Vladimir Makanin: On writing as chess play

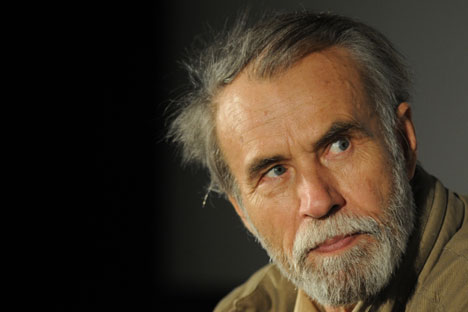

Vladimir Makanin

TASSWe found Makanin at his quiet family home, his second residence, outside Rostov-on-Don. The country house is complete with newly created garden, swings and a cozy veranda, the perfect spot to discuss literature.

Rossiyskaya Gazeta: You are a mathematician. Does the ability to think methodically help a writer?

VM: Mathematics is beautiful, perfection even, although for me it is also a little cold. I was a diligent and distinguished pupil, but the subject still didn’t touch my heart. My personality was not formed by

Vladimir Makanin was born in 1937 in the Urals town of Orsk. He graduated from the faculty of mechanics and mathematics at Moscow State University and went on to work as a lecturer in higher education. His first novel “Straight line” was published in 1965.

In 1999 he was awarded Russia’s State

Close to the moment I had beaten my opponents, they’d start to sweat, wriggle in their chairs and smoke (which was allowed at competitions in those days). Meanwhile, the boy who sat quietly opposite them-me-enjoyed the game and that unique sense of meeting a challenge, which has served me so well in life. Mostly I mean here the demands of writing a text, and its casual, almost playful striving to defeat me.

No longer a boy, now I am the one sweating,

RG: Your first works raced out like new comets, yet you seem to write with such ease. Does this apparent ease belie the process of writing?

VM: Again back to chess: “The victor is he who wins while playing blacks.” To win with whites is to write like other people do, and rack up fast points. But to write a novella or novel on uncharted territory with new types of characters is a game played with blacks.

RG: Do you write your stories from beginning to end?

VM: No,I write in sections. I write key scenes randomly and sometimes I start from the end. It’s a bit like being in the kitchen. In order to

RG: Did you read a lot in your youth?

VM: There were not as many books around when I was young. I was lucky

Reading was not a stream but rather a river for me. Remarque’s “Three Comrades” was a massive hit at

RG: Your novels generate a lot of

VM: There are two processes: creation and consumption. An author is only responsible for the first. He can write a novel, a drama, but has no say in how it will be received. It is beyond his influence. Society consumes what you produce and it can regale you tomorrow and trample you a month later. Or give you recognition only after your death, or never. But again, that is not down to you, your job is to create.

RG: The foreword to the Spanish edition of “Asan” features the phrase: “Makanin has succeeded in looking into the world beyond the level of morality.” What do you make of this?

VM: While not dismissing morality, I would also never presume to deem who is better or worse than the next person. It’s just life. They say that I managed to see the phenomenon of war with different eyes in “Asan.” I did not set out to do this. You could argue that I could not have written it differently anyway. It is not about trench warfare but rather

RG: There is now a sense of a completely new era

VM: A new era has indeed arrived, and it is not easy to grasp, whether you write one short story and then two or three more right behind it. I am not so well versed in politics. But I do not regard the future as being apocalyptic.

RG: What is the saving grace, beauty?

VM: Beauty tries to save, all the time. And beauty beckons constantly. A person goes about his life and then suddenly something makes them stop and notice that they are living a swine’s existence. And that is when this pervasive beauty shakes your soul to the core with its lessons. And what of it, do you finally understand everything? Unfortunately, no. Within a month you’ll be living just as always and will have forgotten this, everything is back as it was and you have to start all over again. But some glimmers still got

First published in Russian in Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox