The Roma and Russian literature: Centuries of association

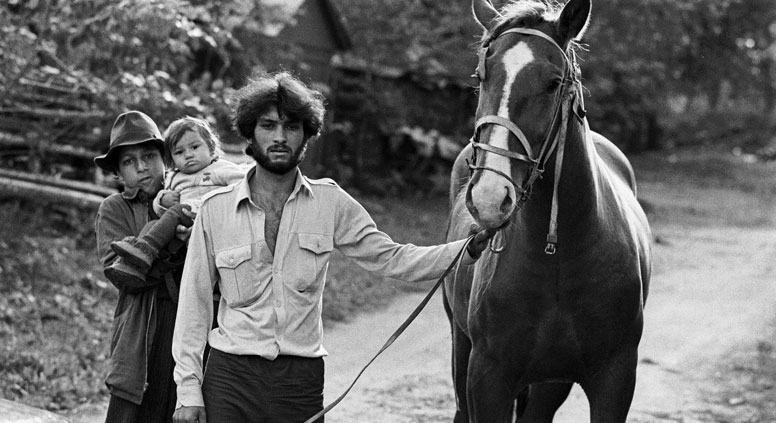

Russian Gypsies are first mentioned in 18th-century historical texts. Source: PhotoXpress

The World Romani Congress in London on April 8, 1971 was attended by 23 representatives from nine countries. It declared the Romani people a “single non-territorial nation” and adopted their flag and anthem.

Persecuted and misunderstood

Before the 1990 publication of Efim Druts and Alexei Gessler’s book “Gypsies”, many Russians did not know the true, complex history of the Romani people. This book dispelled many myths, but misconceptions are still widespread today.

Historically, both Europeans and Russians believed that the Roma originated in Egypt (hence their English name Gypsy) and were descended from pharaohs. To this end, Alexander Kuprin’s 1911 short story about Gypsies was called “Tribe of Pharaohs”.

In fact, back in 1844 the German linguist August Pott proved that the Romani people originated from India. They most probably left the subcontinent in the middle of the 5th century.

This exodus marked the start of the long-suffering Roma people’s difficult journey throughout Europe. They were treated differently wherever they went; in Greece, for example, they were welcomed, while they were persecuted and all but annihilated in other countries.

In 1633, a decree was issued in Spain threatening Gypsies with execution unless “they don ordinary clothes, forget their language and even their names.” A law passed in England by Queen Elizabeth I in 1562 criminalised people who even stayed with Gypsies once, as well as the Gypsies themselves.

Gypsies in the Russian Empire

Russian Gypsies are first mentioned in 18th-century historical texts from Anna Ioannovna’s reign, when a decree was issued regarding the duties to be levied from them. Her successor, Elizaveta Petrovna, issued a decree banning Gypsies from St. Petersburg and its environs. However, even the toughest restrictions imposed on Gypsies in Russia pale in comparison with what was happening in Europe, where a decree stating that “every Gypsy encountered on the road must be hanged” could easily be issued.

All in all, the story of the Roma people’s diaspora is a complex, exciting and largely tragic tale. One thing is clear: they have succeeded in maintaining their identity.

Portrayals in Russian literature

Gypsies have featured prominently in world literature, often becoming protagonists, as in Victor Hugo’s “Notre-Dame de Paris” or Prosper Mérimée’s “Carmen”. Russian literature also owes a great deal to Romani culture, and almost all major Russian authors have included Gypsies in their work.

Gypsy values have become an integral part of Russian literature. The two cultures were drawn to each other by their concept of freedom (volya), which is very different from the European concept of liberty.

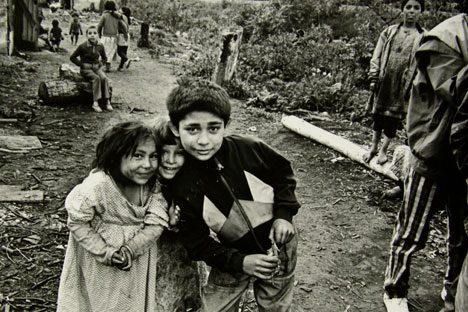

In the 18th century Gypsies were banned from the capital - St. Petersburg - and its environs. Source: PhotoXpress

Interestingly, the first truly outstanding artistic work about Gypsies in Russia – Pushkin’s poem “The Gypsies” – also established the ethical foundations of future Russian literature. An old Gypsy man tells the main character, Aleko, who has killed his Gypsy lover: "Leave us, you proud, disdainful man!/ We are savage, and we do not have laws,/ But we do not torture, and we do not kill. /We have no need of blood or groans/ But to live with a murderer we have no wish."

That statement is just a few steps removed from Dostoyevsky’s famous utterance: "Humble yourself, oh haughty man."

Maxim Gorky’s first work, “Makar Chudra”, also begins with an old Gypsy man pondering freedom: “So you are walking? This is good! You have chosen a glorious path for yourself, falcon. That’s the way to do it: walk and watch and when you have seen enough, lie down and die - and that’s it!”

Russian poetry and songs have also had a complex interconnection with Gypsy culture. The poets Afanasy Fet, Apollon Grigoryev, Alexander Blok and Nikolai Zabolotsky all had significant Romani influences. After a few drinks, Russians often start singing "My bonfire is alight in the fog…” by Yakov Poklonsky, while the famous Soviet film “A Cruel Romance”, based on a play by Alexander Ostrovsky, produced a hugely popular hit song called “Follow a Gypsy star”. Few people are aware, however, that its lyrics are in fact based on a Rudyard Kipling poem.

Perhaps equally surprising for ordinary Russians is that the instantly recognizable song “Valenki”, with its refrain “during the frost I went barefoot to my sweetheart,” is in fact an old Gypsy song based on ditties from Saratov Region. The fact that “Valenki” became one of the most popular songs on the front line during World War II shows just how entwined Gypsy culture and traditions have become with Russian culture itself.

First published in Russian in Rossiyskaya Gazeta

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox