Russian hipsters get a grip on hip

Russian hipsters are a segment of Russia's first post-Soviet generation: They have grown up with capitalism, and have not inherited the esoteric regimes of brand differentiation so dear to their Western counterparts. Source: RIA Novosti

Where the bohemians used to have dreadlocks and go to artsy cafes, and the establishment wore grey and went to church, it seemed as though everyone saw himself or herself as belonging to the counterculture at the start of the 21st century. Bankers and software developers were just as likely to have tattoos and quote Jack Kerouac as anyone else. Ideology, if it still existed at all, no longer wore uniforms.

The change that Brooks identified took place at the same time as the re-emergence of the so-called hipster. Although the word “hip” emerged early in the 20th century, the suffix was only added in the 1940s. In the ’40s, the term “hipster” applied to mostly white, middle-class kids who attached themselves to the jazz scene.

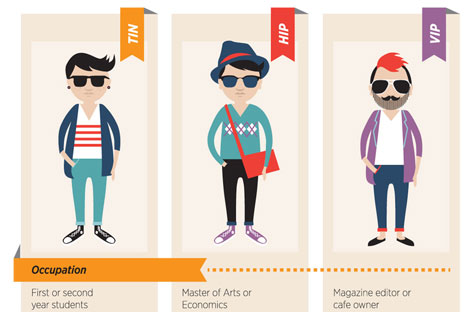

Who are Russian hipsters?

Click to view the infographics. Drawing by Natalia Mikhaylenko

The 1950s saw a transition in the hipster—or at least the meaning of that word—when it became associated with a sort of drug-fuelled nomadism, typified by writers such as Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsburg.

And then, suddenly—nothing. The hipster was put into something like cryogenic storage, only to re-emerge in the 1990s, where it assumed an aesthetic form somewhat akin to a mix-tape. The hipster, in its most recent incarnation, parades a metonymic mish-mash of influence. He or she is the person who exerts enormous effort to combine almost every counter-cultural movement of the 20th century into a single style…sometimes into a single outfit.

The hipster represents time-space compression at its most radical. He or she has stolen Sylvia Plath’s cardigan, is crowned with a Beatles mop-top and parades a ’70s cop-show moustache beneath Dylan’s Wayfarers.

Alternatively, the hipster appears in your grandma’s jumper and a Palestinian keffiyeh. He or she will be taking a “selfie” on their iPhone, smoking Gitanes and stuffing a biography of Che into a kitsch, gender-neutral Sesame Street handbag. She will be listening to early Grizzly Bear and he will be looking like early Grizzly Adams.

The hipster appears, in other words, to be somewhere between a person who has watched every television show in the past 50 years and someone who has never seen a TV set. It was bound to catch on—and it did.

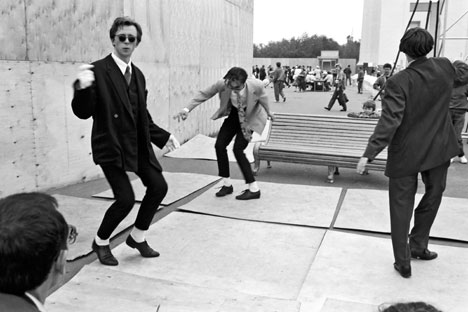

In Russia, the term “stilyagi” was used in the Soviet era, particularly in the ’50s, to describe—often in derogatory terms—a youth subculture obsessed with fashion and music (particularly jazz). Half a century later, the Russian hipster was born. Or was s/he? Is the Russian hipster a copy or only a cousin of the creature we find in the West? Or is he or she no relation, except by name? In the late 1980s, some economists and social theorists became enamored with the term “glocalization”—an ugly portmanteau of “globalization” and “localization.” What it referred to was the way in which regional cultures domesticate and change global trends.

In Russia, the term “stilyagi” was used in the Soviet era, particularly in the ’50s, to describe a youth subculture obsessed with fashion and jazz. Source: RIA Novosti

As awkward as the term is, it is probably the right one to use here. Russian hipsters are undoubtedly half-turned toward the West, although it would be a mistake to see them simply as extensions or dupes of some Western cultural “empire.”

Not yet embarrassed by the gaudiness of big brands, the Russian hipster is far more likely to visit Starbucks than his or her Western counterpart. It is not that the Western hipster rejects consumption itself. Indeed, as part of Generation Beard, the only consumption the Western hipster male consistently rejects is the razor blade.

It is, rather, that he or she is more sensitive about the relationship of branding to culture—especially mass culture. For the Western hipster, Starbucks is to be refused because it is the sine qua non of both “corporate capitalism” and plebeianism: the gauche, neon-lit strip mall of coffee. Russian hipsters are a segment of Russia's first post-Soviet generation: They have grown up with capitalism, and have not inherited the esoteric regimes of brand differentiation so dear to their Western counterparts.

Yuri Saprykin, former editorial director at Russia’s uber-cool Afisha entertainment magazine and website, says that he first came across the word “hipster” in the Russian media in 2003. At first, it pointed to a fashion style that differed little from what might be seen anywhere else in the world. Within a couple of years, however, it also became a derogatory term.

This was the case not just for elements of the press, but for hipsters themselves, some of whom had become visible through participation in public demonstrations and actions in support of opposition figures. Segments of the Russian media argued that this was not, in fact, political commitment at work, but the decadent actions of impulsive fashionistas engaging in political rallies for no other reason than the idea that it was cool.

More seriously for some, hipsters were the incarnation of that dreaded figure, the “demshiza”: people who, on their way to liberal democracy, had somehow lost their minds.

But if “hipster” had come to be a term of ridicule in the minds of some Russian journalists, it had become even less acceptable in the minds of hipsters themselves.

And here, Russia and the west find common ground.

The name "hipster" is now invariably applied to someone else, usually as a pejorative. In a recent New Yorker blog, Teju Cole defined "hipster" as a person "who has an irrational hatred of hipsters." The use of the word has come to indicate someone else - those people over there who think they are cool, rather than actually being cool…um…like me.

There are few things more hipster than being anti-hipster. Of course, this is a paradox – but the hipster is nothing if not paradoxical: he or she is that creature who exerts enormous energy on looking like they haven’t expended any energy on how they look.

They possess a meticulously constructed appearance designed precisely to communicate that they don’t really care about appearances. They walk in a way that makes an impossible demand on onlookers: Hey – look at me! Why are you looking at me? I don’t care what you think.

Many suggest that hipsters are on an even lower rung than those who aestheticise politics; they commit the far worse crime of politicising aesthetics. The hipster, so the logic goes, is the person who thinks wearing a Ché Guevara shirt is a radical political act. The hipster cannibalises the accessories of protest movements while simultaneously de-fanging them – or so the argument goes.

There is an element of truth to such charges. Politically, they are unaligned, even rudderless. Critics see no coherent political voice or vision in hipsterdom. Perhaps indeed the category "hipster" is more valid for marketing than political purposes.

In any case, hipsters are undeniably "post-ideological." That they are not easily aligned with old-style political blocs may show as much about the inadequacy of this aged system as the political commitments of hipsters themselves.

People commonly respond to cultural change with either visions of utopia or apocalypse, usually neither of which – in the long run – turn out to be warranted.

It may be disappointing, but it’s likely that hipsters in Russia represent neither the first rumblings of post-Soviet civil society, nor the unmistakable sign of the decline of civilisation.

Indeed, perhaps, 50 years from now, what the emergence of hipsters will be seen to represent might be little more than just how far young people will go with their facial hair and sunglasses if left unchecked.

Chris Fleming is a senior lecturer in the humanities and communication arts at the University of Western Sydney.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox