“This country was working wonders. Lloyd had found himself here,” wrote Margaret Glascoe about her son, Lloyd Patterson, who fled the U.S. for the Soviet Union in the 1930s. Despite Russia being in the midst of Stalin’s great purge, it still turned out to be a safer place for him. At least there was no Ku Klux Klan lynch.

Lloyd Patterson was a grandson of a slave. He studied scenic design at a theatrical college for black people in Virginia, but it had to close after a student strike and a scandal with their teacher, who had been noticed in the ranks of the Ku Klux Klan.

By accident, Lloyd saw an advertisement saying Soviet Russia needed a group of young black people for a movie production. In 1932, seeking racial equality, job opportunities and simply a better life, Lloyd traveled to the Soviet Union with several other black Americans.

Lloyd Patterson (third row, second from the right) and colleagues head to Moscow

Courtesy of James L.PattersonPatterson started working as an artist for the Soviet movie called Black and White that was supposed to denounce American racism. The project was eventually canceled, but Lloyd remained in the Soviet Union, learned Russian and married a Soviet fashion designer named Vera Aralova. So, in a strange way, the problem of racism actually helped him arrange his life.

Lloyd and Vera had three kids and he kept working as an artist and an interior designer. Finally, Lloyd found himself as a radio host, one of those pioneering the Soviet English-speaking broadcasting. Subsequently, his radio career advanced quickly.

Vera Aralova Patterson with her sons James (L) and Tom

Courtesy of James L.PattersonWhen World War II began, Vera and the kids were evacuated to Siberia, while Lloyd remained in Moscow. During a bomb attack he was injured and evacuated to the Urals and then to the Far East. However, in 1942, exactly ten years after he had moved to the USSR, he died, due to complications from injuries.

My father abandoned his homeland

where he had endured

The bitter insult of so many things denied.

My father the lefty

fought the Great Patriotic War

For the Soviet Fatherland

my father died.

That’s a fragment of the poem, written by James Patterson, one of Lloyed’s sons. To be accurate, his name was James Lloydovich Patterson, which means James - son of Lloyd - Patterson. A full name includes a patronymic in Russian.

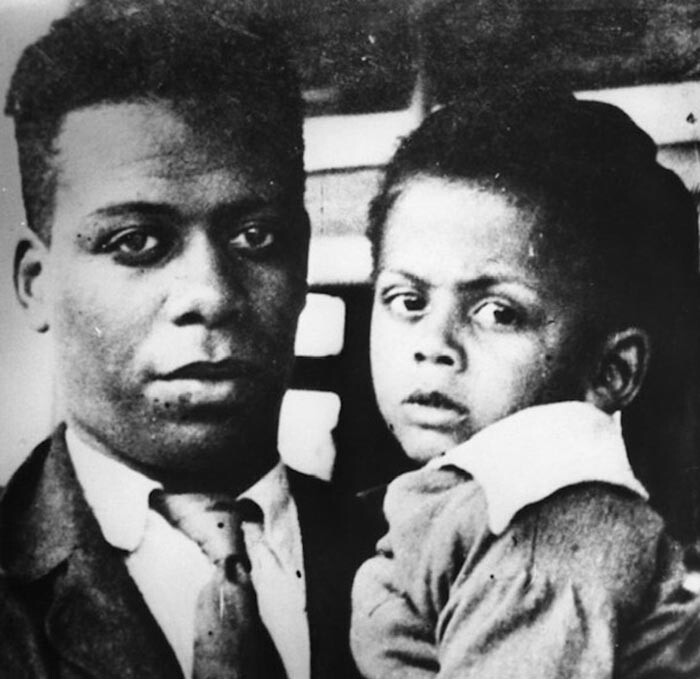

Lloyd Patterson and his son James

Courtesy of James L.PattersonJames, a rare “example” of a mixed Russian-African American couple’s child, was born in 1933. When he was only three, he starred in the Soviet movie titled ‘Circus’ (1936), becoming the most famous black child actor in Russian history.

The movie praised the virtues of Soviet racial tolerance. According to the plot, after giving birth to a black baby, an American circus artist suffers from racism. As a guest performer, she travels to Soviet Moscow where she finds not only refuge, but happiness and love. The scene shows how her little black son is warmly welcomed in the Soviet country.

A still from Circus movie featuring James and his film mother, actress Lyubov Orlova, 1936

P. Minev/SputnikThough the movie became incredibly popular in the USSR, bringing fame to James, he didn’t continue his acting career. Patterson-Jr. dreamt of sea, so he graduated from the prestigious Nakhimov military academy. He became a submarine officer and wrote poems as a pastime.

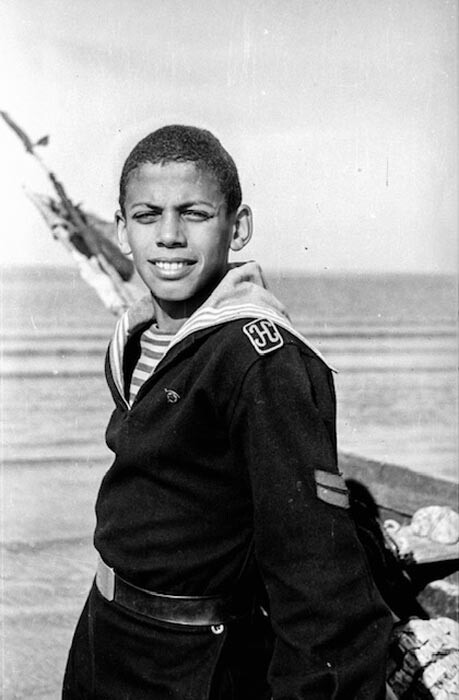

James as a navy school student

Courtesy of James L.PattersonAfter publishing his first collection of poems called ‘Russia. Africa’ in 1963, James decided to give up military service and enrolled in the Gorky Literature Institute. So he became a Soviet poet, a member of the Soviet Union of Writers and a regular contributor to the literary magazines.

James Patterson talking with students a school in the city of Petropavlovsk-Kamchatsky

A.Vlasov/SputnikHe traveled around Russia performing his poems - and even installed the honorary plaque commemorating his father in the Far Eastern city of Komsomolsk-on-Amur.

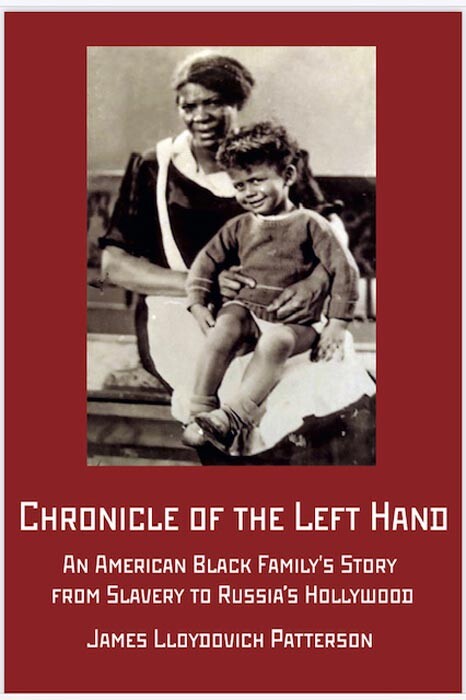

In 1964, James Patterson decided to publish ‘Chronicles of the Left Hand’, the memoirs of his grandmother, Margaret Glascoe, which we quoted an excerpt from in the beginning.

On a book cover, James Patterson is featured with his grandmother Margaret Glascoe in Moscow, 1935

Courtesy of James L.Patterson / New Academia PublishingMargaret Glascoe was the daughter of a black man named Patrick Hager. He was a bastard son of a plantation landowner and was also a victim of slavery. As a baby, he miraculously survived after the landowner’s wife threw him into fire (though he severely injured his right hand). Facing the injustice of his rightless position and economical oppression, he didn’t get along with slave life and fought for his rights. Eventually, he managed to buy his own land.

Margaret faced racial segregation, as well, and she worked hard to give her son the education she couldn’t receive. Soon after, her son Lloyd relocated to the USSR, Margaret joined him - and worked for several years in an auto parts factory in Russia.

Supplying his grandmother’s memoirs with his own comments, James Patterson then published a book in Russian.

Fast forward to contemporary times. During the Covid-19 pandemic, Amy Ballard, a retiree of the Smithsonian Institution in Washington D.C., found an article in the Los Angeles Review of Books entitled: ‘The Only One Left: A Conversation with James Lloydovich Patterson about Grigori Aleksandrov’s Circus’. She recalled that, years ago, she attended a lecture about black Americans who had moved to the Soviet Union, where his name was also mentioned.

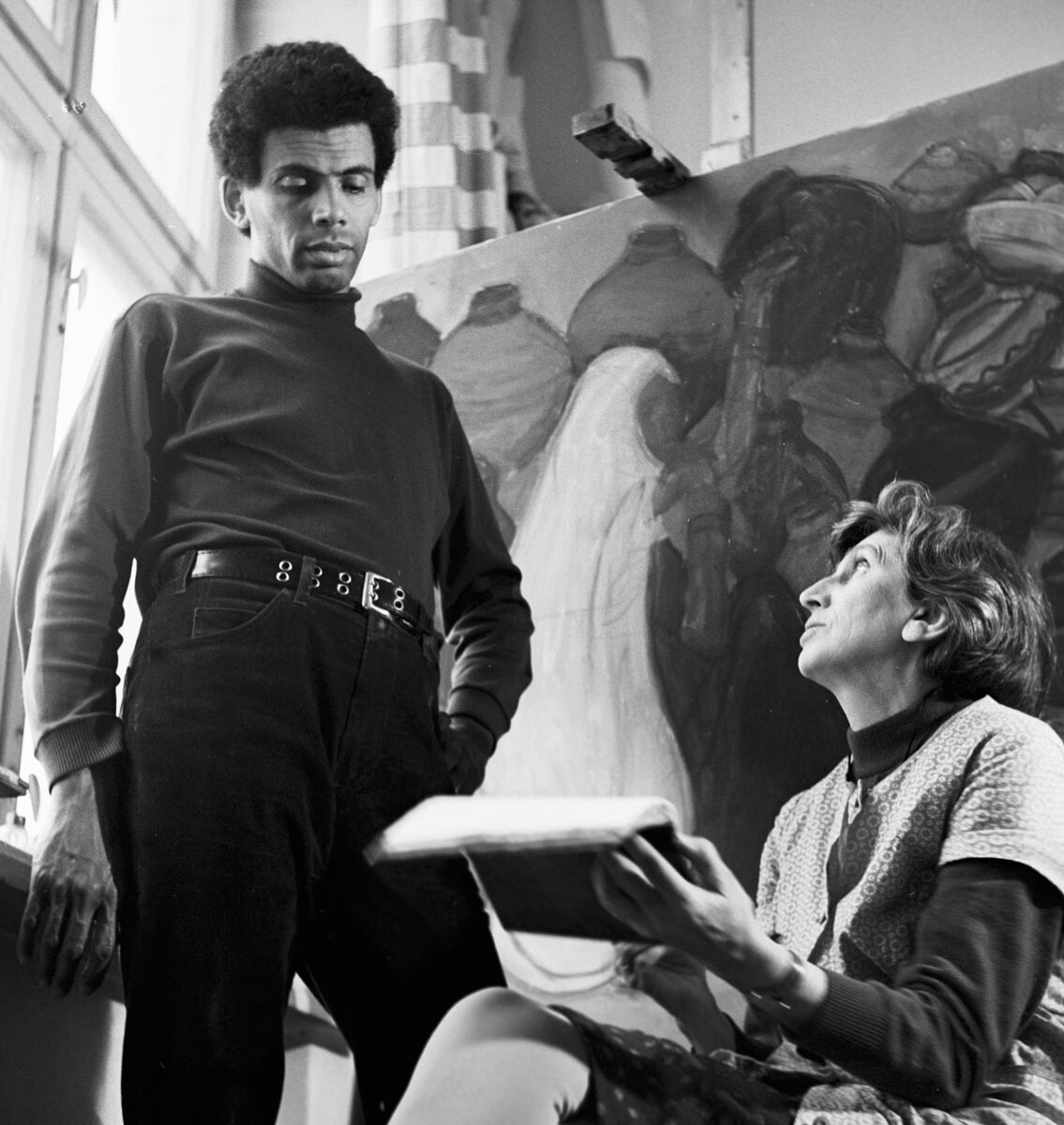

James Patterson and Vera Aralova

Dmitry Debabov/SputnikShe found out that Mr. Patterson had moved to the U.S. in the 1990s with his mother. After the collapse of the USSR, they were seeking financial stability as a poet and a fashion designer, respectively. She also learnt that Vera Aralova passed away in 2001, already on U.S. soil.

Amy Ballard managed to interview Patterson, who now lives in Washington D.C. “He talked about his mother and father, both of whom he still dearly misses years after their deaths. He also told us that he misses Russian food and good chocolate, which he had gorged on as a little boy,” Amy says.

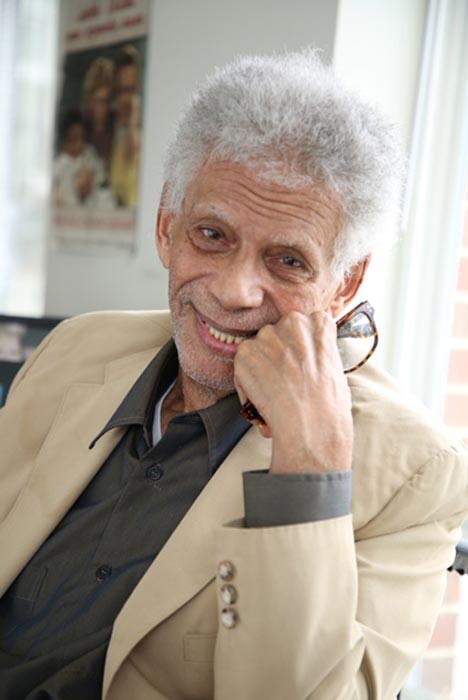

James Patterson in Washington D.C.

Katya Chilingiri BalabanTogether, they poured over piles of his papers, family photos and poems from his time in D.C. “I reflected on the fact that though Mr. Patterson had enjoyed the privilege of being a film star, that experience was born from generational struggles that had played out on U.S. shores,” Amy says.

Eventually Amy Ballard became a coordinator and mastermind of the first ever English translation of Patterson’s grandmother book. With her team of enthusiasts, they arranged translations of the original memoirs, as well as Lloyd Patterson’s handwritten letters to his family. And they’ve added a life story of James Patterson in photos.

‘Chronicle of the Left Hand’ subtitled as “An American Black Family’s Story From Slavery to Russia's Hollywood” was published in 2022 in the U.S. (New Academia Publishing). Shedding light on this untold episode in black American history, the book also portrayed a little known episode in the history of black people in the Soviet Union.

Dear readers,

Our website and social media accounts are under threat of being restricted or banned, due to the current circumstances. So, to keep up with our latest content, simply do the following:

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox