“Only in our dreams are we free. The rest of the time we need wages,” English fantasy author Sir Terry Pratchett once famously said, with no hint of irony. It seems like these words of wisdom are no less true in regards to Soviet kids and their childhood dreams.

Some of the Soviet kids’ dreams were hardly practical and pragmatic, but rather associated with the not-too-distant future. Oftentimes, these daily dreams happened to be watered with fear and worry.

“As someone who grew up in the Soviet Union in the 1980s, I was perpetually anxious about the prospect of the nuclear war with the United States, my country’s archenemy,” Natasha, 45, says. “Falling asleep nightly, I seriously dreamed of something that would eradicate the threat and allow me to stop worrying about it, as weird as it may sound. As a child, I perceived the Cold War as a deeply personal, existential threat.”

A group of children holding a placard that says "Nothing is more important than peace."

E.Chechkina/SputnikThe Cuban Missile Crisis was a major confrontation that brought the United States and the Soviet Union to the brink of nuclear war in the early 1960s. Moscow stationed Soviet nuclear missiles in Cuba in response to the deployment of similar-class U.S. missiles in Turkey.

READ MORE: Everything you need to know about the Cold War

This crisis was not the only time when the confrontation between Moscow and Washington reached boiling point. In 1983, the Kremlin was worried about a series of large-scale NATO war games (known as ‘Able Archer 83’), which saw the deployment of tens of thousands of U.S. forces into Europe. In a tit-for-tat exchange, Soviet nuclear forces were immediately placed on high alert to be able to respond to the threat presented by NATO. Luckily, back at the time, the threat turned out to be an exaggeration.

Pretty much like boy scouts in the U.S., Soviet children lived active and vibrant lives. “Soviet childhood is inseparable from summer camping: wake-ups to the sound of the horn, scouting, plenty of contests, fireworks, smearing sleeping kids with toothpaste at night and other escapades,” Tatiana, 47, recalls. “If your parents didn’t send you to summer camp, you just had to stay at your dacha, making tree houses or wreaths of flowers. Winter time was always about skating, skiing, sledging, tossing snowballs, making a snowman. My Soviet childhood days were filled with sports, museums, theaters, reading, watching rare movies. Little time was spent watching TV.”

Artek summer camp in Crimea.

Konstantin Dudchenko/TASSSummer camp was a great way to spend your break off from school, making new friends, perfecting your communication skills, while enjoying some freedom. Soviet children dreamed of spending their holidays at the Artek camp. In the 1970s-1980s, this famous youth camp, located in Crimea along the Black Sea coast, lived up to the core communist values. Nowadays, it still remains a popular resort.

READ MORE: 5 dishes that Soviet kids used to HATE (and grownups still do)

Soviet children spent a lot of time reading, their parents’ cabinets filled with piles of books. And even though Alexandra wasn’t allowed to go to Artek, she was given carte blanche access to all the books found in the house. She chose ‘Karlsson on the Roof’ by Astrid Lindgren. Like many of her peers, she laughed hysterically as she read the best-selling Swedish book about a chubby little man who loved playing tricks on people and said he was the world’s best at everything.

Children walking a dog.

Vsevolod Tarasevich/МАММ/MDFThe book made scores of Soviet kids look up on their roofs to double-check if Karlsson was living there, too. A favorite moment in the book was when the protagonist, Smidge, a seven-year-old boy, finally gets a pet as a birthday present, while Karlson argues: “But I’m better than a dog!” Like Smidge, Alexandra wanted a dog more than anything else in the world. Having a pet was a big responsibility that too many children weren’t prepared for. And yet, if you had a dog, you could walk it five times a day, showing off your treasure to other kids in the neighborhood.

Soviet children wore plain, boring and uncomfortable clothes, mostly made in the USSR. To buy something different was a real problem. Imported clothes were available in stores, but ordinary customers never knew when and where they would be available. “My mom wrote a line number on the palm of her hand and spent hours in line to buy me a pair of Japan-made red leather shoes.” Vera, 39, recalls. “I wore these glamorous shoes only two times before they were stolen from my school locker room. I nearly cried.”

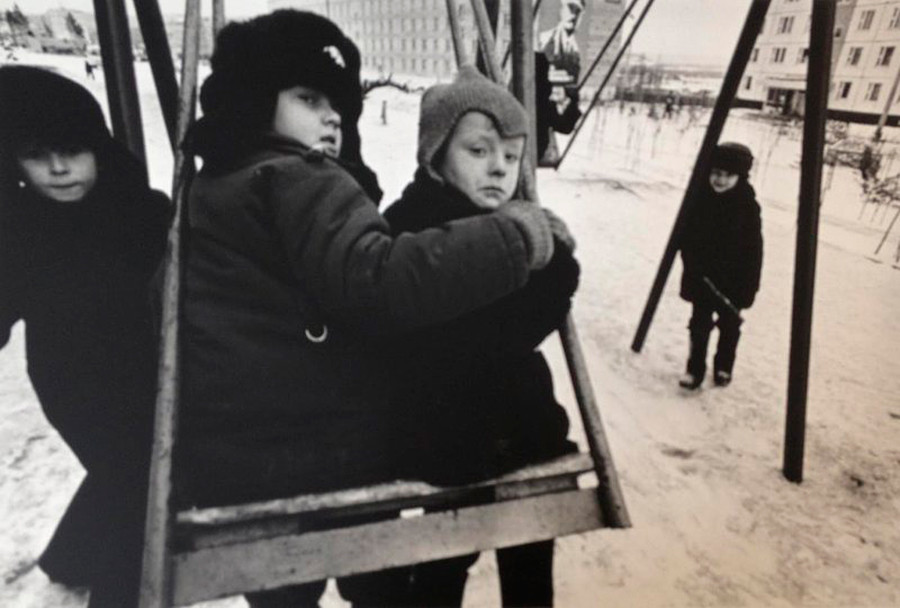

Playing on a swing, 1970.

Valery Schekoldin/МАММ/МDFYears have passed but Dima, 52, still remembers his long Soviet winter coat.

“It was a nightmare, as heavy as a brick. I felt helpless and impotent when I was wearing it,” he said. “I was on cloud nine when my dad brought me a brown coat from Sweden. It had funky yellow sleeves and was as light as a feather.”

“I also remember how much I wanted stylish clothes,” Elena, 40, says. “Something that looked sophisticated.”

READ MORE: This is how 'happy Soviet childhood' looked like (PHOTOS)

“I was a Soviet kid not for too long, but a pretty lucky one, anyway. Being born in Eastern Germany and having lived there for a few years, I got all the pretty clothes and toys one could buy at the time. Not a lot. But the best ones,” Diana recalls.

Some of the children’s parents were allowed to travel abroad. They would come back with a huge variety of gifts, from chewing gums and erasers to backpacks and Barbie dolls.

“A real Barbie doll! I got a Cindy one with a real Barbie head and a fake plastic body, some foreign juice of an unusual color (I tried the bright green kiwi and it was amazing, I still remember how that package looked), potato chips, sodas...”

Those who didn’t have the luxury of going abroad could only dream about ‘La Dolce Vita’.

While some Soviet girls opted for Barbie dolls and trendy clothes, boys preferred electric German train track sets and mopeds. Vadim, 51, was no exception. He says almost every boy in his Soviet childhood had a bicycle. “But a moped was serious stuff, the latest craze, an ultimate dream.”

The trio on a moped.

An archive of Olga KukharDreaming, after all, is a form of planning, so some practical teens would collect glass bottles and bring them to stores for recycling. The empty bottles would fetch some cash, providing enough motivation to collect them. “In the long run, boys got really busy and some even managed to buy themselves a moped in the end.”

Victoria, 41, wanted a moped for a different reason. She was a fan of movies for as long as she can remember. The girl spent her summer holidays in the neighboring Latvia when she happened to watch ‘The Party’ (‘La Boum’), a French comedy starring Sophie Marceau. The movie, which follows a 13-year-old named Vic as she falls in love, falls out of love and continues to live her life to the full, instantly became a classic with Soviet teens. Despite the difference in cultures, it was easy to relate to the movie’s main characters. “I was probably 12 when I watched La Boum. I still remember two things: how Vic had a crush on Mathieu, who drives a moped, and Richard Sanderson’s awesome title song ‘Reality’. It had the words ‘Dreams are my reality. The only kind of real fantasy…’”

A still from La Boum, starring Sophie Marceau.

Claude Pinoteau/Gaumont, Marcel Dassault 1980If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox