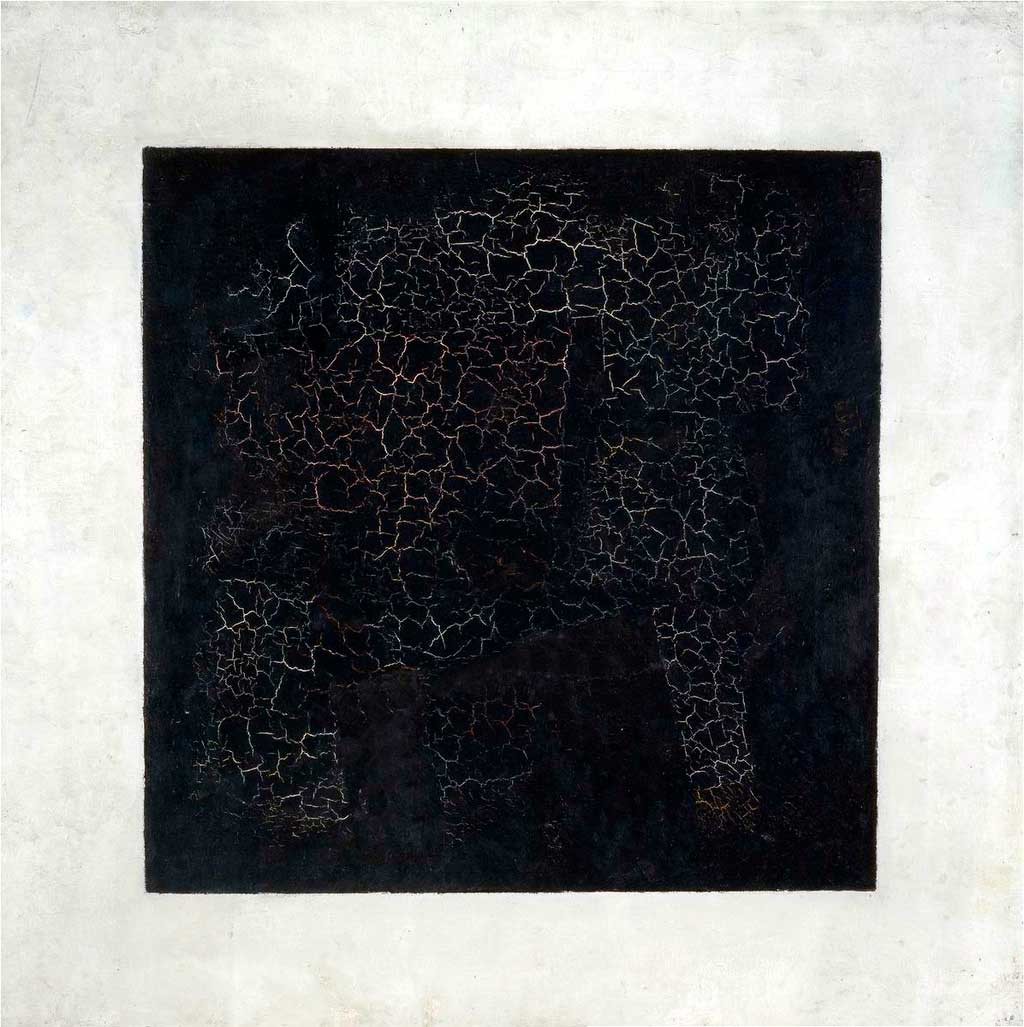

Malevich himself used to say that he had created “The Black Square” in a mystical trance, under the influence of a "cosmic consciousness" experience. Source: Yuri Somov / RIA Novosti

Kazimir Malevich painted “The Black Suprematist Square” in 1915, in the heat of World War I, but he first conceived the idea 2 years ago in 1913. Initially, “The Black Square” was not intended to have any symbolic meaning: its purpose was to solve artistic problems.

|

| Kazimir Malevich (1879, Kiev - 1935 Leningrad, now St Petersburg). Source: RIA Novosti |

However, as is often the case with masterpieces, the painting spurred a multitude of interpretatio

To begin with, “The Black Square”is not a square. None of its sides are parallel to the frame. Besides, it is made of mixed colors, none of which is black. If you look closer, you will see that the paint has cracked over time, creating an intricate network of

One urban myth has it that “The Black Square” came to be by accident: a major futuristic exhibition was fast approaching at which Malevich and his fellow artists had a huge hall reserved for their works.

On learning that there would be a lot of wall space to fill up, the artists urgently began creating more works. Malevich couldn't get

Malevich himself used to say that he had created “The Black Square” in a mystical trance, under the influence of a "cosmic consciousness" experience.

He even accentuated this by making sure that at the exhibition, the picture was hanging to the right of the entrance, the place reserved to Christian icons in accordance with the Russian tradition.

Alexander Benois, an art critic and himself an artist, immediately noticed this. "That is undoubtedly the icon that Messrs Futurists oppose

The other squares

Apart from “The Black Square,” Malevich created a red square and a white square. In fact, there exist more than one “The Black Square.”

Kazimir Malevich painted “The Black Suprematist Square” in 1915

WikipediaThe second painting was done in 1923 for the Venetian

Malevich painted his third “The Black Square” for the 1929 exhibition in the Tretyakov Gallery.

The story goes that he was asked to do so by the gallery director, who hated to have to exhibit the by-then crack-painted original. The second and third “Black Squares” have no signs of cracks, probably because the artist used an anti-cracking varnish on them.

A fourth “Black Square” was rediscovered in 1993: a person whose name is unknown used it as collateral to get a bank loan in Samara. The bank came into possession of the

The government banned an open auction lest the masterpiece should leave the country; this “Black Square” was sold for $1 million to Russian tycoon Vladimir Potanin, who then handed it over to the State Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg.

Not only Malevich

Suprematism was founded by Kazimir Malevich in the 1910s as a movement in abstract art. Its followers combined multicolored basic geometric shapes (the circle, the square, the triangle, and the line) in asymmetric compositions. Suprematism was widely used in the art of the poster, and also in architecture, design, and scenography.

Malevich was not the first artist to experiment with squares and the color black. In 1617, English doctor,

Paul Gustave Dore used a black square to illustrate the dark age of the Russian history. There is also “Negroes Fighting in a Tunnel at Night” by Paul Bilhaud, which is also quite similar to Malevich's “Black Square.” Finally, in 1893, French journalist and writer Alphonse Allais came up with a black horizontal rectangle entitled “Negroes Fighting in a Cave.”

Monument on canvas

Like many great masterpieces, the story of “The Black Square” continued after the author's death.

In accordance with Malevich's will, a "suprematist rite" was performed at his funeral in which “The Black Square” once again played an iconic role: the square was painted on the artist's coffin, and a reproduction of the painting was mounted on the hearse truck.

The exact location of Malevich's grave was forgotten during World War II. In 1988, enthusiasts installed a commemorative sign in the area where the artist was believed to have been

Malevich's grave got rediscovered in the late 2000s, but it turned out that the plot had been used for a housing project. Thus “The Black Square” remains the

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox