Literary scholars tend to believe that many 20th-century dystopias are inspired by Fyodor Dostoevsky's 1864 novel ‘Notes from Underground’ and its anti-hero with his distorted ideas about social order and morality.

And yet, dystopia as a genre in Russian literature began to be discussed after the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution. It was it as a turning point in history that gave a powerful creative impulse to many intelligentsia writers. In their fantasies, this upheaval is akin to the apocalypse, on the wreckage of which a new world and new laws of life are built.

Interest in dystopias developed in waves. In Soviet times, they were banned, because, in essence, they were a satire of the Bolshevik system. Nevertheless, they appeared now and then in the unofficial press - ‘samizdat’ (lit. ‘self-publishers’) and also published in the West. During perestroika, a huge amount of previously banned literature and non-fiction about the Gulag appeared in Russia, as well - more powerful than any dystopia.

Another new round of interest occurred in the 2000s, also due to the development of technology. And it hasn't stopped until now. We highlight five major Soviet and Russian works in this genre.

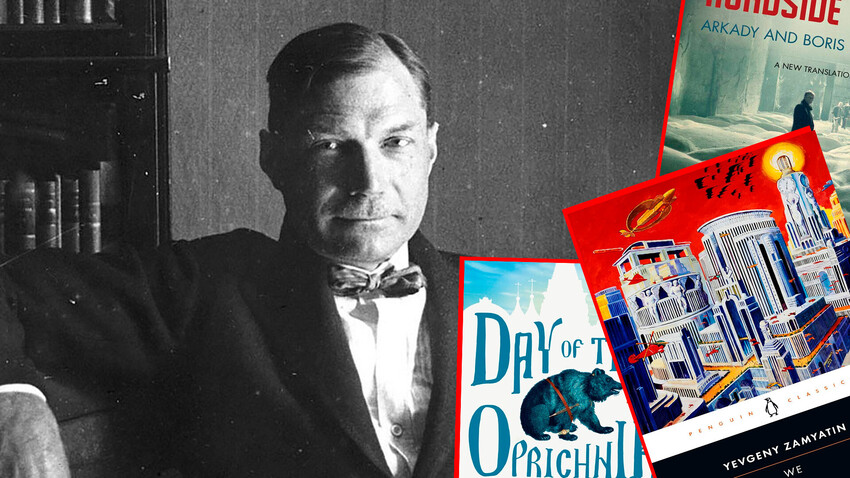

It is no exaggeration to say that this is considered by many to be the main Russian dystopia. Zamyatin and his satirical novel on the Bolshevik system influenced Orwell himself. It was after reading this novel that he wrote his iconic ‘1984’.

‘We’ describes a totalitarian state reminiscent of military communism, where human life, even intimate life, is under the control of the authorities and people are assigned ordinal numbers instead of names. The book was first published in the West and banned in the USSR until 1988. The author, meanwhile, was arrested, but soon released, thanks to numerous petitions from influential friends. Zamyatin was then allowed to leave the country in the early 1930s.

Platonov's story is a harsh satire on the USSR with its planned economy, the first five-year plan and large socialist construction sites. In the story, the main protagonist participates in digging a pit for a future, all-proletarian house. However, construction does not go beyond the excavation. The bosses talk a lot and do little. Human life is worthless and everything is laid on the altar of some ghostly universal well-being. At the same time, the workers suffer from lack of meaning in life and slowly burn out. The pit they endlessly dig becomes an allegory of their mass grave.

Platonov has a deliberately complex language, which also came with the new reality. The theme of the new language (the “newspeak” as Orwell called it) is generally one of the signs of dystopias.

The plot of this sci-fi dystopia takes place in a fictional town. Several years before the events described in the book, an alien civilization or essence visited Earth. After that several ‘Zones’ appear on the planet, i.e. areas where abnormal physical phenomena occur and where unidentified objects exist. It is forbidden to penetrate the ‘Zones’, but there are “stalkers” who do go into this strange space in search of happiness and the meaning of life.

This is one of Strugatsky's most popular novels and Andrei Tarkovsky based his movie ‘Stalker’ (1979) on it.

Granddaughter of famous writer Alexei Tolstoy wrote her first (and only) novel in 1986 after the Chernobyl accident. She manged to complete it only by the beginning of the new millennium. ‘The Slynx’ shows life after the apocalypse, a kind of explosion. The characters are strange, mutated creatures and animals, as well as people, who have lost their former appearance. They have even forgotten their language. And, in the dense forests, there is an unknown creature called ‘Slynx’, who scares everyone by making strange sounds and noises.

Immediately after its release, the novel became a bestseller, generating a wave of both praise and criticism. Tolstaya was accused of combining a mix of successful elements from Strugatsky and Zamyatin.

Sorokin is often called a modern-day prophet. The plots of his novels take place in the “new Middle Ages”, where the standard of living, morality and social order have slipped back to the Dark Ages, with any technological progress pushed back far into the future.

In ‘Day of the Oprichnik’, Sorokin describes the rebirth of Russia after a recent global turmoil in an antient epic style. The year is 2028. In Russia, the monarchy has been restored and the country is separated from the world by ‘The Wall’. The tsar's personal army commits atrocities and repression, strikes fear into the “boyars” and common people, while they live a privileged life, drive expensive cars and go unpunished.

Critics often refer to other dystopias of Sorokin to the “universe” of the ‘Day of the Oprichnik’ :

Dear readers,

Our website and social media accounts are under threat of being restricted or banned, due to the current circumstances. So, to keep up with our latest content, simply do the following:

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox