Prolific artist who filled Hermitage gallery deserves more attention

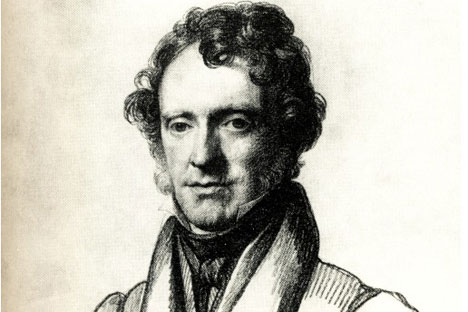

George Dawe, by Carl Christian Vogel von Vogelstein (1828).

wikipedia.orgAsked to tot up a mental list of famous British artists, it’s unlikely that George Dawe will be among your Hockneys, Gainsboroughs, and (heaven forbid) Hirsts. Despite the international renown and favorable opinion of critics he garnered over the course of his lifetime (1781-1829), the name of George Dawe is seldom heard, left instead to the void of history and the occasional mention on a BBC Radio 4 graveyard slot.

Fame is, of course, a fickle friend, showering artists with glory and sweet nothings one moment, leaving them for dead the next. But what is so bewildering in the case of George Dawe, is that against all odds, fame has evaded him. Few 19th century artists can boast such a large output, match the stature of his sitters, or claim an equal footing in the longevity of the exposure of their works. But the comparison is somewhat unfair; after all, how many painters have an entire gallery within one of the world’s most prestigious museums, dedicated to their oeuvre?

Imperial attention

Dawe, who was the son of engraver and part-time satirist, Philip Dawe, came to the attention of the Imperial Court in the autumn of 1818 while traveling with the Duke of Kent, in whose retinue he found himself in Aachen, where the first congress of the Holy Alliance was taking place to discuss the fate of post-Napoleonic Europe. Impressed by the speed and deftness with which the 37 year-old painted Prince Pyotr Volkonsky, Tsar Alexander I invited Dawe to St. Petersburg, as the man who would realize his dream of a grand hall dedicated to the victory over Napoleon.

By the autumn of 1820, Dawe, who had been living in what was then the Russian imperial capital for nearly eighteen months, had completed 80 of the 342 portraits intended for the gallery. Along with several paintings that he had brought with him from England (including portraits of Princess Charlotte and the Duke of Kent), Dawe exhibited five of the half-length 1812 portraits at the Imperial Academy of Arts. Critical opinion was highly favorable, Russian artist and writer Pavel Svinyin positively bristling with enthusiasm, saying, “The likeness in his portraits is extreme, their effect staggering, the faces emerge from the frames…these are the works of a most original talent.”

Military Gallery of the Winter Palace, State Museum of Hermitage, St. Petersburg. Source: Getty images

Again, what is highlighted in particular is the speed of Dawe’s compositions, crafted by “the work of a hand that does not like to control or check itself.” Svinyin’s own ebullient hand was, however, to be checked to some degree by his aversion to the characteristically English malaise of expression within the works: “From the effort to be expressive the English artist has descended to extremes… such, alas, is the defect of the works of the English Artists, or rather the general fault of the English School.”

Triumphant exhibition

In spite of the sins committed by his homeland, the exhibition was a triumph and Dawe was made an ‘Honorary Free Associate of the Academy of Arts’. Now in increasingly high demand, and being paid roughly 1000 rubles for each half-length portrait, Dawe received an income at a level enjoyed by no contemporary Russian artist. Immersed in the social circles of the Russian elite, he was the subject of a poem by Pushkin (“Why does your marvelous pencil draw my African profile?”) and a guest of honor at the coronation of Nicholas I in 1826.

The workload was, however, to prove to be too much for Dawe who, in addition to his Military Gallery tasks, was receiving dozens of private commissions each year. It was thus decided in 1826, with roughly two-thirds of the 1812 corpus completed, that the artist should take on two assistants: Wilhelm Golicke (“a poor and meek man who did not know his own worth”) and Alexander Polyakov, a self-taught serf, who had been sent by his owner to study under Dawe in 1822.

In the autumn of 1827, Dawe’s works were once again exhibited at the Academy of Arts. Now, with nearly all of the portraits for the gallery finished (and the gallery itself completed and already furnished with the majority of Dawe’s paintings), the exhibition was the summit of Dawe’s exploits in Russia, showcasing more than 150 canvasses, including images of such military geniuses as General Pyotr Bagration and Prince Dmitry Golitsyn. While most reviews erred on the side of laudatory enthusiasm for the English painter (“His industriousness is inferior only to his talents”), the champion of his early Russian years, Pavel Svinyin noted with distaste “the haste with which some [portraits] are painted”, and the low quality of some of his most recent works.

Such were the first inklings of Dawe’s impending demise. A portraitist whose unique talent lay in the speed with which he could transpose his subjects onto canvas, became a victim of the spoils that that skill afforded him. In short, George Dawe became too greedy. In the same year as the exhibition at the Academy of Arts, the Society for the Encouragement of Artists received a letter from Dawe’s assistant, Alexander Polyakov, complaining of his mentor’s malpractice. The note, which was most likely drawn up with the help of Svinyin, details Dawe’s pitiless exploitation as well as his systematic swindling of clients, passing off the work of his assistants as his own. What is more, according to Polyakov, several of the portraits appearing in the Military Gallery itself were painted not by Dawe, but by his assistants, without accreditation.

Fall from grace

In response, the Society requested Polyakov’s liberation from serfdom and, in a special address to the Tsar, informed him of Dawe’s “reprehensible actions”. The subsequent downfall of the engraver’s son was rapid; he hastily quit Russia in early 1828 and died in the October of the following year at his sister’s house in London.

No one is all bad, and on his deathbed Dawe bequeathed to his “poor and meek” assistant Wilhelm Golicke a large sum to ensure him a lifetime pension. And though perhaps a flawed man in some respects, he was, as an artist, a virtuoso. Upon his visit to the Military Gallery in 1859, Professor Charles Piazzi Smyth noted, “his English country may well be proud of Mr. Dawe, and Russia not ungrateful.”

Read more: 5 English portraits you shouldn’t miss at the Hermitage

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox