A screenshot from "The Road to Berlin" movie. Source: Kinopoisk.ru

Mikhail Chiaureli's The Fall of Berlin (1949) is perhaps the most curious Soviet film about World War II, especially because its propagandistic shamelessness and purportedly documentary style had no equals in world cinema. In the film, Joseph Stalin is present in practically all spheres of life of the Soviet individual, including the intimate side: He listens to a steelmaker's confessions about a girl he is in love with while digging in a tree in a garden, he personally discusses with Marshal Zhukov the plan to take Berlin and in the end he flies to the occupied city in order to congratulate his people and other nations on their liberation from the 20th century plague. Out of all this, the most likely episode is the sowing of the tree, however, that is also a matter of debate. It is known that Stalin flew abroad only once: to Tehran.

A poster of The Fall of Berlin movie. Source: Kinopoisk.ru

The fate of The Fall of Berlin reflects the changing political situation. While in 1950 it was one of the three Soviet blockbuster films, after Stalin's death in 1953 it was removed from the movie theaters.

The thaw that followed Stalin's death and the temporary distancing from war paved the way for films that are still considered classics of world cinema. In 1957 Mikhail Kalatozov's The Cranes are Flying was released. This film does not have a party and a government, but is the private story of one girl whose boyfriend does not return from the front. The film received the Palme d'Or in Cannes, and the famous scene depicting the death of Boris (played by Alexei Batalov) was included in all the textbooks thanks to the innovative technique of director of photography Sergei Urusevsky. It seemed that the country would now open to the world, since the story told in the film is universal. However, the news of the triumph in Cannes went almost unnoticed in the USSR, while First Secretary Nikita Khrushchev labeled the film's heroine a slut.

Two years later Grigori Chukhrai's Ballad of a Soldier came out, repeating Kalatozov's success. It received the special jury prize at the Cannes Film Festival and another hundred awards around the world, even an Oscar nomination for best screenplay.

By the beginning of the 60s the theme of war, which was still not that far away for its consequences to have been forgotten, but not distant enough to be viewed in a complex manner, became the main subject of Andrei Tarkovsky's first feature-length film, Ivan's Childhood. The director took the theme of war out of the realm of ideology and drama and placed it in one of psychology, into the world of a child, who at the age of 12 becomes a partisan.

A screenshot from the "Ivan’s Childhood" movie by Andrei Tarkovsky. Source: Kinopoisk.ru

Tarkovsky's film generated a whole movement of auteur cinema in Soviet art. The state financing system, which did not depend on revenues, could permit itself to support the talented director, especially since the young Tarkovsky was doubtlessly worth the risk of disagreeing with the party ideology committee. In 1962 Ivan's Childhood received the Golden Lion in Venice.

Even though directors were oppressed during the era of stagnation, they were able to make auteur films about the war in the horror genre, which was outlandish in the USSR. Elem Klimov's Go and Watch (1985), which came out before perestroika, was an example.

With the end of the era of state financing the general quality of Russian cinema went into drastic decline, especially since at the time, in the 90s, Hollywood, and Steven Spielberg in particular, intercepted the initiative and made the two most important war movies of the age: Schindler's List and Saving Private Ryan. The latter became a standard for war films, which are now shot as action movies with some emotional scenes, but mostly naturalistic action.

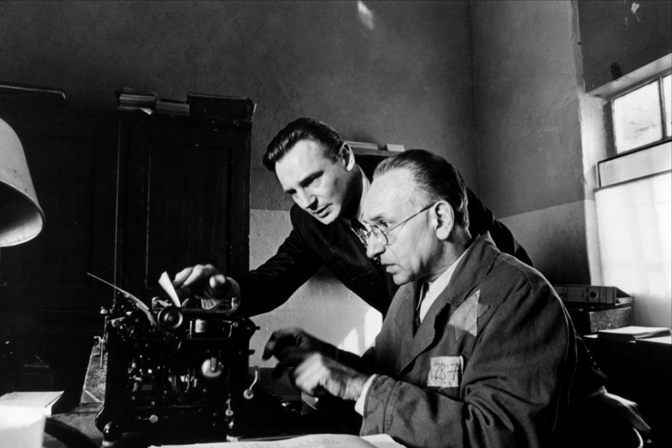

A screenshot from the Schindler's List movie. Source: Kinopoisk.ru

In Russia no one had these budgets anymore and Nikita Mikhalkov's sequels to Burnt by the Sun proved that the modern audience no longer felt the old approach to cinema as a "great art," as it was in the Soviet consciousness. Fyodor Bondarchuk's Stalingrad (2013) became a hit precisely for the reason that it is filmed like a Hollywood action film with special effects, and it is rather patriotic and universal, at least for Asian filmgoers.

The current system of cinema financing is making commissions on the eve of the 70th anniversary of Victory Day. This year there is an incredible number of films about the war, like never before. Soon Russian movie theaters will see the release of The Battle for Sevastopol, the remake of The Dawns Here Are Quiet and The Road to Berlin, which hopes for state financing, telling the story of the forgotten companionships formed between soldiers from different Soviet republics.

The Battle for Sevastopol - International Trailer (2015). Source: YouTube

The Road to Berlin is far from the propagandistic absurdity of The Fall of Berlin, which means that we have come a long way since 1949 – both as viewers and as citizens.

Gennady Ustian is a film critic and chief editor of Time Out Moscow.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox