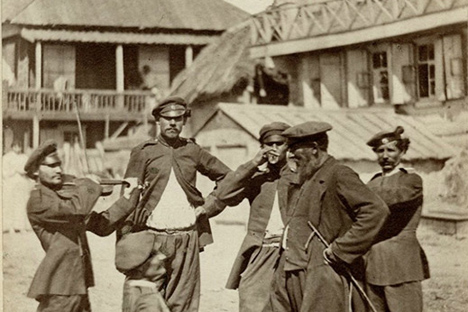

History of Don Cossacks started in the 15th century and continues to our days.Source: free sources

One hot summer’s day in 1914, the alarm was raised in all Cossack villages across Russia. Cossacks with a small red flag in their hands, a signal to mobilization, were dispatched on the fastest horses to reach every remote part of nearby areas. Seeing them, people dropped whatever work they were doing in the fields and hurried home, to prepare to march off to battle in the First World War, which would change Russia's destiny forever.

"We don't want to protect landowners"

Cossacks, a class of Eastern Slavic people that by the start of the 20th century numbered about 4 million, emerged in the 14th-15th centuries, forming democratic communities in the great river basins of what is now southern Russia and Ukraine.

Since their early days they had maintained the traditions of military training in their families, were excellent horse riders and brave and skilful soldiers. By 1914, their loyalty to the authorities had been boosted by a preferential tax regime (they paid practically no taxes or levies), free education and health care. Yet the majority of ordinary Cossacks were rather poor. Their only source of income was land, which they either worked themselves or leased. However, land was often unfairly distributed by Cossack chieftains.

Cossack divisions, whose supreme commanders were calledatamans, were one of the main pillars of Russia’s ruling regime. They were frequently used to disperse rallies and to suppress peasants and workers during the 1905 revolution. Yet some of the Cossacks refused to go against the people and protect landowners. Frustrated by their never-ending hardship, in some villages Cossacks even dared to rise against the authorities. But the outbreak of World War I changed everything.

Wasted heroism

The name of CossackKuzma Kryuchkovwas to become known across the whole of Europe during the war. Kryuchkov, together with three fellow soldiers, killed a German cavalry platoon of 27 men, and became the first soldier in World War I to be awarded the Cross of St George, for "undaunted courage". Overall, more than 120,000 Cossacks received different distinctions of St. George in the course of the war.

In the meantime, villages left without a male workforce were slipping deeper into poverty.The authorities had completely lost the support of the Cossacks by the time the February 1917 revolution took place. A number of Cossack units that were sent to disperse the protesters not only refused to obey the command but joined in the uprising. In October 1917, the Bolsheviks overthrew the provisional government of Alexander Kerensky, and many Cossack units in St Petersburg went over to their side.

The revolution divided the Cossack people. Many poor Cossacks welcomed the first decrees of the new authorities: The Bolsheviks announced that Russia was quitting the war, promising land to the Cossacks andnot to interfere in their affairs so long as they did not oppose Soviet rule. And yet it was in the very heart of Cossack Russia that the main hotbed of resistance to the new Soviet authorities was to emerge, on the banks of the river Don.

In 1918, General Pyotr Krasnov, who came from a generations-old Cossack family, became the Ataman, or commander, of the Don Cossack Host, a formidable independent Cossack army fighting on the side of “White Russia” against the Bolshevik authorities. Krasnov cancelled Bolshevik decrees and declared the lands of the host an independent state with himself a dictator. From 25,000 to 40,000 "red" Cossacks were executed and another 30,000 exiled.

Krasnov sent a telegram to Kaiser Wilhelm II, the German emperor, with an offer of cooperation in exchange for recognition of his "state". Berlin sent Krasnov trainloads of weapons, but after Germany retreated, Krasnov's "tsardom" broke up and he was forced to flee to Germany. By 1920, Cossack resistance was over.

The Bolsheviks began to exterminate Cossacks, seeing them as a class hostile to the Soviet authorities. Many were executed, while whole families were banished from their land and exiled to other territories in order to "dilute" the Cossacks' social unity. In 1922, the lands belonging to Cossack hosts were absorbed into the Soviet republics of Russia and Ukraine. However, this was far from the end of the Cossacks.

Enemy within

In the late 1930s, the USSR began to prepare for the war that it anticipated was to come. Restrictions on Cossacks' rights to serve in the Red Army were lifted, and they were allowed to wear Cossack uniform. When World War II started, many impoverished Cossacks rode into battle on scrawny collective farm horses armed with just swords and knives. However, that in no way diminished their courage: They would jump from the saddle onto tank armor, cover observation slits with their coats and set tanks on fire with petrol bombs. Some cavalry divisions were renamed Cossack divisions before World War II, even though Cossacks formed just a small part of them: The enemy was terrified of the very word "Cossack".

However, the truth is that Cossacks fought not only on the side of the USSR. German propaganda tempted them with the idea of revenge for their losses in the Civil War and with the promise of setting up an independent Cossack state under the name of Cossackia. Émigré Cossacks and the Cossack population of the occupied territories joined German forces. Furthermore, General Krasnov agreed to ally himself with the Nazis and serve at the head of Cossack units made up of White Russian émigrés and Cossack prisoners of war.

Cossacks served as guards on occupied territories, fought with the Red Army, with Yugoslav and Italian resistance fighters. Sadly, the war years broke not only the spirit but also the honor of many Cossacks. Under the command of German General Helmuth von Pannwitz, Cossacks took part in war crimes against the populations of Eastern Europe, including mass murder and plunder.

In May 1945, Germany capitulated. The Cossack Corps was ordered to cross the Alps into Austria to surrender to the British. Churchill, Stalin and Roosevelt agreed that former Soviet citizens who had fought on the enemy side and had been captured by the Allies should be handed over to Soviet forces.

Having crossed the Alps under Krasnov's command, the Cossacks surrendered their arms and were placed in prisoner-of-war camps near the town of Lienz. The "handover" began on May 28. During a church service, British troops attacked Cossacks and, brutally beating them, started pushing them into trucks, which then transported the prisoners to the territory under Soviet control. The operation lasted two weeks. According to different accounts, from 40,000 to 60,000 people were thus handed over. These included first-wave émigrés who just happened to be near Lienz at the time, who were not Cossacks at all and had never been Soviet citizens. Over 1,000 people were killed for attempting to resist capture.

The leaders of the Cossack divisions which had fought on Germany's side – Krasnov, Lieutenant General Andrei Shkuro, German general Helmuth von Pannwitz and others – were hanged in Moscow in 1947. The other prisoners, including women, were sent to Soviet labor camps. In 1955, those of them who survived were amnestied. They continued to live and work in the USSR, keeping their past a secret.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox