At the beginning of the 20th century, the Russian chemist and photographer Sergei Prokudin-Gorsky devised a complex process for vivid, detailed color photography (see box text below). His vision of photography as a form of education and enlightenment was demonstrated with special clarity through his photographs of architectural monuments in the historic sites throughout the Russian heartland.

Transportation, which was particularly interested in photographs along Russia’s rail and waterways. One of the most important of these was the Mariinsky Waterway, which connected St. Petersburg via the Sheksna River with the Volga River Basin.

William Brumfield

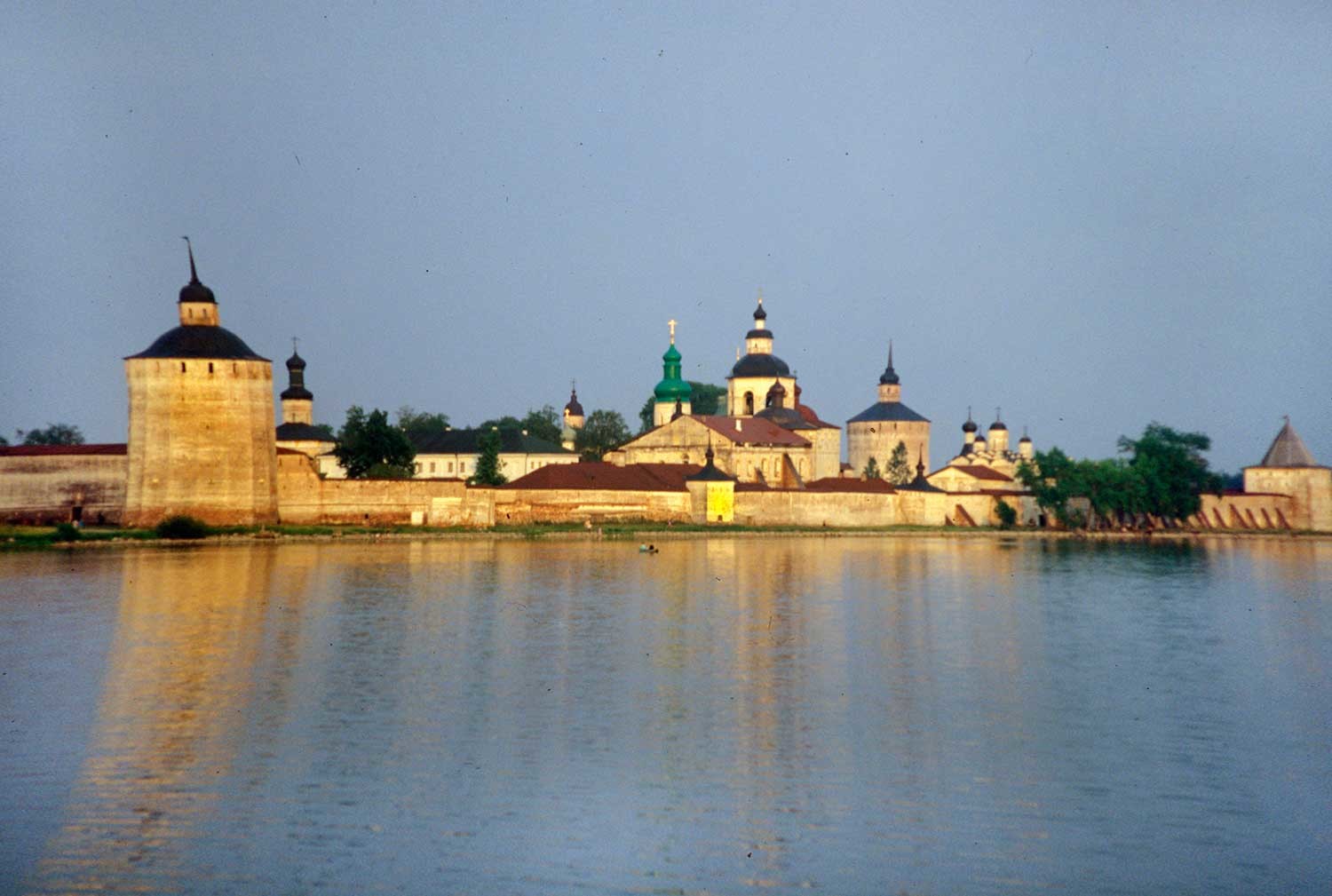

In the summer of 1909, Prokudin-Gorsky traveled along this waterway and visited historic settlements in northern Russia, including the small town of Kirillov, site of the St. Kirill Belozerskii Monastery. With its massive walls, brick towers and array of churches, this monastery was one of the most impressive sights in the Russian North. Its location, on Siverskoe Lake near the Sheksna River, was both picturesque and strategically important. Prokudin-Gorsky photographed the monastery from the south shore of the lake. My photographs from the lake in the late 1990s show little change in its appearance.

Sergei Prokudin-Gorsky

A distinguished history

With the revival of monasticism in Moscow during the 14th century under the direction of St. Sergius of Radonezh, pioneer monks sought remote northern areas as a test of their ascetic faith and dedication. At the same time, Muscovite princes supported their efforts, which not only spread the Orthodox faith but also consolidated Moscow's territorial expansion into the rich forests of the far north.

William Brumfield

The origins of this monastery date to 1397, when the monk Kirill (Cyril) of Belozersk (1337-1427) arrived at Siverskoe Lake and dug a cave dwelling for himself. Kirill had taken monastic vows in Moscow’s powerful Simonov Monastery and became of disciple of St. Sergius, who supported his determination. Inspired by a vision of the Virgin Mary, he made his way to the region of Beloe Ozero (White Lake) and from there to Siverskoe Lake.

Kirill was joined by the monk Ferapont, who the following year founded a monastic community on nearby Lake Borodavo. The nucleus of the monastery rapidly formed, and Kirill dedicated it to the revered Dormition of Mary, Mother of God. Kirill was canonized by the Russian Orthodox Church in 1547.

William Brumfield

In the turbulent early 15th century the St. Kirill Dormition Monastery played a significant role in maintaining Moscow’s dynastic stability. Consequently, the monastery received donations that had made it one of the largest in Muscovy by the 16th century, second in size to the Trinity-St. Sergius Monastery near Moscow.

As usual in medieval Russia, the original monastery was built of logs. The monastery’s first structure to be built of brick and stone was the Dormition Cathedral, begun in 1496 and expanded with small attached churches over the next two centuries.

Sergei Prokudin-Gorsky

A major patron of the monastery was Basil III (1479-1533), grand prince of Moscow, who in 1528 made a pilgrimage to the monastery with his second wife, Elena Glinskaia, to pray for the birth of a son and heir. Basil subsequently sponsored two brick churches in the monastery, including the Church of the Decapitation of John the Baptist, which became the nucleus of another monastery. The dedication to John the Baptist was no doubt connected with the long-anticipated birth of his son Ivan (John) in 1530.

As a result, the monastery founded by St. Kirill came to consist of two monasteries — one dedicated to the Dormition and the other, to John the Baptist — as well as a settlement for lay workers protected by a system of walls. At the beginning of the 17th century, these walls enabled the monastery to defend the area against marauders during a period of widespread civil unrest and foreign invasion known as the “Time of Troubles.”

William Brumfield

A fortress never attacked

A major surge in the monastery's fortunes occurred in the second half of the 17th century, when Tsar Alexis Mikhailovich decided to rebuild the monastery as an impregnable bulwark for Moscow's vital northern domains. At that time, the most likely enemy was Sweden, which had already gained considerable territory held in medieval times by the Russian city-state of Novgorod. If Sweden attempted a deep invasion, the St. Kirill Monastery would stand as a firm obstacle.

In 1653, Alexis decreed the expansion of the monastery’s walls and towers, which rose over a period of several decades in the latter part of the 17th century. Prokudin-Gorsky photographed one of the most impressive segments of the wall, as did I a century later.

William Brumfield

Fortunately, no hostile army ever came close to the citadel that had been expanded at such great effort. Its walls and towers serve as a monument to the Russian ability to erect masonry structures of enormous extent during the late medieval period. With victories against the Swedes in the early 18th century and the founding of St. Petersburg (1703), Peter the Great fundamentally altered Russia’s geopolitical position, in effect eliminating the threat to the Russian north. Peter’s new capital, St. Petersburg, would itself become Russia’s surpassing construction project.

The waning importance of the St. Kirill Monastery led to its neglect during the 18th and 19th centuries. In the late 19th century a revival of interest in Russia’s medieval heritage led to restoration efforts that continued during the early Soviet period. In 1924, the first museum was established in the monastery. The onslaught of ideological repression in the 1930s undercut much of this work and led to material losses, such as the melting down of the monastery's remarkable bell ensemble.

Only after World War II did the museum within the St. Kirill Belozerskii Monastery revive its cultural potential. This museum and the monastery territory have become a major repository of Russian cultural treasures, and there are many signs of progress. The museum now has an excellent gallery of historic religious art. Part of the monastery has reverted to the use of the Orthodox Church. In 2017, the monastery celebrated its 620th anniversary, a mark of its enduring importance in Russian history.

William Brumfield

In the early 20th century the Russian photographer Sergei Prokudin-Gorsky devised a complex process for color photography. Between 1903 and 1916 he traveled through the Russian Empire and took over 2,000 photographs with the process, which involved three exposures on a glass plate. In August 1918, he left Russia with a large part of his collection of glass negatives and ultimately resettled in France. After his death in Paris in 1944, his heirs sold his collection to the Library of Congress. In the early 21st century the Library digitized the Prokudin-Gorsky Collection and made it freely available to the global public. A number of Russian websites now have versions of the collection. In 1986 the architectural historian and photographer William Brumfield organized the first exhibit of Prokudin-Gorsky photographs at the Library of Congress. Over a period of work in Russia beginning in 1970, Brumfield has photographed most of the sites visited by Prokudin-Gorsky. This series of articles will juxtapose Prokudin-Gorsky’s views of architectural monuments with photographs taken by Brumfield decades later.