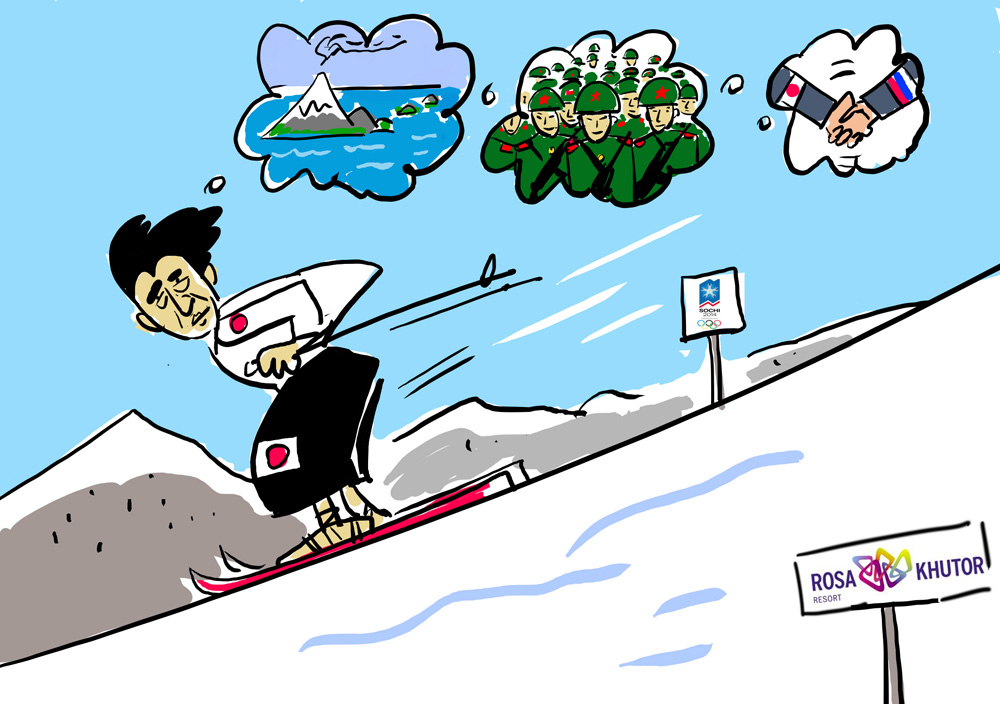

Shinzo Abe last visited Russia for the opening ceremony of the 2014 Winter Olympics in Sochi. The visit, which took place amidst an informal boycott from Western leaders, demonstrated Tokyo’s special commitment to establish qualitatively new relations with Moscow. The head of the Japanese Cabinet first spoke of a thaw in relations with Russia after the Liberal Democratic Party was voted into power in 2012.

Moscow appreciated Abe’s gesture of visiting Sochi in 2014, but could not follow through on it because just a few days later the acute phase of the Ukrainian political crisis began, leading to a regime change in Kiev and a jurisdiction change in Crimea.

Then there was the exclusion of Russia from the G8, the sanctions and the escalation in Ukraine.

For Tokyo, these events were especially inappropriate. When it comes to Japan’s political priorities, the situation in East Asia and the Pacific in general takes center stage. Tokyo wants the balance of power shifted in Asia because of the growth of China and all the developments around the North Korean nuclear missile program. In both cases the role of Russia is very noticeable.

The agreement to establish a strategic partnership between Moscow and Beijing (during the May 2015 visit by Xi Jinping) alarmed Tokyo as it pondered over prospect of dealing with a Russia-China alliance. Under these circumstances, full participation in American attempts to isolate Russia was not in Japan's interests.

Abe is still in a difficult position. Japan is allied with the U.S., which guarantees the former’s safety, including from China. Tokyo has maneuvered as best as it could. The sanctions Japan introduced against Russia were moderate and more symbolic than essential. An unwillingness to run ahead of the locomotive of anti-Russia sentiment was compensated by Japan's attention to Kiev. Japan emphasized how it cared about the fate of Ukraine.

Even at the peak of tensions in 2014 and early 2015, the Japanese government avoided statements about the cancellation of the visit of Vladimir Putin, which was discussed before the events in Kiev. It was clear that by welcoming the Russian President, Japan would trigger a tsunami from Washington.

A couple of months ago ubiquitous reports suggested that Shinzo Abe allegedly turned down a strong request from Barack Obama to not visit Russia.

Recently there was another interesting media leak. Last year German Chancellor Angela Merkel allegedly invited Japan to join NATO, but he declined the offer for fear of Russia's reaction.

If this is true, then the idea is very strange. It is unclear why the North Atlantic Alliance needs a Pacific Japan, and, therefore, the obligation to participate in a potential armed conflict in the region (most likely, not with Russia, but with China). And it's unclear what Tokyo's formal involvement in the unit would achieve, especially since the United States guarantees Japan’s security under a treaty.

Abe is keeping Japanese national interests in mind by visiting Sochi. After all, the Japanese Prime Minister is not visiting Russia because of a shift in Tokyo’s foreign policy towards Moscow, but because he is convinced of the exceptional importance of Sino-Russian relations in the long term.

For Moscow, Tokyo also has a special significance, and the efforts of the Japanese Prime Minister should be appreciated. Russia has just started developing a new long-term strategy for its relations in Asia, and to focus exclusively on China is wrong. Russia needs maximum diversification, and a country as economically and politically influential as Japan is extremely important.

Japan is one of the main practitioners of a new model of international relations.

Old alliances are not disappearing but the concept of blocs with hard binding relationships does not correspond with the interdependent and closely intertwined world of the 21st century. The ability to diversify relations and to build ties with the largest possible number of appropriate partners is a quality valued by many countries. In this sense, Japan's efforts for the preservation of balance can be seen as the nascent model.

This does not mean a lack of prioritization It's hard to imagine a situation in which strategic ties with the U.S. will cease to be Japan's topmost priority. But priority is not a rejection of productive relationships with other important partners. The same applies to Russia - the priority of relations with China will never be equal to their exclusivity.

Russia and Japan face a major challenge when it comes to diplomatic relations. There is the question of the Southern Kuril Islands. Breakthroughs will not happen on the territorial dispute when Abe visits Sochi. Here the priorities are still not the same, even if both parties have a sincere desire to move ahead.

First published in Russian by Rossiyskaya Gazeta

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox