Russian wine: Measuring up to the competition

Wine critics have praised the best of Russia’s new wine output. Source: Shutterstock / Vostock Photo

Wine-producing countries such as Chile, Argentina and South Africa have traditionally been labelled "New World", a phase that denoted new and exciting as opposed to established and traditional, ie, France. But today the term appears hopelessly outdated when applied to countries such as Chile and Australia, which have been producing high quality wine for many decades.

'New World'

The true New World of wine is now made up of countries such as Russia, India and China; newcomers to premium-wine production who are slowly starting to export and whose wine is appearing in our supermarkets and restaurants. As of 2014, British consumers can purchase Russian sparkling wine from Tesco and Indian reds from Waitrose.

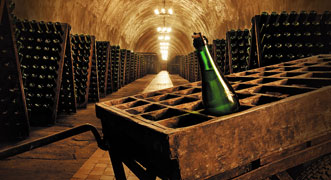

This "new" New World of wine has seemingly appeared out of nowhere. The people behind it are often investors who had travelled and worked abroad and decided there was a niche for competitively priced, premium domestic wine, in countries with no track record for quality. Pavel Titov, CEO of the Russian sparkling wine house Abrau-Durso studied and worked in the UK, as an investment analyst for City firm Merrill Lynch. His father, Boris Titov, invested more than $20 million in returning quality sparkling wine production to Abrau's cellars; its success in revitalising the brand encouraged others to invest in Russia’s premium wine industry.

In Asia, Rajeev Samant, the former Silicon Valley entrepreneur, founded Sula Wines in Nashik, India in 1999 to capitalise on the westernisation of lifestyles in urban centres such as Mumbai. Similarly, Silver Heights, China’s premier boutique winery was founded by Emma Gao, a Chinese national who had spent time in Bordeaux. Like their counterparts in Chile and New Zealand, the wine newbies began by planting crowd-pleasing, internationally recognised varieties; the ubiquitous sauvignon blancs and cabernet sauvignons. The initial focus was on the domestic market.

But Russia has taken a different path in recent years, illustrated by its two most important wine regions, Krasnodar and Rostov. The investment in these regions is almost exclusively Russian: it means Russia remains in control and is not reliant on potentially fickle foreign investment for growth.

In contrast, the French luxury goods firm LVMH – which own several champagne brands – has been permitted to invest massive sums in the wine-growing areas of China and India. It wanted to produce a homegrown sparkling wine with the brand power of Chandon Champagne; a gamble, considering sparkling wine sales in Asia are low for its population.

Sparkling wine tradition

But Russia has a large population with a long history of drinking sparkling wine, so why have international conglomerates not invested in its vineyards? Darrel Joseph, a Decanter magazine judge and Russian wine expert, suggests firms may be discouraged by red tape. "The industry’s biggest weakness is undoubtedly the rather inane bureaucracy and laws that make it so difficult for small wineries to survive, let alone be established," he says.

However, a legal framework has the potential to push Russia ahead of its competition. There are few regulations or quality-control measures governing the infant (quality-led) industries of China and India. Russia’s wine producers, led by Abrau-Durso’s Boris Titov, agreed to ban the term Sovetskoye Shampanskoye (a generic brand of sparkling wine produced in the Soviet Union) from labels, and have discussed creating a formal appellation system for the two main production areas: the Rostov-on-Don river valley and the Northern Caucasus. This will ensure winemakers are committed to minimum quality standards and production values. The proposals are likely to go ahead.

Cultural factors are important. Alcohol consumption is illegal in several Indian states, overall consumption is very low (around 0.1 litres per head) and little is exported. China has no aversion to alcohol, but the national drinks have long been beer and the spirit baijiu, now produced in China by LVMH. Only 8 per cent of the population drinks wine. So Russia’s wine makers have a head start: the country has a history of wine consumption. Moreover, demand is rising across urban Russia – in 2012, almost 65 million nine-litre cases of still wine were sold in the country.

But Russia’s trump card is its natural resources, which critics say are richer than those of China and India. The wine consultant Michel Rolland recently told a trade publication: "My current knowledge does not allow me to think that India or China are able to produce fine wines equal to Napa (California) or Mendoza (Argentina)."

Of course, Russia too has its challenges; most of Russia is too cold to ripen grapes and in Rostov the vines have to be banked up in winter to keep them alive. But Krasnodar usually enjoys hot, sunny summers and in good years can easily ripen grape varieties such as chardonnay, pinot noir and riesling.

Darrel Joseph also underlines the point that Russia has not been solely reliant on global names such as sauvignon blanc and merlot, and that much of its potential is yet to be exploited. "Its indigenous grapes are very important," he says. "There aren’t so many, but the ones that make delicious wines, such as krasnostop zolotovsy, make for unique selling points."

A new global wine maker?

Wine critics such as Jancis Robinson, Jamie Goode and of course Darrel Joseph have praised the best of Russia’s new wine output. The latter says: "The quality of most wine styles – sparkling, dry and even sweet – is constantly on the rise."

China’s wines have been praised but India’s wines have not received any significant plaudits from critics, apart from those from the Sula winery.

Russia deserves recognition for its championing of native varieties, rapid progress and growing international recognition, all built on almost exclusively domestic investment.

But will Russian ouput ever reach the global status of, say, Chilean wine? "It will take at least another decade or more, but with proper investment, it could be a global wine player," says Joseph. The biggest potential stumbling block for wider global sales was the current political climate, which would clearly have a marked effect on consumers’ perception of the wine.

Fancy a taste of imperial Russia? Enter this competition and 12 bottles of delicious Abrau-Durso, the last word in Russian ‘champagne’, could be yours.

Partner generated content

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox