Discovering a home of eccentrics

Inside Olga Brendel's house. Source: kiaraz.org.

In the past, this hamlet was home to members of the Russian gentry and, later, the Soviet intelligentsia. These days, only eccentrics dwell here.

The place earned its name as the “Village of Eccentrics” some time ago, back when the founder of the community – nobleman Vladimir Brendel – was still alive. In 1927, Brendel, a biologist and a vet, was invited to stay by the leader of the republic, Nestor Lakoba. Abkhazia’s first vet built a big house on the seashore, and then other Russians started to settle next to him.

View Larger Map |

Brendel’s house operated on an open door policy that welcomed all manner of creative types: the owners hosted concerts and other events here; the man of the house played the piano and also spent his time painting and writing poetry. The house is currently occupied by his granddaughter, Olga Voitsekhovskaya-Brendel. She is working to keep the memory of her talented grandfather alive, along with the memory of her mother, a famous artist who was also named Olga.

The house’s walls are decorated with Abkhazia’s first mosaic; the interior is filled with paintings and large solid furniture. Olga (the younger) walks around the empty house in scruffy slippers and a blouse, listening to an old-fashioned radio – she says this is better than a TV. She has not been able to surpass her relatives in terms of artistic talent due to a disability (she was born with a withered arm), but she has carried the baton of what her grandfather started. Having studied the work of her own mother, she became an art historian.

Olga now works to protect the precious cultural past of this house and all its treasures and ornaments.

|

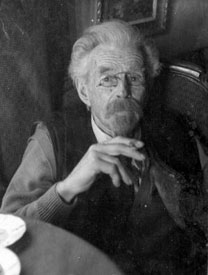

| Vladimir Brendel. Source: kiaraz.org |

“I’ve been robbed five times. The thieves took holy icons and the 1902 three-volume sets of Brockhaus and Euphronius. But they left the paintings alone – there are too many of them to carry away,” said Olga.

The paintings are arranged in a converted studio on the roof of the house. The creative house is nestled in on a strip of land between the railway and the sea. The ocean is only 30 meters (about 100 feet) from the garden fence. At first, the tracks were laid on the ocean side of the house, but they were quickly washed away by the waves. Now the rails are on the other side of the house. Luckily for the building’s sake, trains only pass very rarely, and the railway track is gradually being overgrown with brambles.

The other side of the house is the home of the composer Valery Chkadua – a man of 65 years, with a large hat and aquiline nose. He says that, as a music student in Moscow, sculptors were queuing up to mold his profile.

Valery studied under Shostakovich and Prokofiev. He wrote three ballets: “Ritsa” (the first in Abkhazia’s history), “Narta,” “The Call of the Revolution,” plus another 40 or so compositions.

In 1994, after the war for independence and at the personal request of President Ardzinba, he wrote Abkhazia’s national anthem, which included various folk motives. He had to write it in winter and the house was not heated at the time, which meant temperatures were below freezing inside the house. Valery refused to receive royalties for his work, so the president decided to give the composer “creative” housing as a thank you.

In part of the house the walls are plain, painted in blue paint. A mountain bike is propped up in the hall, and a Petrof piano stands proudly in a corner of the sitting room. Piles of music, a bust of Tchaikovsky, an icon of St. Pantaleon and a picture of the singing hare and wolf from the Russian cartoon “Nu, pogodi!” are all overhead.

The composer plays energetic chords, but the Petrof piano squeaks and clangs, painfully out of tune.

Related:

The gallery: Abkhazia - a stirring child of Caucasus

Nature calls the tune in a land of harmony, history and adventure

“During the war I took the keyboard to pieces so marauders wouldn’t steal it. But I was never able to put it back together properly,” Valery says calmly. Luckily, he has no need to listen to the melody, since the sound forms right in his head.

A huge rock lies next to the piano.

“This is a ritual stone from the Bzybsky gorge. I dragged it home so it could give me musical inspiration. I am also a bit of a psychic,” says Valery. He is also a writer and a linguist and has published seven books on the origins of the worlds’ languages – expert pieces that would be hard for a layman to understand.

The incredibly complex Abkhazian language (which is derived from Hittite) is a very interesting subject for linguistic research. The father of 70-year-old Margarita Orelkina spent many years studying this subject, and Margarita now lives next door to the Brendel’s house.

The historian, artist and linguist Valery Orelkin settled in Abkhazia in 1947. He made a garden on the seashore and started to grow plants. To this day, the fruits of his labor remain in the form of a jungle of greenery surrounding a small house. There are plants with more than a thousand names: Pitsunda pine, pecan trees, ginkgo, oleander, grapefruit and mandarins…

The place earned its name as the “Village of Eccentrics” some time ago, back when the founder of the community – nobleman Vladimir Brendel – was still alive. Source: Lori / Legion media.

His idyllic life did not last for long. In 1949, Orelkin was arrested for political agitation. He spent five years in labor camps before returning and painting a picture called “The Eclipse of the Sun.” The piece depicts rows of hunched prisoners and a cloud in front of the sun in the form of Stalin’s sideways profile.

Margarita grew up as a dissident. She helped her father paint the figures of the prisoners, posing with her hands behind her back. She graduated from Moscow State University as a journalist, but was subsequently thrown out of the Writer’s Union for reading Solzhenitsyn.

Now, having suffered a heart attack, she tends to keep to herself. Every fortnight she goes to town to do her shopping. She has three dogs and 14 cats. Her neighbors think she is a little strange, but they still do not hesitate to send any homeless animals her way.

Inside Olga Brendel's house. Source: kiaraz.org

Since spring, Margarita has taken yet another lost soul under her wing – the 62-year-old pensioner Alexander Polezhaev. In the past, he was something of a vagabond with a taste for adventure; he is a former thrill-seeker who has now come to seek out a quiet life in the fresh sea air. He spends his time catching fish and finding mushrooms for the table, and he also helps out around the house.

Another neighbor in the Village of Eccentrics came to these shores about a year ago. Formerly a teacher in Krasnodar, Alexander Tyutchev (now 64) also came to Abkhazia in search of peace and solitude. Right on the seashore by the Kelasur River he sculpts strange figures: birds, deer and lizards. Hundreds of stones and pieces of driftwood that wash up on the shore are transformed into these strange and beautiful objects.

“Before there was a rubbish dump here,” Tyutchev says. “And now everyone keeps it neat and tidy. Women come here with their children, ask if they can sit here for a while, let the children play.”

Over the past year, Tyutchev has become a part of the local landscape and has certainly carried on the baton of the eccentric Kelasur community.

Is there a future for quirky, earthy places like this – a strange oasis in a world full of smartphones, black Lexus cars and Adidas tracksuits imported from Chinese sweatshops? These eccentrics are stronger than you think: they will stand their ground, come rain or high water. And they will continue to communicate with their muses – wherever these may be – blissfully free from worries about keeping up the Joneses.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox