The Caucasus Mountains are one of the most picturesque places in Russia, which attracts extreme athletes, as well as nature enthusiasts. Apart from tourism, the Caucasus Mountains are also notable for their natural resources. In the early Soviet years, deposits of various ores and rare metals were found, which spawned the mass construction of factories and settlements for workers. Many such places, however, did not survive the crisis of the 1990s (check out our previous report on the ghost mining village of Sadon in North Ossetia here). And now, let’s take a walk around the highest mountain town in Russia, Tyrnyauz.

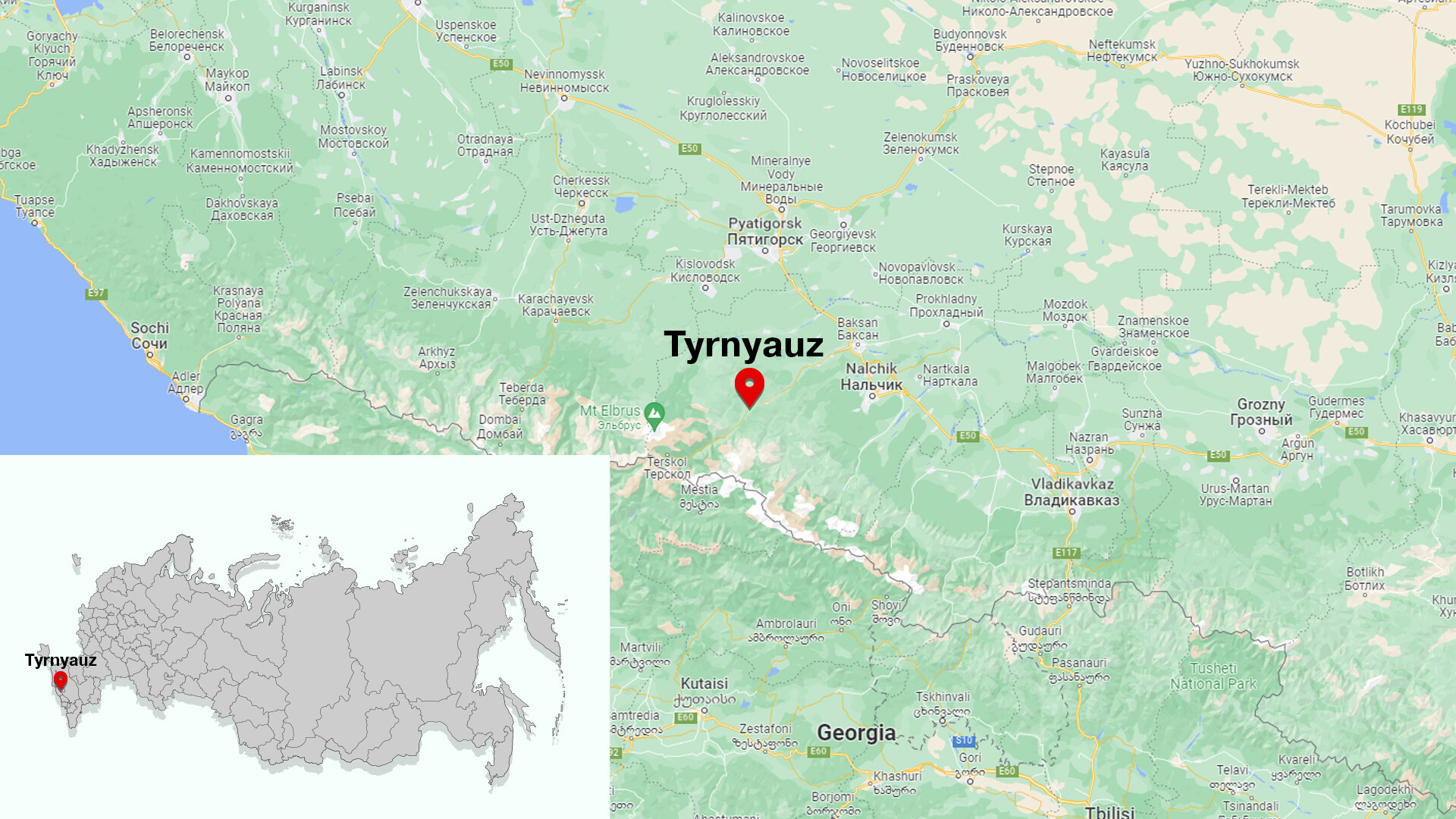

The town of Tyrnyauz is just 80 km from Nalchik, the capital of the Republic of Kabardino-Balkaria, along a highway that leads to Mount Elbrus. Tyrnyauz is situated 1,300 meters above sea level, but some districts of the town are even higher. According to various estimates, it’s between 1,500-2,000 meters above sea level.

In 1934, a deposit of the rare earth metals of wolfram and molybdenum was discovered in this area. Over the next few years, mines and processing plants were opened there. The first output was produced in 1939, but, in 1942, the plant had to be destroyed, as Nazi Germany was invading the Caucasus. Wolfram was essential, among other things, for military purposes and the Soviet leadership didn’t want the metal to get in the hands of the enemy.

Right after the end of the Great Patriotic War in 1945, the plant was restored. People from all over the Soviet Union arrived to work there. The miners’ settlement was quickly growing and, in 1955, Tyrnyauz received the status of the town. While, in 1939, there were 3,500 people living there, in 1959, there were almost 13,000.

The architecture of the town looks no different from any other Soviet locality: typical panel and brick standard houses painted in green, pink and white. But they all look absolutely fantastic against the background of the mountainous landscape.

By the collapse of the USSR, the city was home to more than 30,000 people, most of whom were employed in mining and processing of wolframium and molybdenum. However, due to the 1990s economic crisis, the company stopped receiving new orders and eventually went bankrupt in 2001.

The mines were not appropriately maintained, the structures were simply abandoned and the metal parts and equipment were scrapped. Thus, all that was left of the once prosperous town was a memory.

Former miners left the town, selling their apartments for cheap to the residents of the surrounding villages. Today, about 20,000 people reside there. Many go to work in the tourist mountain villages.

But, the town has more than just economic problems. Tyrnyauz stretches along the Baksan River. The name of this river is translated from Kabardinian as ‘foaming’ or ‘flooding’. A little higher up, the road is often blocked by mudflows. They occur there almost every summer, but the mudflow in the year 2000 was especially strong. At that time, eight people were killed and another 40 went missing. The force of the flow caused buildings to collapse as if they were cardboard. More than 900 people were left homeless.

“I lived in Tyrnyauz from 1987 to 1996, my grandfather worked at this mine,” writes former resident Alexander Yakovlev. “When we left, the apartment was sealed up and, now, strangers live there who have their homes covered with mud. I don’t feel bad, let them live there. I regret that a once-prosperous town was turned into a dump and there’s such ruin and poverty there.”

Over time, the town fell into disrepair, but, a few years ago, it was decided to rebuild the plant.

In 2021, the construction of a renewed plant was launched at the Tyrnyauz deposit. The ‘Elbrusmetal’ plant promises to open in 2023 and reach full capacity by 2026. The project is expected to create 800 new jobs. Tyrnyauz has the largest deposit, about 40% of the country’s reserves.

Dear readers,

Our website and social media accounts are under threat of being restricted or banned, due to the current circumstances. So, to keep up with our latest content, simply do the following:

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox