beloved grandson, bypassing her son, Pavel Petrovich, whom she considered unsuitable for governing Russia.

Alexander I in 1802-1803, by Vladimir Borovikovsky

Russian MuseumThe initiator of the conspiracy against Emperor Paul I was Count Peter Palen, the St. Petersburg military governor and the emperor's closest ally. In the last months of his life, Paul was in conflict with his entire family, the situation Palen used to his advantage.

Count Palen showed Tsarevich Alexander a secret document signed by Paul, in which the emperor agreed to the imprisonment of Tsarevich Alexander, his brother Konstantin and their mother, Empress Maria Feodorovna, in the fortress.

Most historians believe that Alexander did not speak out against the conspiracy – Palen convinced the prince that his father would not be killed, but only removed from the throne. The tsarevich even asked to postpone the day of the execution of the conspiracy to March 11, 1801 – on this day, the Semenovsky Regiment, whose chief was Alexander, was on duty at the Mikhailovsky Palace.

When the plot ended with the assassination of Emperor Paul, Alexander was shocked. Jacques de Saint-Glin, who served in Russia, recalled the first day of the reign of 23-year-old Alexander: “The new emperor walked slowly, his knees seemed to buckle, his hair was loose on his head, his eyes were teary; he looked straight ahead, he sometimes hung his head, as if bowing; his whole gait, posture depicted a man, dejected by sadness and torn apart by an unexpected blow of fate. He seemed to express on his face: ‘They all took advantage of my youth, inexperience; I was deceived, I did not know that by snatching the scepter from the hands of the autocrat, I was inevitably putting his life in danger’."

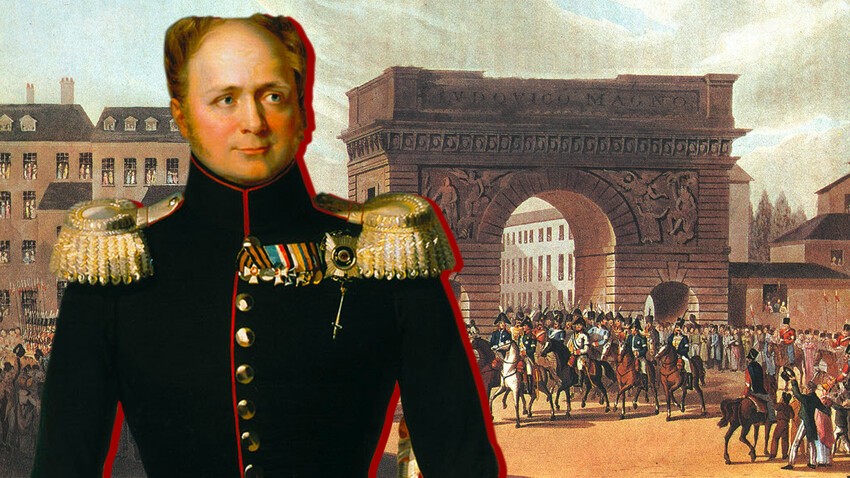

Alexander I of Russia by George Dawe

Royal CollectionAlexander's reign began promisingly – the young emperor abolished the strict military regulations that his father had introduced in St. Petersburg, returned many political prisoners from jails and exiles and behaved completely differently in public.

As historian Vladimir Tomsinov writes, Alexander "often walked the streets on foot and without an entourage, cordially responded to every bow, every greeting addressed to him. Any passerby could stop and easily talk to him. Simple, without luxury, always smiling, respectful in his treatment of anyone, young and charming, he completely changed the idea of a crowned ruler as Russian society understood it."

Emperor Alexander and empress Elizaveta Alekseevna, circa 1807

Public domainForced to live until the age of 23 between the warring courts of his father Pavel and grandmother Catherine, Alexander became proficient in hypocrisy and court intrigues. His main enemy Napoleon called Alexander a "true Byzantine" and a "northern Talma" (Francois-Joseph Talma was an outstanding French actor), hinting at the crafty and secretive disposition of the emperor.

He had the same reputation in Russia: "The Sphinx, who remained an enigma to the grave," poet Peter Vyazemsky wrote about the emperor. Having poor eyesight from birth, Alexander strictly forbade his courtiers to wear glasses. He was also deaf in his left ear (he became deaf in his youth at the Gatchina maneuvers) and, because of his reduced hearing, he constantly suspected that his aides and courtiers were making fun of him – if they laughed in the presence of the emperor, he immediately suspected that they were laughing at him. In one thing, he was exactly like his father – like Paul, Alexander was an exceptionally arrogant man.

Alexey Arakcheev by George Dawe, 1824

Hermitage MuseumFrom the very beginning of his reign, Alexander was helped to make state decisions by his friends, associates and advisers. At first, it was a "Private Committee", which included the tsar's confidants, familiar to him from his youth: Count Pavel Stroganov, Prince Viktor Kochubey, Prince Adam Czartoryski and Count Nikolai Novosiltsev. After 1803, Alexander refused their help and relied on a young jurist named Mikhail Speransky, to whom he entrusted the reforms of the civil service.

During the Patriotic War of 1812, Alexander demonstrated a rare skill for a monarch – he didn’t interfere while his military commanders were doing their job. He gave his generals and commanders-in-chief the opportunity to implement the plan of victory over Napoleon, developed by Mikhail Barclay de Tolly back in 1810 – a plan of war of attrition. Then, he led the victorious campaign of the Russian army in Europe, which ended with the capture of Paris.

In the last period of his reign, Alexander brought harsh reactionaries closer to him – the Minister of Education, Prince Alexander Golitsyn, and the Minister of War, Count Alexei Arakcheev.

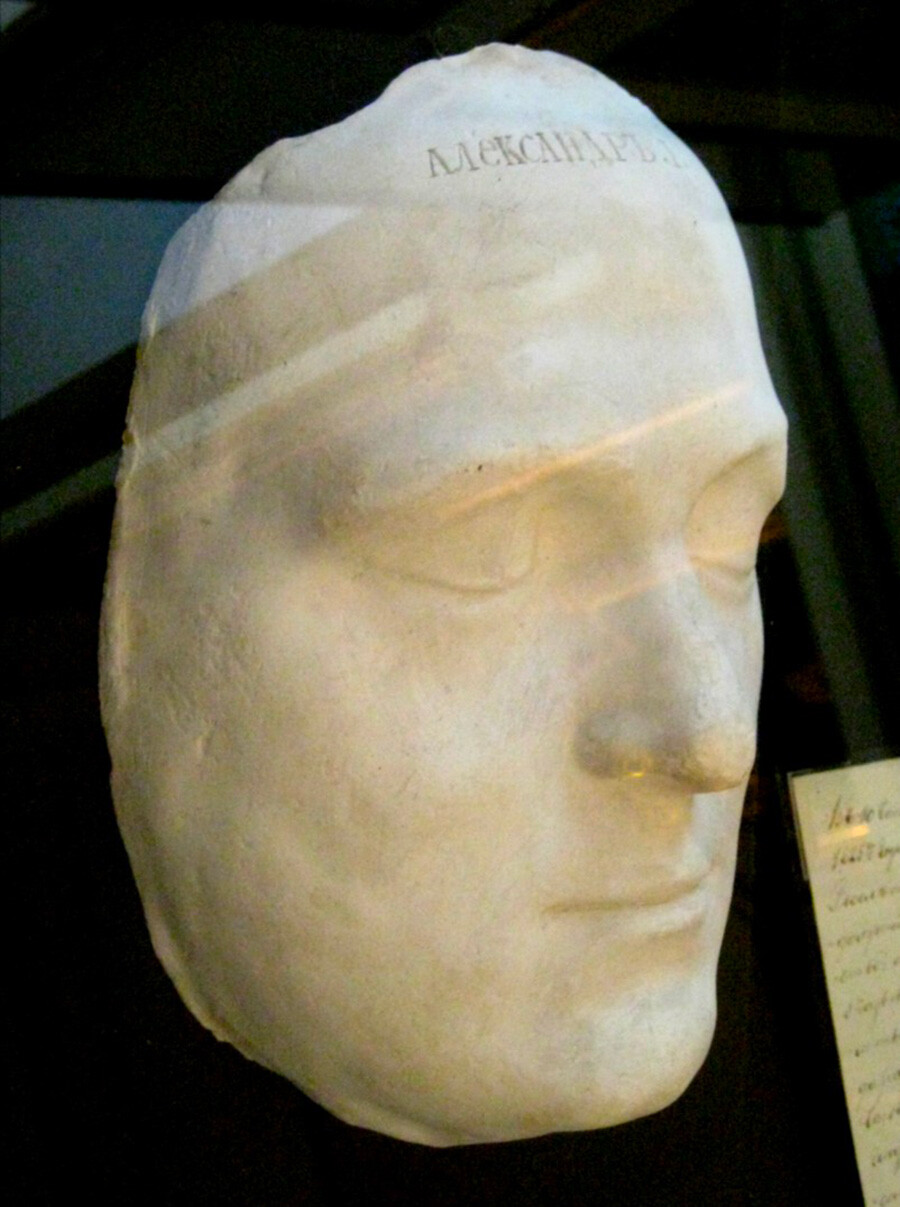

Death mask of tsar Alexander I of Russia

shakko (CC BY-SA)"In fact, I would not be displeased to throw off the burden of the crown, which weighs terribly on me," Alexander I said in 1824 to his confidant, Prince Illarion Vasilchikov. Even as a child, Tsarevich Alexander thought that ruling Russia was not his only destiny. The prince wrote to his tutor Frederick Lagarp: "When the Providence blesses me to elevate Russia to the degree of prosperity I desire for it, my first step will be to lay down the burden of government and retire to some corner of Europe, where I will serenely enjoy the goodness established in the fatherland."

Such idealism is understandable in a child, but it is strange for an adult. Nevertheless, Alexander continued to "promote" this idea, already being a tsar. In 1819, Alexander announced to his younger brother Nikolai and his wife Alexandra Feodorovna: "I have decided to resign my duties and retire from the world… I am no longer the same as I was, and I consider it my duty to leave on time." When the tsar saw that Nicholas and Maria were ready to burst into tears, he reassured them: "All this will not happen right now."

Alexander I of Russia by George Dawe

Rybinsk Museum estateIn 1823, Alexander signed a secret manifesto on the transfer of the throne to Nicholas, due to the formal abdication of the middle brother, Konstantin, from the rights to the throne. Metropolitan Filaret, Minister of Education Alexander Golitsyn and Alexei Arakcheev, loyal to the tsar, knew about the contents of the manifesto.

In 1825, Empress Elizabeth Alekseevna became seriously ill. Doctors recommended the healing air of the southern Russian town of Taganrog to her. Alexander decided to accompany his wife and left two days before her to take care of the amenities on the way and on the spot. The tsar left for Taganrog at night and, before leaving, visited the Alexander Nevsky Lavra, where he prayed for a long time to his heavenly patron.

READ MORE: How did the Decembrists revolt happen after the death of Alexander I?

When the tsar died in Taganrog on November 19 (December 1), 1825, all these rumors and details took on a terrible scale. They remembered that, leaving St. Petersburg, the tsar, in response to the question of his valet, "When do you order to expect Your Majesty?" pointed to the icon of the Savior standing in the office and replied: "He alone knows this." The mysterious death of the emperor gave rise to the legend that he really did leave the throne and go into hiding to live as a private person.

However, an old man named Feodor Kuzmich, who appeared 10 years later in Siberia, was not Alexander I. All the relatives and courtiers who saw the emperor's body in Taganrog confirmed that Alexander Pavlovich really did die of an unknown disease, which he contracted during a trip to Crimea.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox