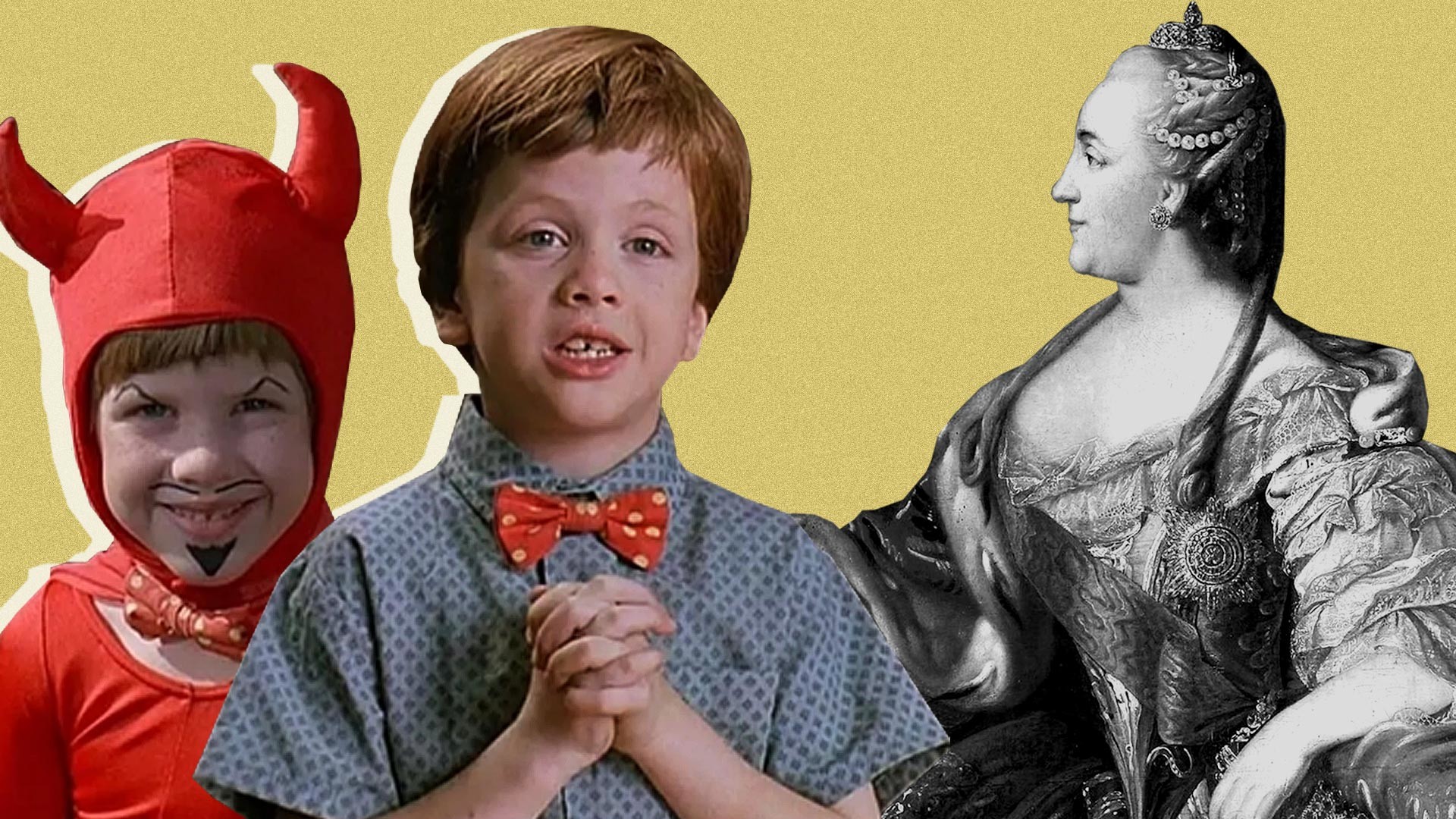

The traditions for bringing up heirs to the throne in Russia had been formed over centuries: Princes were pampered and wrapped in furs, they had up to five meals a day and there was no limit to the amount of sweet things they could eat. Without exception, their nannies and tutors spoke to them gently and never punished them. They had vast amounts of toys and continued to “play” when they grew up - suffice it to recall Peter I’s “Toy Army” of young soldiers.

The young German woman whom we know as Catherine II could exert no influence on the way her son, Emperor Paul I, was brought up. But she noted the regrettable fact that his health and character were flawed and that his upbringing was to blame.

But, when Catherine II became the unchallenged ruler of Russia, she decided to intervene in the upbringing of her favorite grandson (the future Tsar Alexander) and his brother Konstantin. In 1784, the empress issued her own imperial edict: ‘Instructions on the Upbringing of Grand Dukes Alexander and Konstantin’. The most important thing children should acquire was “a proper and clear understanding of things and a healthy body and mind”.

Clothes should be as simple and light as possible. “Let Their Highnesses’ clothing in summer and winter be not too warm, not heavy, not laced up and particularly not too tight in the chest.”

Food should be simple and prepared without spices, with a small amount of salt. If children feel peckish between lunch and dinner, give them a piece of bread and in summer replace one meal with berries or fruit. “They should not eat when full or drink when not thirsty; and they should not be plied with food or drink when full.”

Catherine also recommends that children should not be offered wine unless prescribed by a doctor...

The Empress advises airing the children’s bedroom, especially at night. In winter, their room should not be overheated. The temperature should be no higher than 13-14 degrees on the Réaumur scale (about 16-17 degrees Celsius, or 61-63 Fahrenheit).

And, of course, the children should spend more time outside - “so that in summer and winter Their Highnesses should spend as much time as possible in the open air”.

The empress observes that taking a steam bath and bathing in cold water afterwards has a beneficial effect on children’s health. To prevent colds, she recommends washing their feet in cold water - and in general having no fear that a child might get their feet wet. “In the summer, they should swim as much as they themselves wish, provided they haven’t become sweaty beforehand.”

Catherine’s advice is that children should not sleep on soft feather beds and that their quilts should be light. Their heads should not be wrapped during sleep and they should be put to bed and awakened early. “Between eight and nine hours of sleep seems about right.” The children should be woken up without being startled, but by being quietly called by their name.

Children should not be restricted in their play. “They should be encouraged to engage in exercise and games of all kinds compatible with their age and sex; for exercise confers strength and health on body and mind.” Furthermore, adults should not interfere in children’s games if the children themselves do not ask them to get involved. “Giving children complete freedom to play will make it easier to discover their character and proclivities.”

Do not let children be idle, but do not force them into study either and constantly nourish their curiosity with different activities.

“Do not give them any medicines at all without extreme necessity.” The Empress very progressively and quite appropriately judged that it is better to care for a child’s health than to endlessly give him medicines that would only attract new illnesses. Besides, young constitutions frequently experience chills or fevers. The Empress puts this down to age and believes that these things will pass without the intervention of doctors.

Pain caused by injury, sunburn and that sort of thing is worth treating, of course. But it should be done without haste so that the children learn endurance.

It is a simple rule that a child should be praised for his good behaviour and accomplishments, and for bad behaviour he should be made to feel shame. “No punishment can normally be useful to children if it is not combined with shame at the fact that they have behaved badly.” Children should be motivated to behave well so that they can “win” love and praise.

However much they are punished, they cannot be brought up properly without a personal example. “Carers should not do in front of their wards what they don’t want the children to copy and bad and nefarious examples should altogether be kept out of Their Highnesses’ sight and hearing.”

“Lies and dishonesty should be forbidden both for the children themselves and for those around them and lies should not even be employed in jokes, but, instead, the children should be steered away from lies.”

Children cry for two reasons: 1) from obduracy and 2) sensitivity and a tendency to complain. But neither the one nor the other should be encouraged. Children should not seek to get what they want by employing tears. The children should be taught to “endure what afflicts them with patience and without complaint”.

“From infancy children’s will should be subordinated to common sense and fairness.”

The children should not be struck or berated and, similarly, no-one should be struck or berated in their presence. In addition, they should not be allowed to mistreat animals or insects. Also, teach them to care for what belongs to them, whether it be animals or potted plants.

“The main point of instructing the children should be to instill in them a love for their fellow human beings.”

In infancy, children should be protected from what frightens them - and should not be frightened deliberately. Subsequently, they can be carefully confronted with their fears or an attempt made to turn their fears into a joke.

“Teach children good manners; good manners are based on not holding either oneself or one’s fellow human beings in low esteem,” Catherine wrote.

According to her, four things are completely inimical to good manners:

1) An innate ill breeding which does not view people’s proclivities, physical make-up or condition without a sense of superiority.

2) Disdain and disrespect for people manifested by looks, words, actions and behavior.

3) Condemnation of the actions of fellow human beings through words and mockery, deliberate arguments and constant disagreement.

4) A habit of petty quibbles which always, no matter what, finds an excuse to cavil, condemn and carp; conversely, an excessive show of manners is insufferable in society.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox