Passengers outside Aivazovsky Simferopol International Airport

Sergei Malgavko/TASSContrary to its image as a place everyone wants to leave, that is enduring in western propaganda, in the past 30 years, Russia has become home again to countless returning emigrants. Some had left the Soviet Union and came back after its demise, some left after Iron Curtain fell, in order to feel the greener grass on the other side, but chose then to return. And some are Global Russians, the sort that lived everywhere, but never quite left. What brings them all home?

Stanislav Filin with wife Ivelina and their daughter

Personal archiveStanislav Filin was born in Moscow, but spent most of his life abroad. His family remained Russian-based through most of the 1990s, but Stanislav and his mother traveled to Malta in 1994, where he attended school until 1999, only returning home for holidays. And in 1999, when he was 12, the whole family moved to Canada.

“The difference between what we expected to find, based on what we were told about this beautiful, magical place - Montreal! - and what we found when we got there, was stunning. I remember my parents in shock, asking: ‘Why are we here?’,” he recalls. And that, he adds, was even though they had just left Moscow in its “darkest hour”, crumbling from the effects of the recent banking crisis and not yet subject to the wave of refurbishment and modernisation of the upcoming Putin years.

“My parents were not impressed with Canada, they left as soon as they could, when I was old enough to be shipped off to boarding high school and college in the United States,” recalls Stanislav. He spent the seven most formative years of his life in the US, graduating from high school and earning a degree in business from Saint Joseph's University in Philadelphia. But he was even less impressed with the US than Canada. “I remember North and West Philadelphia, it was so bad, there were cars on fire, needles and prostitutes on the streets. Most Russians do not realise that there are huge areas in every U.S. city where even the police refuse to go, because it’s so dangerous. In Russia, we simply don’t have places like that!”

Having returned to Canada in 2009, Stanislav says, he was most put off by the incompetence of the healthcare service - people waiting for days to get admitted to the hospital, doctors unable to diagnose and treat common, well-known conditions. He was forced to travel to Russia to seek basic medical treatment. “In Moscow, we had to go to the ER with our daughter once, and she was in a hospital bed 30 minutes after our arrival - the delay only being down to me having to fill out forms, while hospital staff were waiting. No one in Canada would believe this,” he says.

Stanislav met Ivelina, who is from Bulgaria, in Canada in 2016, and the new couple moved back to Malta, the country he considered his second home since childhood. He had studied for an MBA at a University there. And this is where their daughter was born. “Malta is safer than North America, and has better food and nicer people. Unfortunately, it has also changed in recent years, especially since the migrant crisis. Sure, it is more technically advanced and modern now, but it is also a dirtier country, with social problems and ‘bad’ areas,” he laments.

They moved permanently to Moscow in 2019, and say they couldn’t have been happier. Stanislav works as a development director for Russia for an international telecoms company. The family say the most refreshing, liberating aspect of the move, after all, is that the income they make here affords a better lifestyle and more freedom.

“Everyone I know in the West always struggles to pay bills - all of their income is always for bills. They get promoted, they get richer, and their bills go up, because they feel pressure to move to a better area, buy a bigger house, etc.,” explains Stanislav. In Russia, he says, it is easy to have disposable income, due to the lower cost of living, free healthcare and heavily subsidized pre-schools.

Ivelina says that she feels like home in Moscow: “The people, environment and culture reminds me of Bulgaria. There are plenty of things to do. I like how clean it is. The city is built for families - playgrounds, playrooms, parks everywhere. Preschool is amazing, compared to the ones in Canada. Children sleep in beds, not on the floor. I miss nothing about Canada, except for some small material things and my friends there. I miss Malta a bit, because we started to build our family there and there are a lot of fond memories. But Moscow is where home is now.”

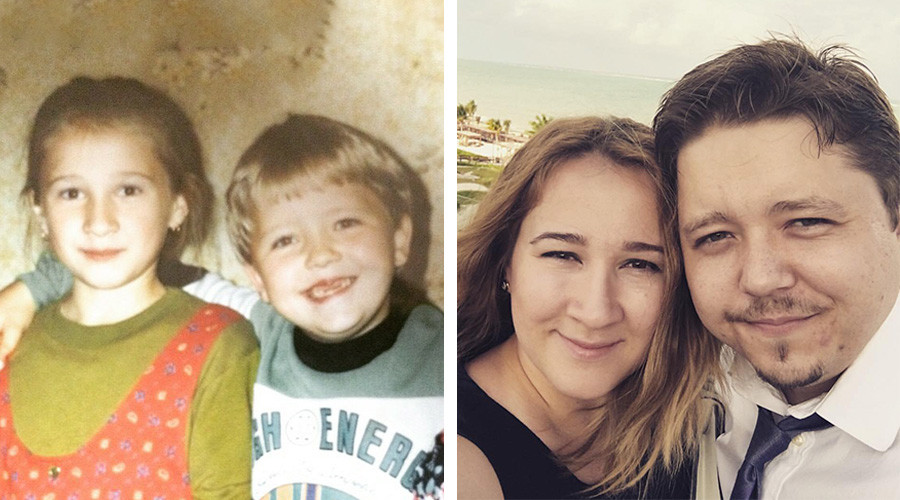

Yulia Zhubreva and Alex Nazarov, then and now

Personal archiveYulia Zhubreva and Alexey Nazarov are in their early thirties, and have known each other since childhood in Moscow. Their mothers were friends in college, but Alexey’s family left for the United States when he was just 8 years old and settled in suburban New Jersey. However, the kids stayed in touch, and eventually, the childhood friendship led to courtship and to marriage. In 2013, Yulia moved to the United States to join her husband.

“I spent six and a half years there, and I tried my best,” Yulia remembers. “When I left Russia, I was a 27-year-old with a successful career, active social life and I traveled a lot. The dull, never-changing suburban life hit me very hard and it didn’t help that we were just outside New York City or that we went out as much as we could. I was also baffled by how expensive everything was and even more so after our son was born. We constantly had to budget, even though my husband earned a decent salary.”

Yulia tried to start a home-based business, but felt she was being suffocated with taxes, to the extent that it was no longer worth it. She started nagging Alex to move back to Russia three years ago, and finally, they left in the summer of 2019. Alex went in to his work to hand in his notice and was offered a transfer to the company’s Moscow office instead - that was a big bit of luck, which allowed the family to transition more easily into their life in Moscow. Meanwhile, Yulia was able to re-enter the HR industry as a recruiter.

Yulia is most impressed with how much more affordable and convenient life has become, and says she is happy she made the move back before their son started school, so that he can study in Russian schools in the future, without language issues. “For the equivalent of $50 a month, our son is now attending a full-day state-run pre-school just next door, with extra taekwondo and English classes there and we don’t have to take time off to manage his activities,” she says.

Yulia admits that the neverending construction in Moscow is annoying, and that she has concerns related to the environment and air quality in the city. The wintry slush, a dirty mixture of snow with de-icing reagents, does not help, either. Yet, she says it’s better than the “clean, uniform and boring, overpriced suburbia, punctured by areas so bad that you can’t go there. At least, in Moscow we don’t have places where you will definitely be robbed if you went there at night.” She adds that “it’s a huge relief not to have to worry about the bills, not to have to budget every month, to finally be able to afford to travel again.”

Alex Nazarov, who grew up in the US, is less critical of the American way of life. He can see, he says, where his wife is coming from in her critique, but to him, the way of life in the American suburbs is just a way of life as he knows it. He jokes that it was helpful that he stayed at a friend’s apartment in New York City for a few weeks after Yulia left, while working off his notice period. “The crowds, the hustle and bustle - New York City is much more like Moscow, so it helped the transition,” he says.

Alex says he can tell that his wife made arrangements in a way so as to make him feel the most comfortable in Moscow - for example, by renting a “big enough apartment”, in homage to American suburbia’s multi-thousand square foot homes. But repatriation brought a surprise as well: “In the US, I thought I was a hardened Russian. It was only in Russia that I quickly realised, just how American I really am!”

Overall, Alex finds the Russians more sceptical and less upbeat, in their initial reaction to “just about anything.” “They get to the ‘can do’ attitude in the end, but you always have to push through the ‘no’ to get to a ‘yes’!” He feels it is all worth it, though: “In the States, I practically lived in the office. Here, I spend so much more quality time with my family, with our son, on social outings, on travel.”

Oxana Rylbalchenko (left). Sophia and Stephania in a Moscow park (right).

Olga Childs (left), personal archive (right)Oxana Rybalchenko grew up a typical intelligencia child in 1980s Moscow. She attended English language lessons, music lessons and art history classes. Since childhood, she was obsessed with all things German and went on to study German at university. This included two trimesters of study abroad in Germany, followed by a long career in a German company in Moscow, with frequent visits to its German headquarters. By 2005, she was well placed and well paid.

Yet, another passion developed: this time, for all things Latin American. Oxana learned Spanish in her free time and entered into the exciting world of salsa dancing. She started to spend a lot of time in Cuba, taking in the culture and music. Eventually, she married a Cuban man and stayed. Oxana’s husband worked for a foreign Embassy in Havana, and was paid in “convertible pesos”, Cuba’s currency for foreigners, affording a good lifestyle, even at the time when the country’s economy was disintegrating. The couple lived in a substantial home, and had the use of an Embassy car.

Having heard much praise for Cuban medicine before, Oxana was not impressed when Sophia was born in Havana in 2008. She travelled back to Moscow for the birth of Stephania two years later. Other than that, however, she says life was good. She focused on the children and could easily afford not to work. But it all ended the day her husband was laid off from the Embassy after 15 years of service. In an instant, living in Cuba stopped making sense.

The family had some savings and decided to invest them into a property in Valencia, Spain. They figured at least they all spoke the language and the summer heat on the coast of Spain resembled Cuban climate quite well. Oxana bought a modest apartment and moved there with the girls, just in time for Sophia to start school. With the housing problem solved, she began making a decent living with private tutoring - language lessons in English, German and Russian (popular among expats). The fatal flaw in the plan emerged when her Cuban husband was denied entry into Spain - having already moved the girls, Oxana was left to run the household alone.

It was during her years in Spain, Oxana says, that she finally realised that the idea that she simply had to live abroad was flawed from the get-go. “In Moscow, I was just another ordinary Muscovite. Everyone I knew grew up going to museums and graduating from college. In Valencia, the place I could afford to buy into was not awful - but it was working class. I felt like an alien; not an immigrant, but an actual alien,” she jokes. “From space!” Her neighbors’ concerns revolved around competition for cashiering jobs at a new local supermarket. Everyone around was barely making ends meet.

As a tutor herself, the most distressing to Oxana was the local school. “Spain is a country rich with culture and tradition, yet, the curriculum was stripped down to bare minimum, they were teaching nothing. The school itself looked and felt like a shack.” She joined the Facebook page of a local school for her parent’s address in Moscow, and the conditions, the children and the activities she saw there filled her with envy. She began making the commute to the Russian Embassy’s external learning center in Madrid, in order for her girls to keep up with Russian curriculum. In the end, Oxana lasted 4 years in Spain, and says that the hardest part was admitting to herself that she had made a mistake. She still hasn’t managed to sell the apartment in Valencia, either.

When she finally came back to Moscow with the girls, then aged 10 and almost 8, in the summer of 2018, things magically fell into place. The neighborhood public school that she had been observing enviously on social media, turned out to be a specialist Spanish language immersion school, with an optional IB program taught in Spanish for a modest fee. The girls joined the local music school, where Sophia plays the guitar and Stephania the flute - she’s showing promise and is now slated for a conservatory. Sophia, who is interested in biology, attends an enrichment science program.

Oxana says she used to worry about the girls’ future in Moscow because of their dark skin - their Cuban father is black. These fears, she says, dissipated instantly - she quickly forgot it was even a thing. But her husband, who had stayed with the family in Moscow before, speaks no Russian and was unable to find any use for his skills here. Has all this wandering put too much stress on their marriage? Oxana holds up her hand. “The ring is still on my finger,” she says.

Oxana decided not to return to a career. In Moscow, her tutoring income is sufficient for a comfortable lifestyle that allows her to focus on the children, and all of their education and activities, except the extra IB program payment, are free: “Sophia asks me all the time - mom, why were we in Spain? I do not have an answer. But I blame the Iron Curtain. We grew up thinking that the grass was greener on the other side, but if we could go and see for ourselves that it was not, our generation would not be so focused on leaving.”

Editor's note: This article was amended on Feb. 18, 2020 to include minor changes in language.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox