Elbe Day: A handshake that made history

Seventy years ago Soviet and American troops cut through the Wehrmacht divisions and met in the middle of Germany near the town of Torgau, 85 miles from Berlin, on the Elbe River. Source: UllsteinBild/Vostock-Photo

For years, Soviet troops had been inching slowly westward, pushing Nazi troops back all along the Eastern Front. On June 6, 1944, D-Day, American and British troops opened a second front in Europe and began fighting the Nazis on the ground from the West.

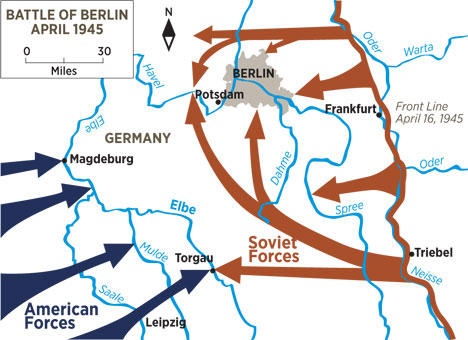

Finally, on April 25, 1945, Soviet and American troops cut through the Wehrmacht divisions and met in the middle of Germany near the town of Torgau, 85 miles from Berlin, on the Elbe River. The allied forces had effectively cut Germany in two.

Source: Open sources

That Soviet and American troops would meet in this general area was known, and signals had even been worked out between the allied leaders at Yalta to indicate to the troops on either side that they were friendly. But the actual meeting itself was decided by fate. The moment, which came to be known as the Meeting on the Elbe, portended the end of the war in Europe, which came less than two short weeks later, when the Red Army stormed Berlin.

Lt. Bill Robertson of the 273th Regiment of the 69th Infantry Division, driving on the morning of April 25 into the town of Torgau, knew that he might encounter Soviet troops, and knew he should greet them as friends and allies – Gen. Courtney Hodges, Commander of the First U.S. Army, had told his men to “Treat them nicely.” But Robertson was not prepared to carry out the protocol that U.S. President Franklin Roosevelt, Soviet Leader Joseph Stalin and British Prime Minister Winston Churchill had worked out several months before in Yalta.

The first American soldiers to make contact were to fire a green-colored star shell – the Soviets, a red one. Robertson and the three men in his patrol decided the best way to show they were Americans was to present an American flag. As they didn’t have a flag, they found a white sheet and painted it as best they could to look like the stars-and-stripes.

Soviet Lt. Alexander Sylvashko was skeptical at first that Robertson and his men were Americans. He thought the four men waving a colored sheet were Germans playing a trick on the Soviet troops. He fired a red star shell, but did not receive a green one in return.

Sylvashko sent one of his soldiers, a man named Andreev, to meet Robertson, in the center of a bridge crossing the Elbe. The two men awkwardly embraced and made the hand signal of “V for Victory.”

The following day, a huge ceremony was held on the spot with dozens of soldiers from both sides. They swore an oath, in memory of those who had not made it so far:

“In the name of those who have fallen on the battlefields, those who have left this life and in the name of their descendants, the way to war must be blocked!”

On this partially destroyed bridge over the Elbe, the Soviet and American soldiers built a new one, between countries — a bridge of friendship.

That day, the soldiers met as comrades-in-arms, embraced each other, and exchanged buttons, stars and patches from each other’s uniforms. Later, this exchange of “souvenirs” was carried out at the highest levels. Officers exchanged their service weapons.

Soviet Marshal Ivan Konev presented U.S. General Omar Bradley with his war horse, a magnificent Don stallion; Bradley presented Konev with the Legion of Merit – and also gave him a jeep. Marshal Georgy Zhukov, the top Soviet general, awarded Supreme Allied Commander Dwight D. Eisenhower the highest honor of the Soviet Union, the Order of Victory. Eisenhower gave Zhukov the Legion of Honor.

Marshal Georgy Zhukov, the top Soviet general and Supreme Allied Commander Dwight D. Eisenhower. Source: RIA Novosti

Eisenhower, who loved Coca-Cola, shared a drink with Zhukov. The Soviet commander liked it so much a special version of Coca-Cola, White Coke, was made for him. The drink was colorless so that it would look like Zhukov was drinking vodka.

This exchange of culture and customs was indicative of the spirit of the Meeting on the Elbe.

In 1988, a book called Yankees Meet the Reds came out in both English and Russian, commemorating the meeting on the Elbe River. In it American Lieutenant Colonel Buck Kotzebue made an interesting observation: “I think that all soldiers definitely have something in common. They understand the meaning of war. And if we could let them choose, there would be no war. Yes, you can doubt the spirit of Elbe. You can say that these are just dreams about the impossible. But I think that it is necessary to dream about the impossible. Only then will it become possible.”

Also in 1988, the first monument to the Meeting on the Elbe was dedicated – a plaque was mounted on the spot in Torgau where the meeting took place.

A memorial in Arlington Cemetery in Washington also commemorates the spirit of Elbe. It is a bronze plaque, immortalizing the historic handshake between Soviet and American soldiers with an optimistic sign reading: “The spirit of Elbe lives on and conquers.” Wreath laying ceremonies take place at the cemetery each year on April 25 with military bands playing the national anthems of Russia and the United States.

With time, the memory of that powerful moment on the Elbe has faded, but it is necessary to preserve the recollections of that profound meeting.

In Moscow, the Spirit of the Elbe organization in partnership with the Veteran’s Union, carries out educational activities and conferences dedicated to the anniversary of the allies’ meeting.

The 1949 film “Meeting on Elbe” is still popular in Russia.

Encounter at the Elbe (1949) was directed by Grigori Aleksandrov and Aleksey Utkin, with music by Dmitri Shostakovich. Source: Youtube

It begins with the “Song of Peace,” composed by Dmitri Shostakovich. The film ends with the words of the two protagonists, a Soviet and an American: “The friendship between the people of Russia and America is the most important issue that mankind now faces.” With Shostakovich’s soulful music playing in the background, these words still have a significant impact, especially today.

Joseph and Jonn Beyrle. Source: Press photo

American and Soviet soldiers both fought against Hitler’s armies, but mostly from different front lines. One man, however, embodied the Allies’ united front against the Nazi threat.

Joseph Beyrle (1923-2004) is the only American known to have served in the Red Army. A paratrooper who carried out several missions in occupied France before the Allied invasion, Beyrle lost contact with his unit on D-Day and was captured by German forces a few days later. He spent six months in German P.O.W. camps before being transferred to the Stalag 3-C camp in what is now Poland. Beyrle escaped from the camp, headed east, and found his way to part of the Second Belarussian Front, which was making its way westward towards Berlin.

He convinced the soldiers he met to take him on, and he fought for several weeks with a Soviet tank battalion before being seriously wounded in a German bomber attack. Beyrle returned home to Michigan and — like many combat veterans — didn’t speak much about the war, according to his son, John Beyrle, a career diplomat who served as U.S. Ambassador to Russia from 2008-2012. But eventually his unique story came out.

Today Beyrle is considered one of the very few American soldiers to have fought in both the U.S and Soviet Armies against Germany in WWII. Beyrle received medals from both U.S. President Bill Clinton and Russian President Boris Yeltsin at a Rose Garden ceremony on June 6, 1994, marking the 50th anniversary of D-Day.

John Beyrle told RBTH that his father’s experience with the Russian troops was transformative. “The way they [the Soviet soldiers] treated him, gave him food, believed his story and even trusted him with weapons left a stong impression on him for the rest of his life,” John Beyrle said.

At the opening of an exhibit in Moscow honoring his father on May 8, 2010, John Beyrle said that his father’s experience taught him what the war meant to Russians. “Having been through Poland and Eastern Europe, my father — and through him my entire family —understood what the cost of the war was to the Russians,” his son said. “I’d say we knew more about their role in World War II than most Americans. And Americans should know more about Russia’s role in the war, just as, I would say, Russians should know more about America’s contribution.”

Alexander Potemkin is the executive director of the American-Russian Cultural Cooperation Foundation in Washington, D.C., and was a cultural attaché both to the Soviet Union and the Russian Federation.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox