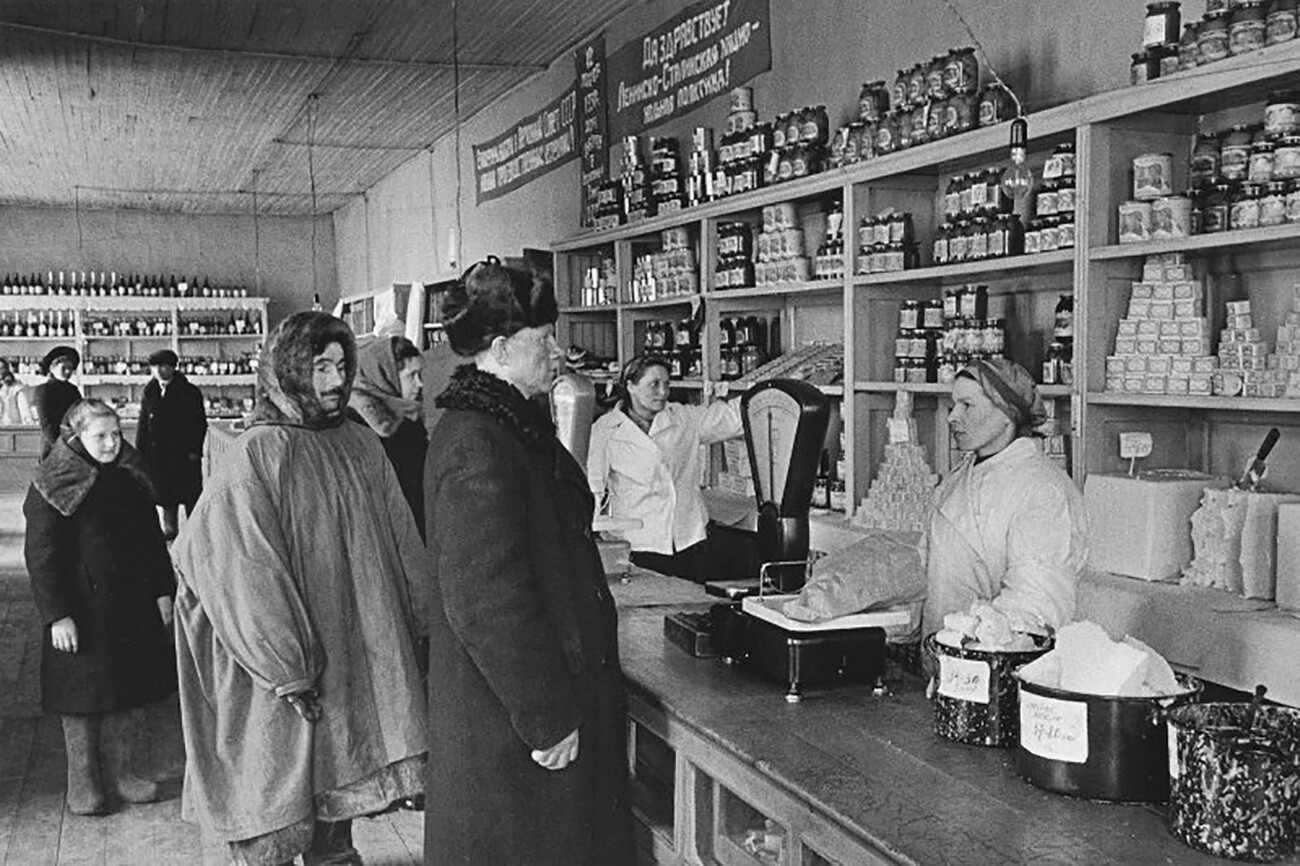

A store in Anadyr, Chukotka.

V.Chistyakov/SputnikThe economy of the Soviet Union was planned, not market-based. Prices for everything were fixed, calculated years in advance. The cost of goods was written right on the packaging. However, a number of products had not one, but three prices! Each for a certain region. Why is that?

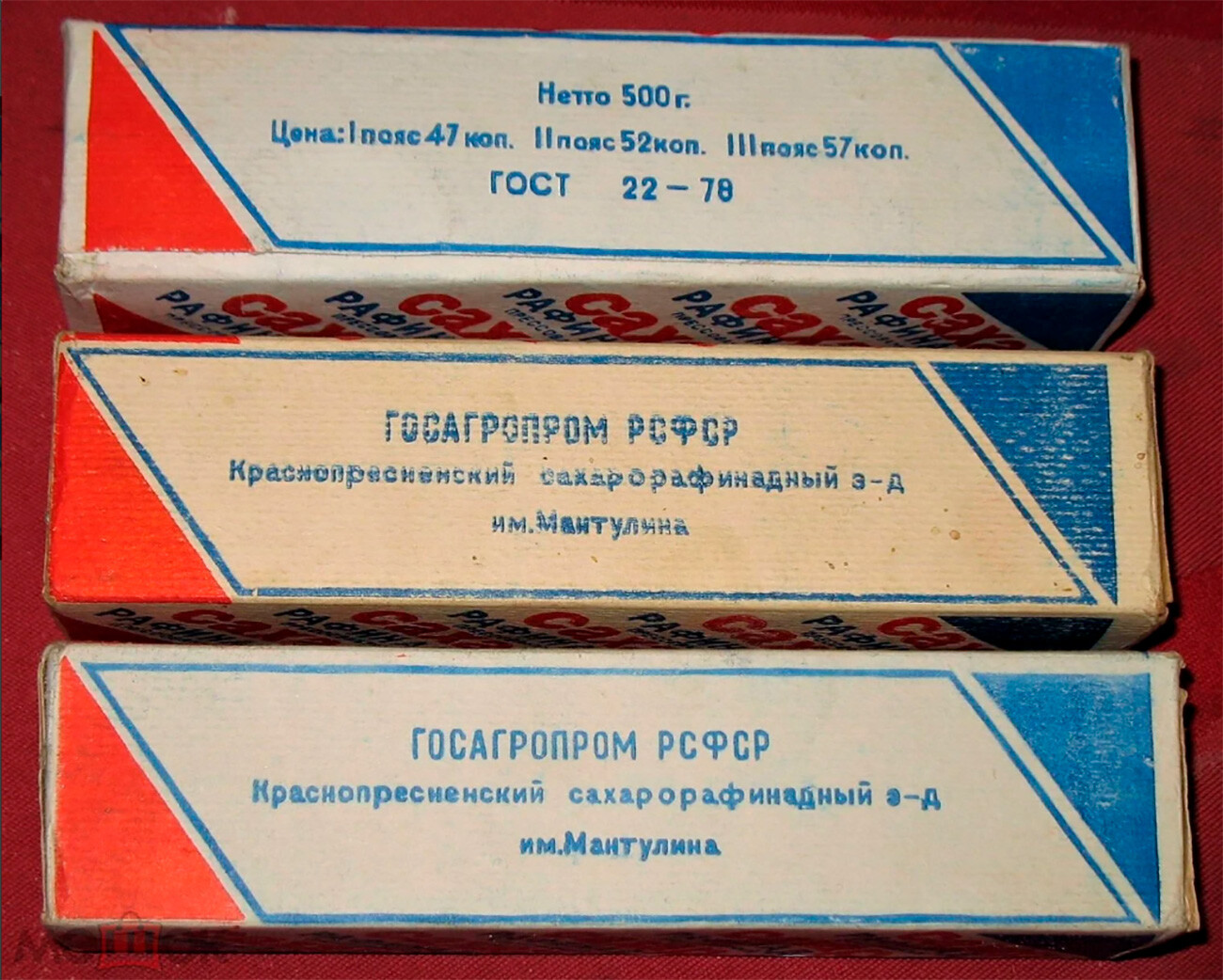

This is how the "price belts" looked like.

Pikabu.ruThe Soviet Union was the largest country in the world and, in order to distribute the costs of transporting goods, in 1935, they introduced the concept of ‘tsenovye poyasa’ (‘price belts’ aka price zones). First, for confectionery and then for other goods. The closer the place of sale was to the place of production, the lower the price.

Store of a state farm in the Kazakh SSR.

Valentin Khukhlaev/russiainphoto.ruThe first zone included union republics (Uzbek SSR, Kyrgyz SSR, Lithuanian SSR, Estonian SSR, Latvian SSR and others), as well as closed cities. It was there that the prices were minimum.

The second zone was the most part of the country, including Moscow, Moscow Region and Leningrad (now St. Petersburg).

Moscow store #31.

Semyon Mishin-Morgenstern/MAMM/MDF/russiainphoto.ruThe third zone included all the regions of the Far North, where it was difficult and expensive to deliver goods. At the same time, residents of these areas had so-called “northern bonuses” to their salaries.

Store in the town of Naryan-Mar above the Arctic Circle.

Georgy Lipskerov/MAMM/MDF/russiainphoto.ruPrices, as a rule, differed by a few kopecks, but, on a national scale, it allowed the state to save substantial sums.

For example, a pack of sugar in the first zone cost 47 kopecks, in the second – 52 kopecks, in the third – 57 kopecks.

A pack of sugar.

meshok.netAnother popular product was condensed milk. Residents of zones I and II could buy it for 55 kopecks and, in zone III, for 62 kopecks.

Sunflower oil, meanwhile, cost 1 ruble 5 kopecks, 1 ruble 10 kopecks and 1 ruble 15 kopecks, respectively.

And canned compote – 59, 65 and 73 kopecks.

Zone (‘belt’) prices were not for all things and products. As a rule, they were set for sugar, salt, canned goods and large-sized goods that required large transportation costs. For example, furniture.

But, household appliances like a meat grinder, vacuum cleaner or hair dryer cost the same everywhere.

Soviet hairdryer.

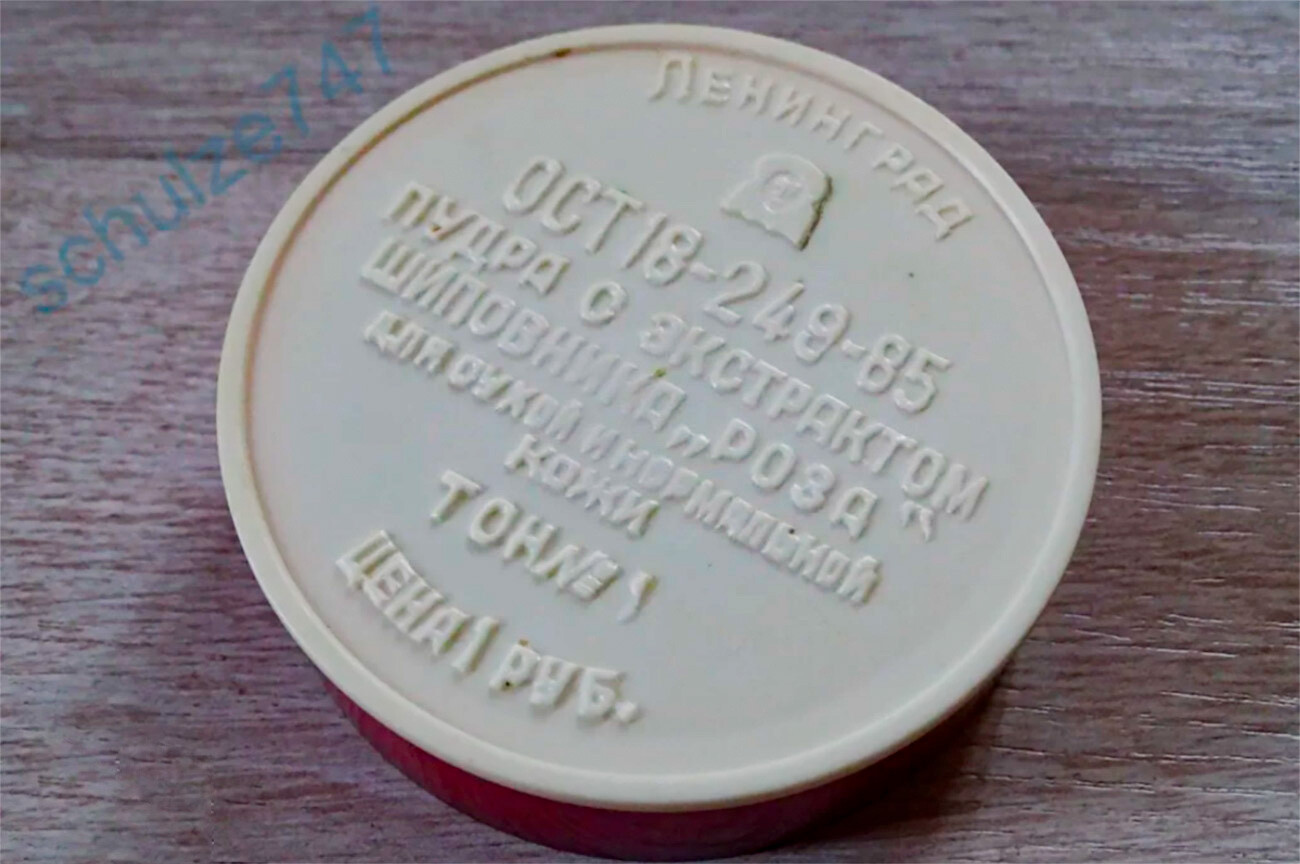

meshok.netCosmetics, clothes and shoes, as well as tea and coffee also had an all-union price.

Soviet powder costed 1 ruble.

meshok.netBut, dairy products, eggs and bread had either one or only two prices, since they were not supplied to other zones. This didn't mean that other regions didn't have ice cream or cheese, just that other producers' products were shipped there.

A pack of eggs from the Soviet times.

In addition to zone prices, the USSR had four so-called “supply categories”: special, first, second and third. The special and first categories included Moscow, Leningrad, capitals of the Union republics and “closed” (secret) cities. The second included the main territory of the country, while the third included the regions of the Far North (Yakutia, Chukotka, Murmansk region and others).

Rural store in the Tajik SSR.

Sigismund Kropivnitsky/MAMM/MDF/russiainphoto.ruIt turned out that although Moscow and Leningrad were more expensive than Riga and Tashkent, there were more goods there, including those in short supply. So, residents of other cities often went there to shop.

Store in Moscow.

Evgeny Khaldey/ MAMM/MDF/russiainphoto.ruAfter the collapse of the Soviet Union, the cost of goods became linked to free market economy principles of supply and demand, so, even today, prices can differ, even in neighboring stores.

Dear readers,

Our website and social media accounts are under threat of being restricted or banned, due to the current circumstances. So, to keep up with our latest content, simply do the following:

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox