Karelian dream: The foreigners who have made their home in Russia’s north

Canadian linguist Lloyd Morin believes that unlike residents of large cities who have lost touch with nature, for people in Karelia, nature is still an important part of their lives. Photo: Lloyd Morin on the lake.

Personal archiveWith the fall of the Iron Curtain in 1989 and the subsequent collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, tourists and emigrants from the former USSR became a relatively common sight in Europe and America. However, there was also movement in the other direction too, with foreigners coming to discover Russia.

Most of them, of course, came as tourists, but there were also those who moved to Russia for good. The majority, especially in the first years after perestroika, preferred large cities, mainly Moscow and St. Petersburg. However, by the late 2000s, expats were no longer a rarity in the Russian provinces either.

There is a particularly high number of foreigners living and working in Russian regions near the borders, like Karelia, the large forested republic adjoining Finland. According to the local directorate of the Federal Migration Service, several thousand foreigners from all the world’s continents are either permanently resident in Karelia or currently studying or working there.

The majority are, of course, from neighboring Finland, but the region is also a temporary or permanent home to nationals from Germany, the U.S., Canada, Japan, China, Eastern Europe, the Middle East, Africa and South America.

Airiness, space and coziness

Perhaps the best-known of Karelia’s residents who was born and grew up in Europe is the Polish author Mariusz Wilk. A man with a checkered personal history, Wilk was press secretary and confidant to Poland’s first freely-elected president Lech Walesa, fought against Poland’s communist authorities, worked as a journalist and war correspondent, and then found his love and made his home in Karelia, in the small village of Kondoberezhnaya on the shores of Lake Onega.

Here Wilk leads a secluded life with his wife and daughter. His wife Natalya is from the capital of Karelia, the city of Petrozavodsk. Like her husband, she takes a keen interest in Russian history and antiques. Wilk writes books about Russia’s north with a particular emphasis on those living alongside him, ordinary Russians from the villages beyond Lake Onega.

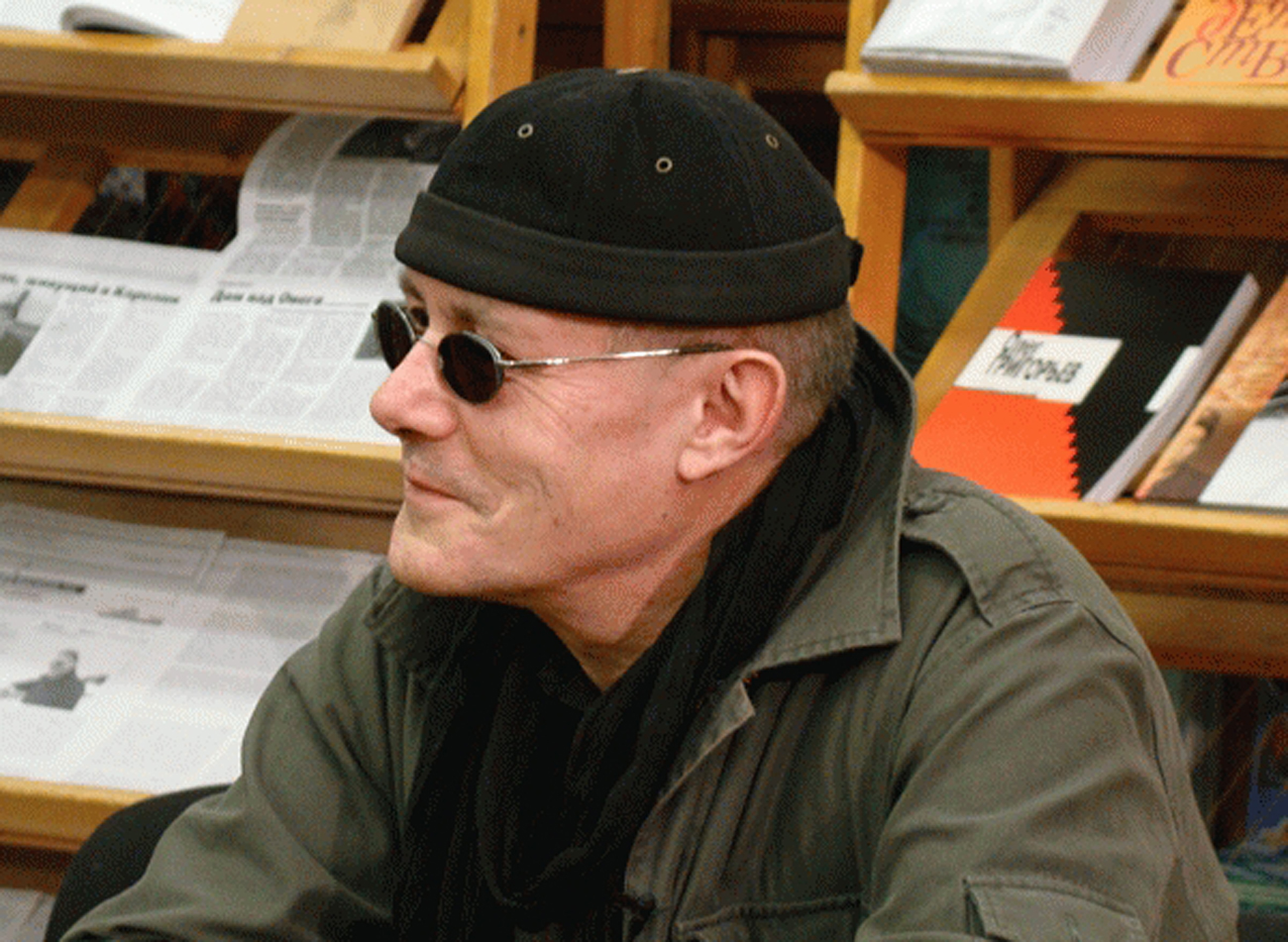

Wilk writes books about Russia’s north with a particular emphasis on those living alongside him, ordinary Russians from the villages beyond Lake Onega. Photo: Polish author Mariusz Wilk. Source: Personal archive

Wilk writes books about Russia’s north with a particular emphasis on those living alongside him, ordinary Russians from the villages beyond Lake Onega. Photo: Polish author Mariusz Wilk. Source: Personal archive

He also often comes to Petrozavodsk, where he gives master-classes for first-time writers and shares his plans for the future.

“I live between Petrozavodsk and my village, so I don’t feel like a stranger in the city. Furthermore, soon my daughter will be starting school, so I have already bought a flat in Petrozavodsk, where I am planning to live in my retirement,” said Wilk at a presentation of his book House by the Lake in the city in January 2015, adding that Petrozavodsk was not only the place where his daughter was born but also the place where he had chosen to spend the autumn of his life.

“Why? Because to me it is the best northern city in terms of how beautiful and compact it is. Arkhangelsk, Murmansk, St. Petersburg are all inferior to it. The combination of a small city and a huge lake gives airiness and space and at the same time coziness,” said Wilk.

Life in Russia is like ‘running in honey’

Love is what brought German businessman Thomas Heinrich to Karelia too. Five years ago, he met a woman from Petrozavodsk on the internet, came to visit her and has remained there ever since. Heinrich admits that, having been brought up with traditional German values and love of order, he sometimes finds it hard to adapt to a Russian way of life. But he is not losing heart: He runs a business and is building a house on the lake.

German businessman Thomas Heinrich at a construction sight. Source: Personal archive

German businessman Thomas Heinrich at a construction sight. Source: Personal archive

“Generally speaking, of course, things here are not as calm and quiet as back home. After all, not every German would make up their mind to move here. There is a fear of losing one’s usual lifestyle,” he said.

“But I am ready for a fight and ready to face challenges, which means I am ready to live in Russia. I compare it to running in honey … it is sticky, it is hard, you get stuck but you must carry on. Fortunately, I have strong legs,” laughed Heinrich.

In Karelia, Heinrich has been able to fulfil his childhood dream – to buy a Russian Niva jeep. Although in terms of comfort this vehicle is no competition to its German counterparts, on the plus side, it is very cheap to run and is very good on forest roads.

Besides, Heinrich has people in his life for whose sake he is prepared to overcome all difficulties. The young German-Russian couple now have a daughter named Mia.

In Karelia, Heinrich has been able to fulfil his childhood dream – to buy a Russian Niva jeep. Photo: German businessman Thomas Heinrich. Source: Personal archive

In Karelia, Heinrich has been able to fulfil his childhood dream – to buy a Russian Niva jeep. Photo: German businessman Thomas Heinrich. Source: Personal archive

A hair’s breadth from Canada

Young Canadian linguist Lloyd Morin was brought to Karelia by his love of science and the Karelian language (close to Finns and Estonians, Karelians are a Finno-Ugric people resident in Finland and in the Russian region of Karelia). Back home, Morin went to an art school and then studied the Russian language, Russian history and literature. In 2010, he came to St. Petersburg on a student exchange program and in 2013 continued his studies in the Finnish town of Joensuu, not far from Karelia, in a new subject, sociolinguistics.

Canadian linguist Lloyd Morin was brought to Karelia by his love of science and the Karelian language. Photo: Lloyd Morin. Source: Personal archive

Canadian linguist Lloyd Morin was brought to Karelia by his love of science and the Karelian language. Photo: Lloyd Morin. Source: Personal archive

Joensuu is one of the leading Finnish centers of Karelian studies and Morin became so interested in the Karelian language that in 2014 he moved to Petrozavodsk across the border and began to study it in earnest. Today, he probably knows Karelian better than the majority of the local population.

The young Canadian likes it in Karelia very much and says the region’s nature is very similar to that of his home country: “The climate is much colder here, but I love winter sports, so that’s an upside for me,” he said.

In 2010, Lloyd Morin came to St. Petersburg on a student exchange program and in 2013 continued his studies in the Finnish town of Joensuu, not far from Karelia, in a new subject, sociolinguistics. Photo: Lloyd Morin. Source: Personal archive

In 2010, Lloyd Morin came to St. Petersburg on a student exchange program and in 2013 continued his studies in the Finnish town of Joensuu, not far from Karelia, in a new subject, sociolinguistics. Photo: Lloyd Morin. Source: Personal archive

Morin believes that unlike residents of large cities who have lost touch with nature, for people in Karelia, nature is still an important part of their lives. “That’s why I find it comfortable living here,” he said.

Read more: Veps: Finno-Ugric people with ancient roots>>>

Subscribe to get the hand picked best stories every week

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox