This heavy headdress was first mentioned in a 14th century document and dates back to paganism. Horns symbolized fertility, so women could only wear it after the birth of their first child – women predominantly in Tula, Ryazan, Kaluga, Oryol and other southern cities and provinces.

Due to the fact that a kika was not just tall (20-30 centimeters, on average) but also heavy, women had to lift their heads up high to keep it stable. That’s how the Russian word ‘kichitsya’ appeared – to behave arrogantly and walk around with one’s nose in the air.

This ‘kika’ is the spiritual successor to its horned predecessor; it was worn by all married women on holidays.

It’s also considered a very old headdress (the first mention of a hoof-shaped ‘kika’ dates back to 1328); however, it did appear after the Christianization of Russia, so has little in connection with pagan beliefs.

Apart from “hooves”, women also wore ‘kikas’ shaped as pots, shovels and cushions. Usually, all of them were sewn with richly decorated cloth with gold, all hoof-shaped forehead parts were secured with ribbons, strapped around an everyday headdress.

Many historians still can’t arrive at a consensus about what should be considered a ‘soroka’ and what should be considered a ‘kika’, since their different varieties sometimes look practically identical.

However, you definitely won’t mistake a Tula ‘soroka’ for anything else – this headdress literally looks like a bird. It had a front part, “wings” and a back part that was dubbed a tail.

Under the word ‘tail’, they understood colorful ribbons, sewn on like a peacock’s tail; colorful ribbons, meanwhile, were sewn on either sides to create the illusion of wings. Women wore it during the first 2-3 years after marriage on all holidays.

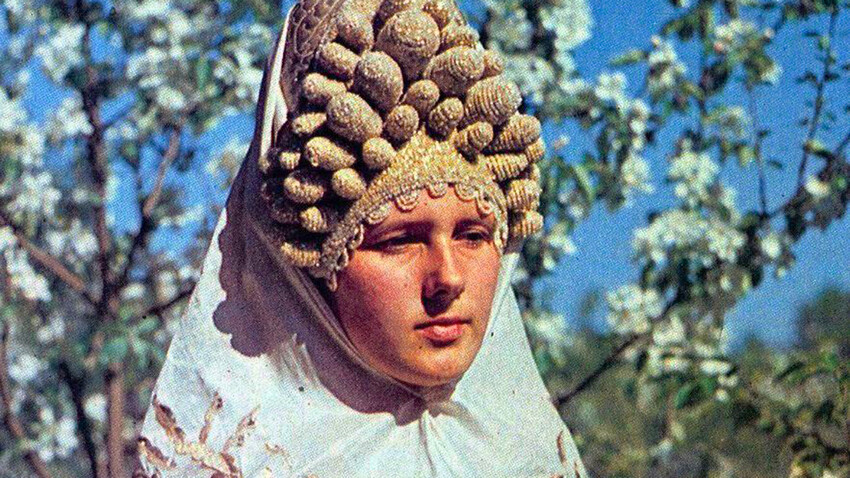

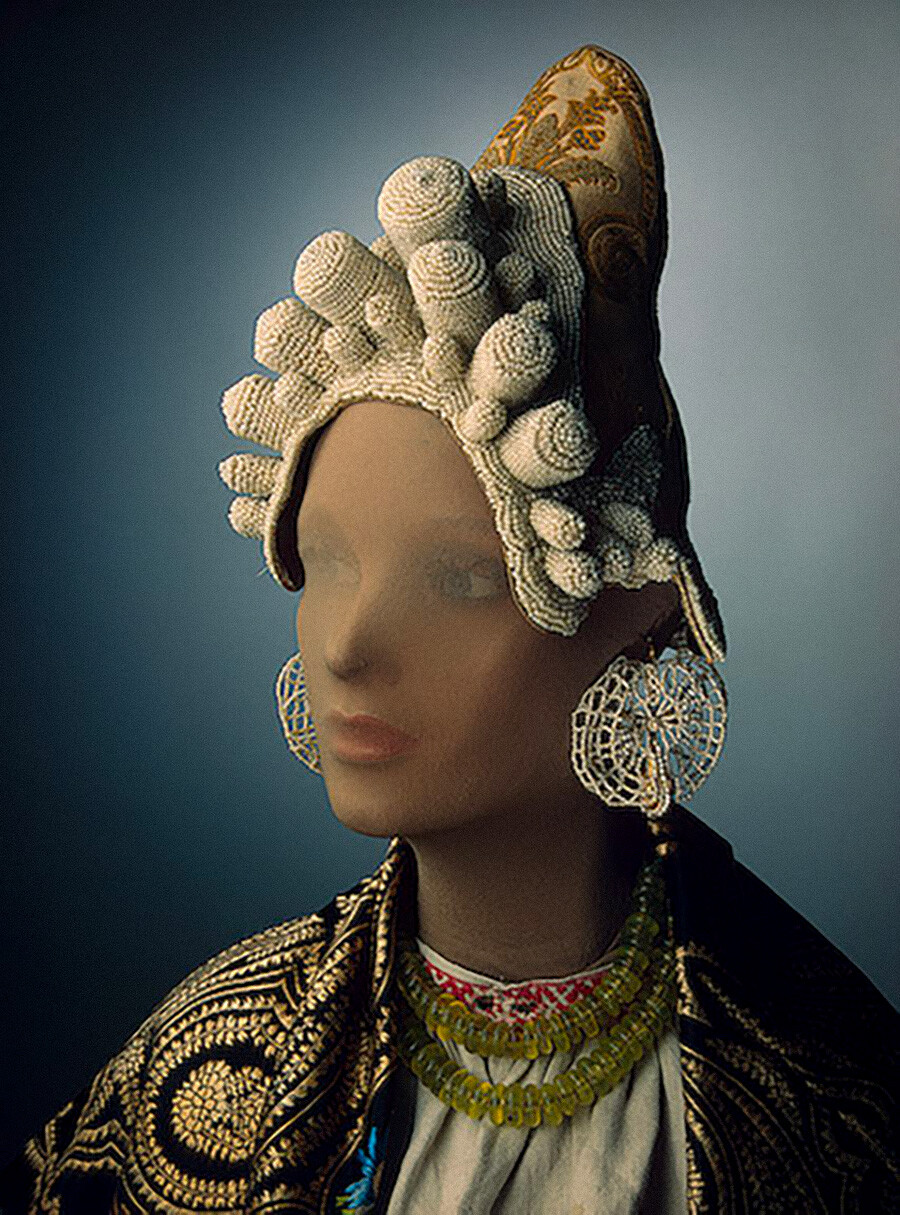

If the previous headdresses were worn predominantly in the south, this one was popular in the north of Russia. This classic kokoshnik from Pskov looked a bit different from its more everyday versions, due to its “knobs”.

It was believed that the more knobs there were, the better, for they symbolized fertility. There was even a saying: “As many children as there are knobs.”

A Pskov ‘shishak’ was a part of a bride’s wedding dress; often the ‘knobs’ were embroidered with natural pearls, while a headscarf embroidered with gold was worn on top of the ‘shishak’.

This variety of the kokoshnik, definitely one of the more unusual ones, was very popular in the Tver Governorate, so now its name is strongly associated with this region.

A ‘kabluchok’ in the shape of a cylinder was very much in fashion at the end of the 18th century – beginning of the 19th century, it was worn only on holidays – for this, they were manufactured from the most expensive materials, such as silk or velvet, and embroidered over with gems and gold. Usually, a pearl ‘podniz’ was also secured to it – a net covering the forehead of a woman wearing a ‘kabluchok’, because the main part of the holiday headdress covered only the top of her head.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox