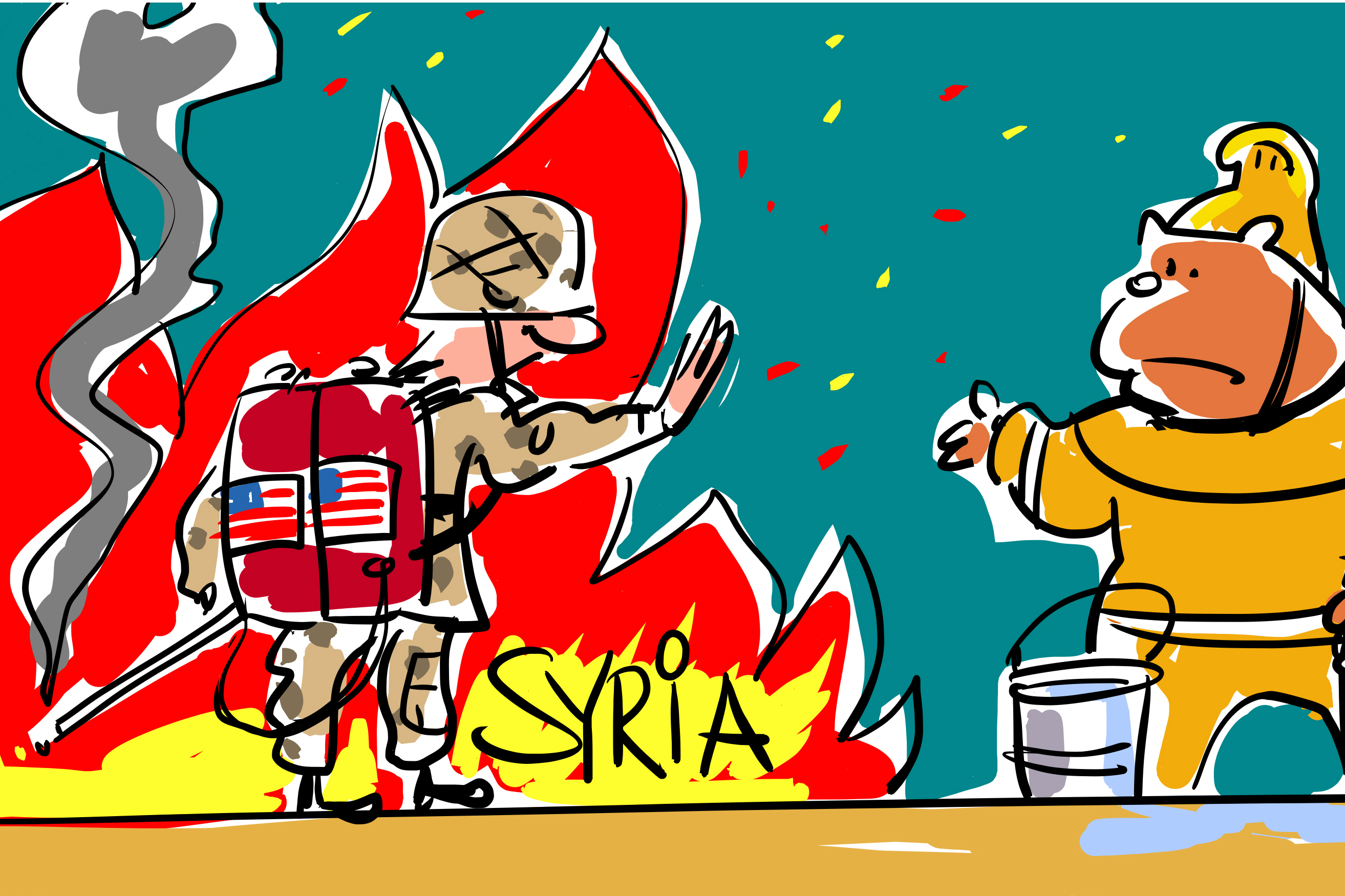

Who is really throwing gasoline on Russia-U.S. relations?

Speaking recently to the U.S. military at a conference in California, Pentagon chief Ashton Carter remained true to himself and emerged again not only as a harsh critic of Russian foreign policy, but also a fierce campaigner for "deterring" it.

He lashed out at Moscow for "playing spoiler" in the Syrian crisis, "throwing gasoline on an already dangerous fire," and supposedly being involved in "nuclear saber-rattling." Therefore, he proposed to work to "deter Russia's aggression" in Europe.

Carter's tough statements almost coincided with media reports about the FBI's willingness to assist their Russian colleagues in the investigation of the Russian passenger plane crash over Egypt’s Sinai Peninsula (which may be the result of a terrorist attack), which killed 224 people.

Such cooperation would be the first such interaction between the Russian and American security agencies since the crisis in Ukraine and Crimea’s accession to the Russian Federation.

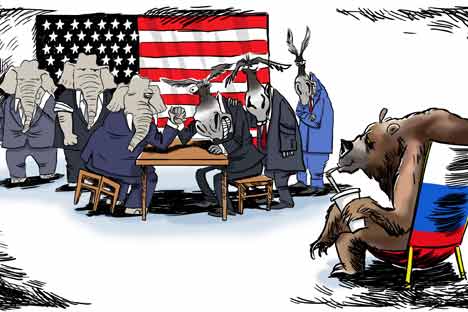

One administration, different voices

As for Syria, the statements by the head of the U.S. Defense Ministry stand in noticeable contrast with the line of the U.S. Department of State. Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov and his U.S. counterpart John Kerry have had a lot of talks in recent weeks on the subject of the Syrian settlement.

If accusations against Moscow about where it is throwing gasoline had come from the mouth of Kerry in Vienna, then it would have been, perhaps, the end of the whole multilateral meeting.

However, despite serious differences that persist in the position of Russia and the United States on the course of the Syrian settlement, it is still possible to talk today about a weak glimmer of hope for a compromise, rather than about the degradation of the situation.

In general, of course, such "stylistic differences" between the Pentagon and the State Department are par for the course. Apart from playing the "good and bad cop," this can be seen as the pursuit by each agency of its own departmental interests.

A desire to catch up

The Pentagon has long been looking for a reason and opportunity "to breathe fresh air" into the construction of NATO military structures in Europe. The Europeans have repeatedly been criticized by Washington for allocating to military spending a smaller share of the budget than what was stated in the plans and programs of NATO.

In addition, since 1985 the number of U.S. troops in Europe has fallen from more than 300,000 to just over 50,000. (This is less than in the Asia-Pacific region).

Now the Pentagon wants to "catch up" even despite the fact that the Ukrainian crisis, which served as a formal pretext for tightening rhetoric, is on the decline. Moreover, it has declined without NATO intervention, but by means of complex negotiations, in which, of course, Moscow’s Western interlocutors resorted to pressure, but of the economic, rather than the military kind.

Besides, many European leaders have begun to make increasingly frequent statements that without Moscow's participation it will not be possible to solve the Syrian crisis, not to mention the fact that it will not be possible to fully solve the Ukrainian crisis without taking into account its interests.

In such a situation, when the "ship sails," they have to hurry, of course, to stake out new plans for military construction in Europe. Preliminary decisions on these matters should be adopted at a meeting of NATO foreign ministers in December, and then approved at the summit of the alliance in Warsaw in the summer of next year.

Harsh statements by the U.S. military became more frequent after the beginning of Russia's military intervention in Syria, which has turned out to be fairly efficient, to the surprise of many in the West. Moscow's actions in the Middle East have been represented by some U.S. media and, most importantly, by the Republican majority in Congress, as a "failure" of the Obama administration.

Compensatory rhetoric

The Pentagon's tough rhetoric in this sense is intended to "compensate" for the propaganda damage, and not to give the Republicans the edge in the near future, when the presidential election race begins to unfold. Of course, U.S.-Russian relations today are going through the most acute crisis since the end of the Cold War. Perhaps one can already talk about a new Cold War.

The Obama administration, of course, would hardly want to leave unresolved crises in Ukraine and the Middle East as a legacy for his successor. And if the sides have managed to at least stop further escalation of the former, the second large-scale crisis remains not quite predictable by the degree of its possible spread to neighboring countries.

In both cases, the transition to at least "cold and rational" interaction with Moscow could bring substantial results. Instead, individual representatives of the U.S. administration are making statements that are difficult to describe as anything other than provocative. That's who is really throwing gasoline on the fire, and in so doing seriously fanning the flames of Russian-American enmity.

The author is a political scientist and a member of the Council for Foreign and Defense Policy, a Moscow-based independent think tank.

The opinion of the writer may not necessarily reflect the position of RBTH or its staff.

Read more: American Communists rest in peace behind Lenin's tomb>>>

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox