Forshmak - the official Jewish contribution to Soviet cooking

Forshmak.

Anna KharzeevaThis piece is part of the Soviet Diet Cookbook, a blog about a modern Russian girl cooking Soviet food. To read more of the series, click here.

“It’s terrible! Sounds disgusting!” I exclaim, reading the recipe for forshmak to Granny.

She’s at home and has everything ready to make tsimes, a traditional Ashkenazi stew of vegetables and dried fruit, so I’m holding her up. I myself already have forshmak in the oven – the only thing missing now is some klezmer music in the background.

I think the recipe for forshmak is the only Jewish recipe in the Book – and, indeed, it doesn’t sound all that appetizing: grind fried or boiled meat with herring and add potatoes and sour cream. “Why would you ever combine herring and meat?” I ask, and Granny and I burst out laughing for a good minute. “Don’t add the herring,” she says. “It’s disgusting.” I don’t need to be told twice.

My version of forshmak – following the Book’s recipe to the letter but omitting the herring – is absolutely delicious. Not haute cuisine, but comfort food delicious. I’m not sure I would serve it as a hot starter as suggested in the Book – I would just fill a huge bowl with it, crawl on the couch and emerge 2 hours and 5 kilos later.

Often when I ask Granny about Soviet recipes, she says, “we made a Jewish version of this soup,” or “you know, we mostly cooked Jewish food.” But I wondered how widespread Jewish cuisine was outside our home. These days, Israeli falafel has taken Moscow by storm. But what about Ashkenazi recipes in the Soviet times?

“Soviet Jews kept their Jewish diet. They would get their meat butchered at special Jewish butchers – we saw Jewish women carrying chickens to the butchers from the market in Odessa,” Granny told me. “My mom never made ‘herring under a fur coat,’ but her signature dish was marinated herring – everyone who came over always knew there would be marinated herring, and they loved it. But this cuisine didn’t spread outside the homes of Jewish families.

“One Ashkenazi meal however made it into Russian language – tsimes [Russians will say ‘that’s the tsimes of it,’ meaning this is the ‘flavor’ of the story]. People say it and misuse it all the time without knowing what it actually means. When I tell them, they’re always very surprised.”

Jewish challah was available and called challah until the ”fight with cosmopolitism” in 1948, when having a Jewish name wasn’t appropriate anymore, and challah had to go by the unimaginative name of “pletyonka” (twist). My great-grandmother had to undergo a name change, too. When she became a schoolteacher in 1950, the director of the school told her the name Munya Izrailevna was too Jewish and no good, so she became Maria Isaevna. She was Munya Izralievna at home, Maria Izrailevna to the neighbors, and Maria Isaevna at schools – “she was encoded,” laughs Granny.

There was never any forshmak in our family it seems – marinated herring is the closest thing my great-grandmother made for the people who called her Munya Izrailevna.

Granny wasn’t allowed to study to become an architect because of her ethnicity, and her options for a job as a programmer were “80 percent slimmer than others,” according to my grandfather’s high-up-in-the-Party friend. But hey, Jews got a recipe in the Soviet cookbook (a dubious one, yes, but it’s there nevertheless). And, for what it’s worth I’ll take it – after all, it made me laugh, it’s delicious after slight adjustment and goes well with klezmer.

Forshmak

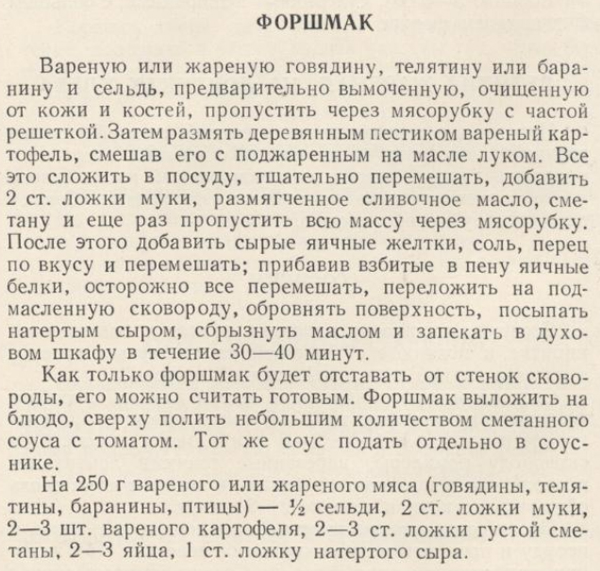

The recipe from the Soviet Cook Book, page 72

The recipe from the Soviet Cook Book, page 72

Ingridients:

250 g fried or boiled meat (beef, veal, lamb, poultry); ½ herring; 2 Tbsp flour; 2-3 boiled potatoes; 2-3 Tbsp sour cream; 2-3 eggs; 1 Tbsp grated cheese

Mince the meat with the herring, which has been pre-soaked and cleaned of skin and bones. Knead with a wooden pestle the boiled potatoes, mixed with fried onions in butter. Put all this into a bowl and mix well. Add the flour, softened butter and sour cream. Mix well and put the whole mass through a meat grinder.

After that, add the raw egg yolks, salt, pepper to taste and mix well. Then fold in frothed egg whites, sprinkle with grated cheese, drizzle with butter and bake in the oven for 30-40 minutes. Once the mixture pulls away from the walls of the pan, it can be considered ready.

Put the forshmak on a plate and pour over it a small amount of cream sauce with tomatoes. The same sauce can be served on the side in a gravy boat.

Read more: Makarony po-flotsky - the meal the sustained the Russian Navy>>>

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox