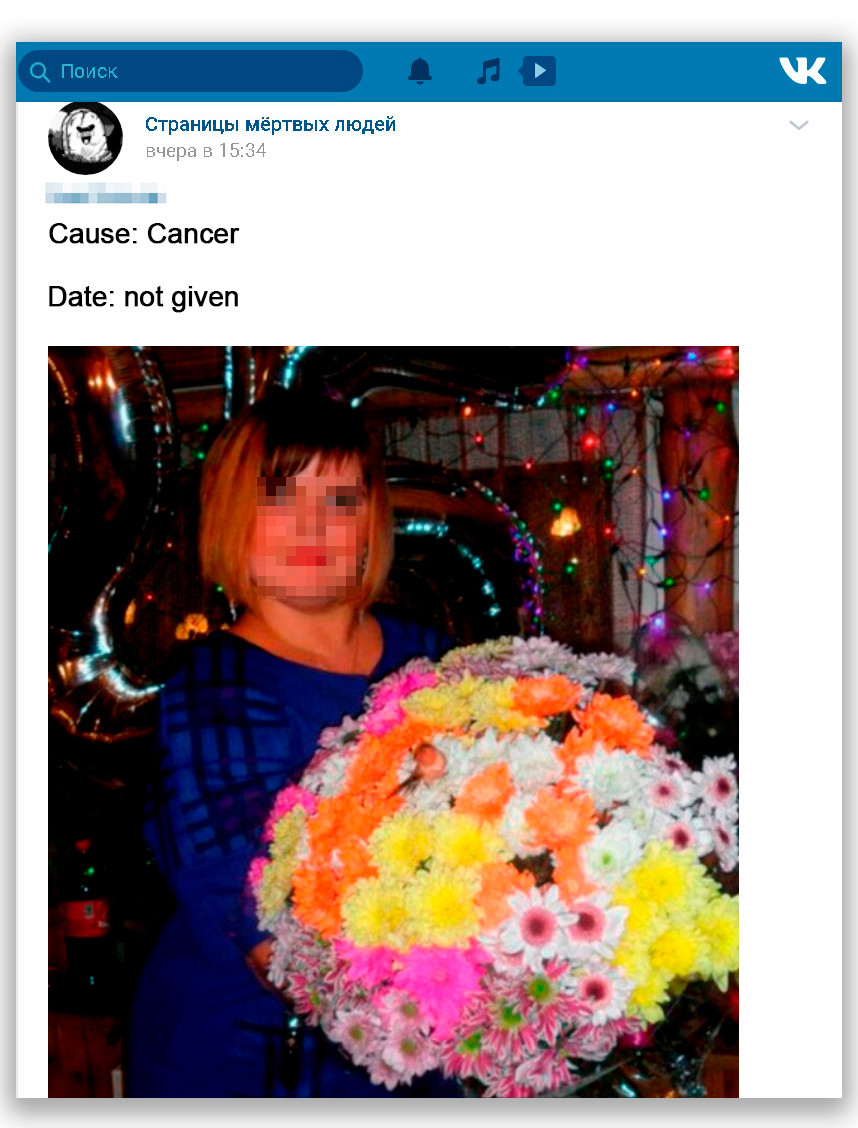

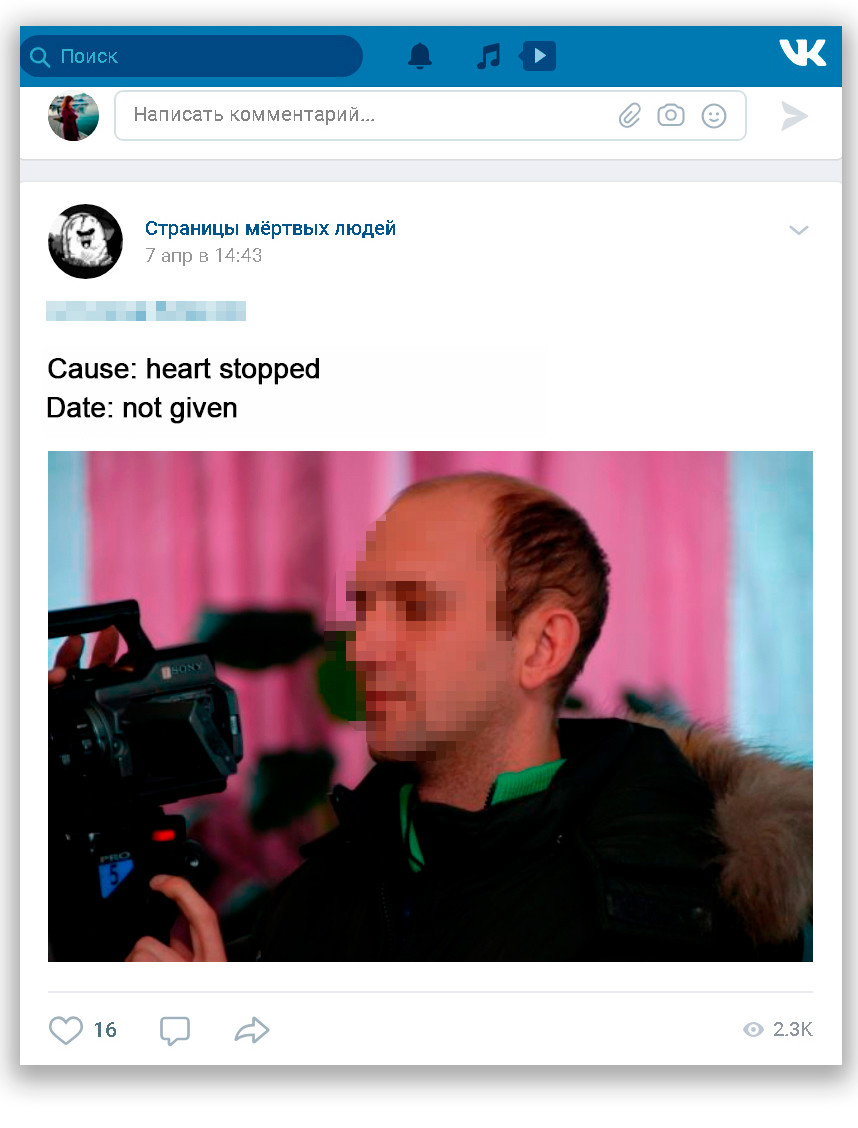

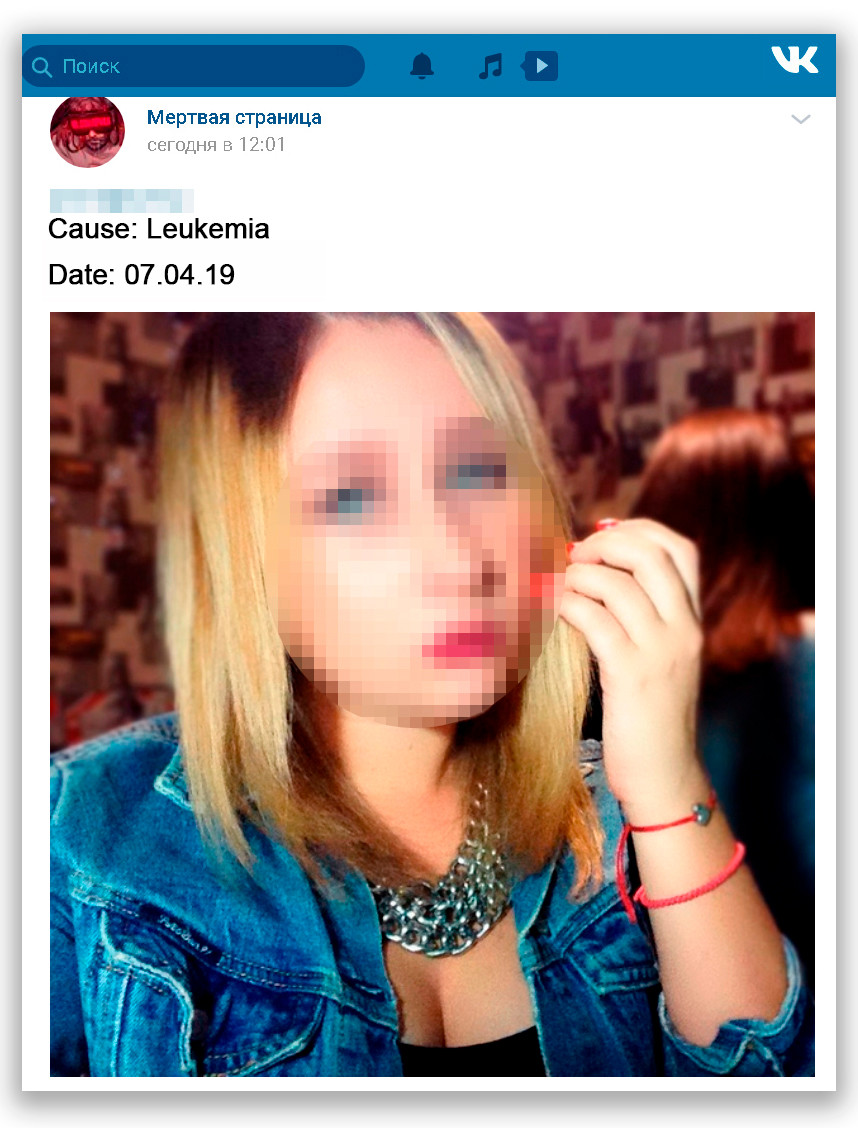

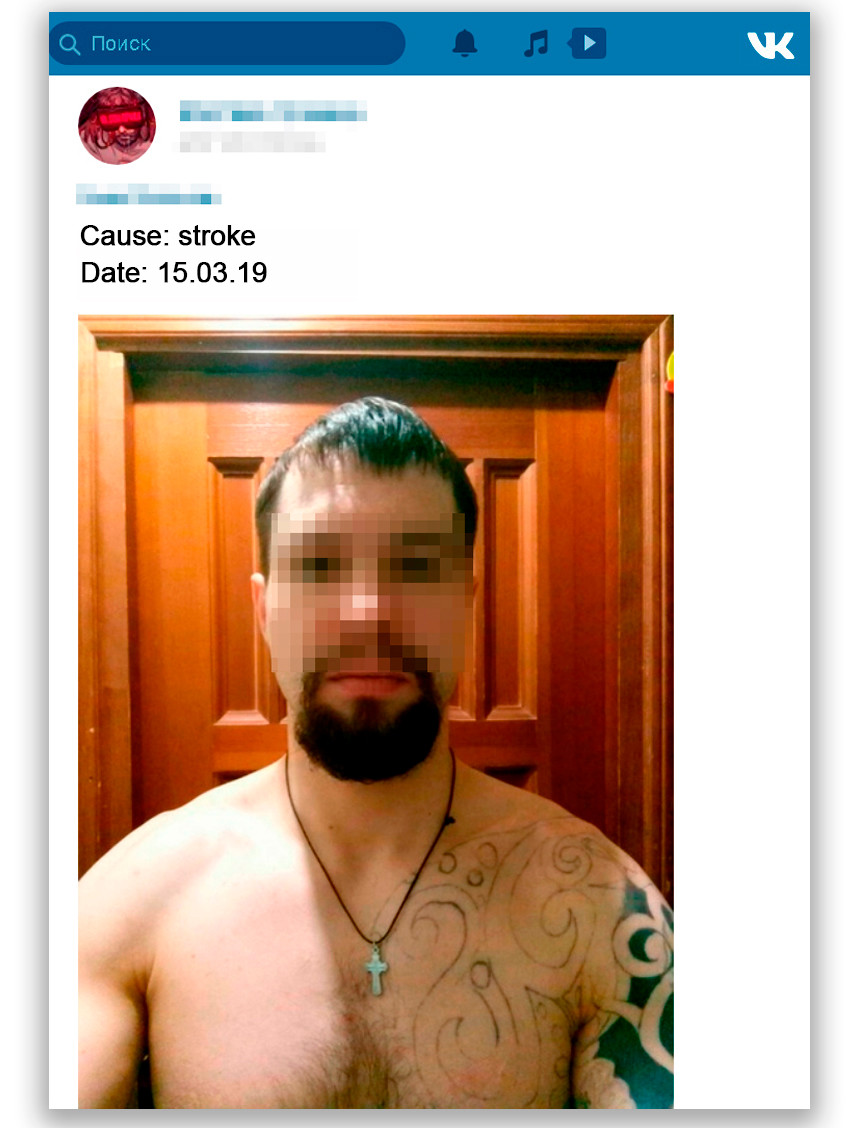

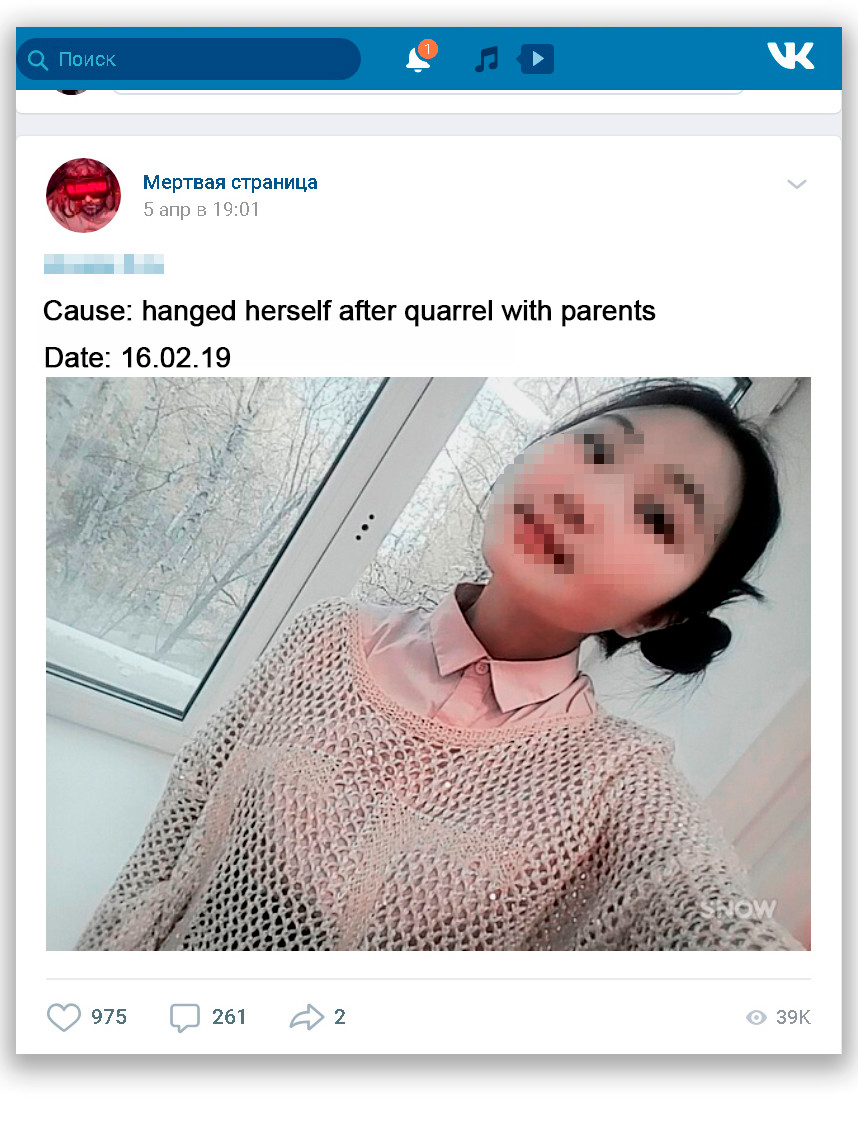

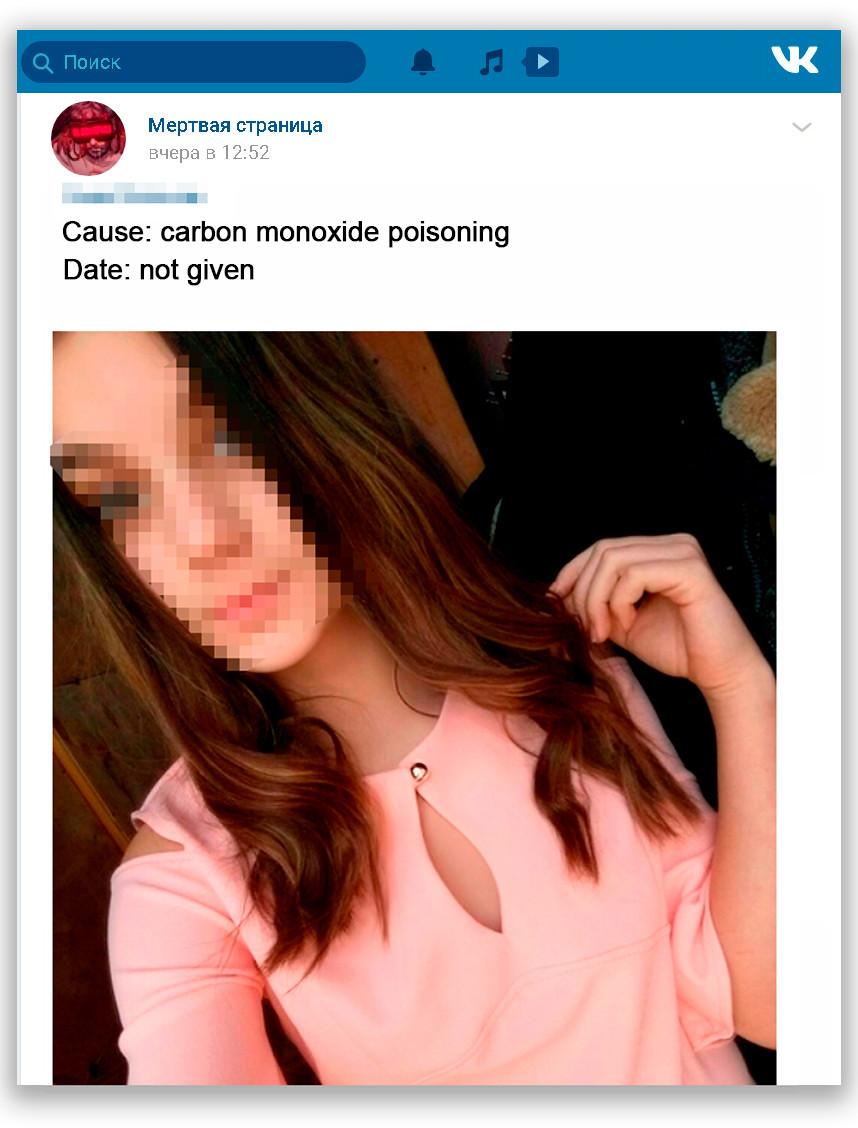

“Cancer,” “Heart stopped,” “Hanged herself”— these are some of the short, emotionless descriptions on the social media pages of deceased Russians of all ages, from a plump woman with thick eyebrows to a schoolboy with a backcombed fringe holding an iPhone.

Under each photo there is a “death certificate” in the form of a media report or messages from relatives or friends. And under each post there are at least ten likes, with comments ranging from “Sorely missed, gone far too soon” to “Good riddance.”

The grieving/insulting messages are interspersed with a bit of light-hearted native advertising. Users advertise portrait-from-photo drawing services, while online stores peddle bed linen or help with repaying a loan.

Here’s what a “virtual cemetery” looks like in the popular Russian social network Vk.com. There are dozens of communities; one of the most popular has over 300,000 members.

It is not known who originally came up with the idea to create online cemeteries. All the administrators, mostly young people under the age 25, confess that they took an interest in the “romantic” theme of death after seeing similar communities in the social network, and decided to set up their own.

20-year-old power engineer Rasul from the small Kazakh city of Kokshetau created one such virtual cemetery (172,000 subscribers and counting) three years ago when he was still in college. To begin with, he was just interested in finding out how and why people die in Russia.

It did not take long for posts to start appearing on the group page — from relatives of victims and people who had seen the RIP status on the user’s page, and the funeral ribbon in the photo. 70% of the content is created by users themselves, while the remaining 30% Rasul finds in social networks and media using keyword searches.

Given the popularity of the “cemetery,” Rasul decided to join the Vk.com advertising exchange to cash in.

“People want something new and unusual. And that’s what I give them, original content. New subscribers come from ads that I place in other communities, as well as by word of mouth,” explains Rasul.

Between a schoolgirl poisoned by carbon monoxide and a model-looking brunette murdered out of jealousy, there struts an ad for a community with photos of deranged cats. Rasul is already thinking of quitting his main job to live off the dead — the advertising money is not huge, but sufficient.

The harassment can continue even in the afterlife. “Good health to the deceased” and “Kicked the bucket at last” were a couple of messages that 33-year-old Anna from Ukhta received after news of the death of her civil-law husband Vasily appeared on one of the virtual cemeteries.

“Couldn’t care less,” “Dumbass f*cked up his life,” “Serves the sh*thead right,” etc. are among the most common comments for deceased drug addicts, alcoholics, and suicides, says one cemetery administrator. If the dead person had an unconventional appearance, that too is often ridiculed.

Anna believes this is inhuman: “I deleted a lot of the posts on my page right away. The post from the ‘cemetery’ was removed by the administration at my request. It’s very unpleasant and painful when we’re already terribly upset, but they still write these things to us,” she says.

Most administrators comply by deleting posts and blocking haters. The abundance of the latter means that requests to join the community are screened. And efforts are made not to admit anyone under the age of 18—it is children more than adults who tend to troll both the living and the dead.

One virtual cemetery with a total of 37,000 subscribers has neither ads, nor haters, only a list of deceased persons, grieving comments, and heartfelt advice about coping with the loss of a loved one.

“We don’t earn money from it. People often say they like the unique cozy atmosphere of our group,” says one of the owners proudly.

Unlike reality, in the virtual world people are not against being “buried alive.” For the chance to stage their own death and have a convincing online record of it, some are willing to pay 5,000 rubles upwards, Rasul lets it be known. He receives 2-3 such offers on a daily basis. But does not accept them.

“People want to attract public attention and be talked about — at least on the day after their virtual death. Many are simply curious to find out what people will say about them if they think they’re dead,” he believes.

Very rarely, some users ask for people they know to be virtually buried alive — either out of revenge or for fun.

“For them, it’s just a joke. They don’t realize the shock and impact on relatives and loved ones who think it’s real. Such users are permanently banned,” explains Rasul.

The craze for following not only the lives, but the deaths of strangers, like in a reality show, is the main reason why virtual cemeteries are so popular, say community owners and members.

“It’s the same sort of content as memes. It’s interesting to find out who the person was before their death, how they died, whether they deserve sympathy or contempt,” anime fan and active cemetery subscriber Dmitry is sure.

Another community member, 15-year-old schoolgirl Anastasia, on the contrary, believes that online cemeteries help people to value their own lives a little more.

“You understand that death can come just by slipping and falling over,” she says.

Above all, virtual cemeteries provide a service for victims’ friends and family, who get support and condolence, and can keep the memory of the deceased alive, reckons clinical psychologist Ruslan Molodtsov. Haters, meanwhile, take out their sadistic urges on the dead in an attempt to compensate for childhood complexes.

However, it is not just to do with complexes, but the digitalization of both modern life and “modern death,” Rasul is convinced.

“The Internet has eaten into our lives so much — news, books, movies, etc., it’s all there. We live online. So we might as well die online too,” he concludes.

The Vk.com press service states that relatives can “preserve” their loved one’s page: All information in the account is made available only to friends, and the page remains as it was the last time the deceased user logged into the social network. If desired, relatives can request the page to be deleted. To do so, they should contact the support service.

Insulting posts or comments are deleted after a complaint is made by a user.

The surnames of the interviewees have not been divulged at their request

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox