Happy Soviet New Year’s Eve

New Year table, Soviet diet style. Source: Anna Kharzeeva

New Year table, Soviet diet style. Source: Anna KharzeevaNew Year’s Eve is a huge deal in Russia. It was made into the main holiday of the year during the Soviet era, since it wasn’t possible to celebrate a religious holiday like Christmas in an atheist state. As a result, New Year’s Eve is both a time for spending time family and having a party with friends.

Most young Russians spend New Year’s Eve like this: From 9pm-midnight, you stuff yourself with the tastiest dishes your mother and grandmother can make. Then, as soon as you watch the broadcast of the president making his speech at 11:55, and hear the bells in the Kremlin tower strike 12, you’ll be out the door with three bottles of champagne up your sleeve. After a very civilized night out, you come home and collapse into bed at 5am, but can’t sleep until 9 since the fireworks go on until sun-up.

For the next three days, you will finish off everything that wasn’t eaten on Dec. 31. Good thing Russians are officially off work until Jan. 11!

New Year’s Eve dinner always includes Olivier salad; white bread with tiny canned fish known as shproty; an abundance of mandarins or oranges; the beet salad called vinaigrette; herring “under a fur coat” of carrots, potatoes, beetroot and onions; pickles; and a bottle or two of Soviet champagne. For dessert, in my family there would be “biskvit” – the only type of cake ever to be made in my family. Ever.

The best effort was always made for the most special night of the year, although what that effort could result in depended on the era and financial ability.

“My mother said that growing up I ate one orange. She went to the Torgsin [a special store that accepted payment only in hard currency, not rubles] and exchanged a silver spoon for one orange,” my grandmother said, remembering New Year’s Eves of her childhood

I ask if that was a damn good orange – one worth family silver – but she can’t remember. I pretend I’m not upset and think of ordering a silver orange to use up my rubles before their value decreases further.

As for vinaigrette, granny remembers that when they lived “in evacuation” during World War II, her mother would make vinaigrette, and the people in the village they were evacuated to told her that they “had all the ingredients available, but they only serve this sort of food to pigs.” I must have overheard that story at a very young age, as I never ate vinaigrette either.

The same villagers seemed keen to learn to make biskvit. During those years, presents for soldiers at the front were collected in every town, and my great-grandmother made biskvit for the collection. Apparently everyone was very interested in the cake. At least according to the legend. I’ve noticed over time that most stories involving my great grandmother feature everyone being stunned and amazed by the things she does!

This New Year’s Eve I’ll miss out on both the 9pm dinner and the midnight party, as I’ll be in the sky en route to Beijing and then Sydney. I will do my best to amaze the people in the “village” with my vinaigrette and biskvit as soon as I hit the ground, though. Hopefully that won’t require selling family silver either.

Biskvit

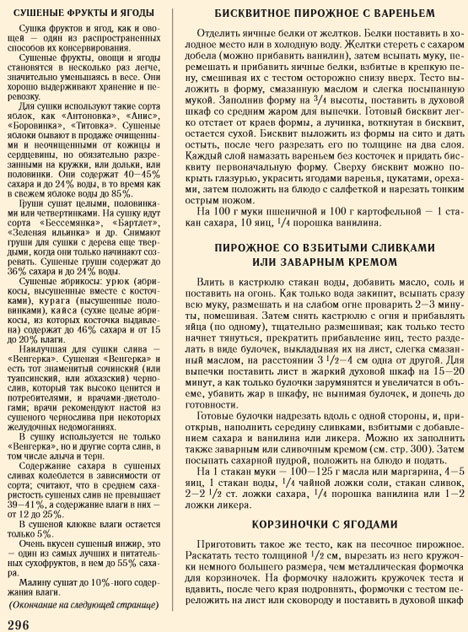

The recipe from the Soviet Cook Book, page 296. Click to enlarge the image

Separate the egg whites from the yolks. Put the whites in a cool place. Beat the egg yolks with the sugar until you can no longer see any white. You can add vanilla here. Then add the flour. Stir. Whip the egg whites into a solid foam. Mix them into the dough gently.

Ingredients:

100 grams wheat flour; 100 grams potato flour;

1 cup sugar; 10 eggs; ¼ tsp vanilla

Pour the dough into a springform pan that has been lightly greased and floured. Fill the form ¾ full. Put in the oven at the average temperature for baking. Bake until the cake breaks free easily from the mold. Allow to cool on a wire rack.

Cut the cake in two (or into more pieces) and spread jam between the layers. The top of the cake can be covered with glaze and decorated with more jam, berries, candied fruit or nuts. Cut into thin slices with a sharp knife.

Read more: How to ring in the New Year like a Russian>>>

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox