Big on Bolshevism: London marks anniversary of the 1917 Russian Revolution

February Revolution 1917.

Archive PhotoLying on scaffolding beds above the stage, blanketed figures cough and groan. A percussive dripping lends the smoky, brick-walled room an air of dereliction. This is the opening of Maxim Gorky’s most famous play, The Lower Depthsat The Arcola Theater; its destitute characters gradually reveal their richly varied lives and personalities and discover an unexpectedly moving companionship in shared misery.

Books, films, concerts

UK responses to the centenary began late last year with screenings at cinemas in Soho and Bloomsbury ofRevolution: New Art for a New World. A partially dramatized documentary, featuring Tom Hollander as the voice of Kazimir Malevich and Matthew Macfadyen as the voice of Lenin, the film shows artists inspired, and later crushed, by political changes.

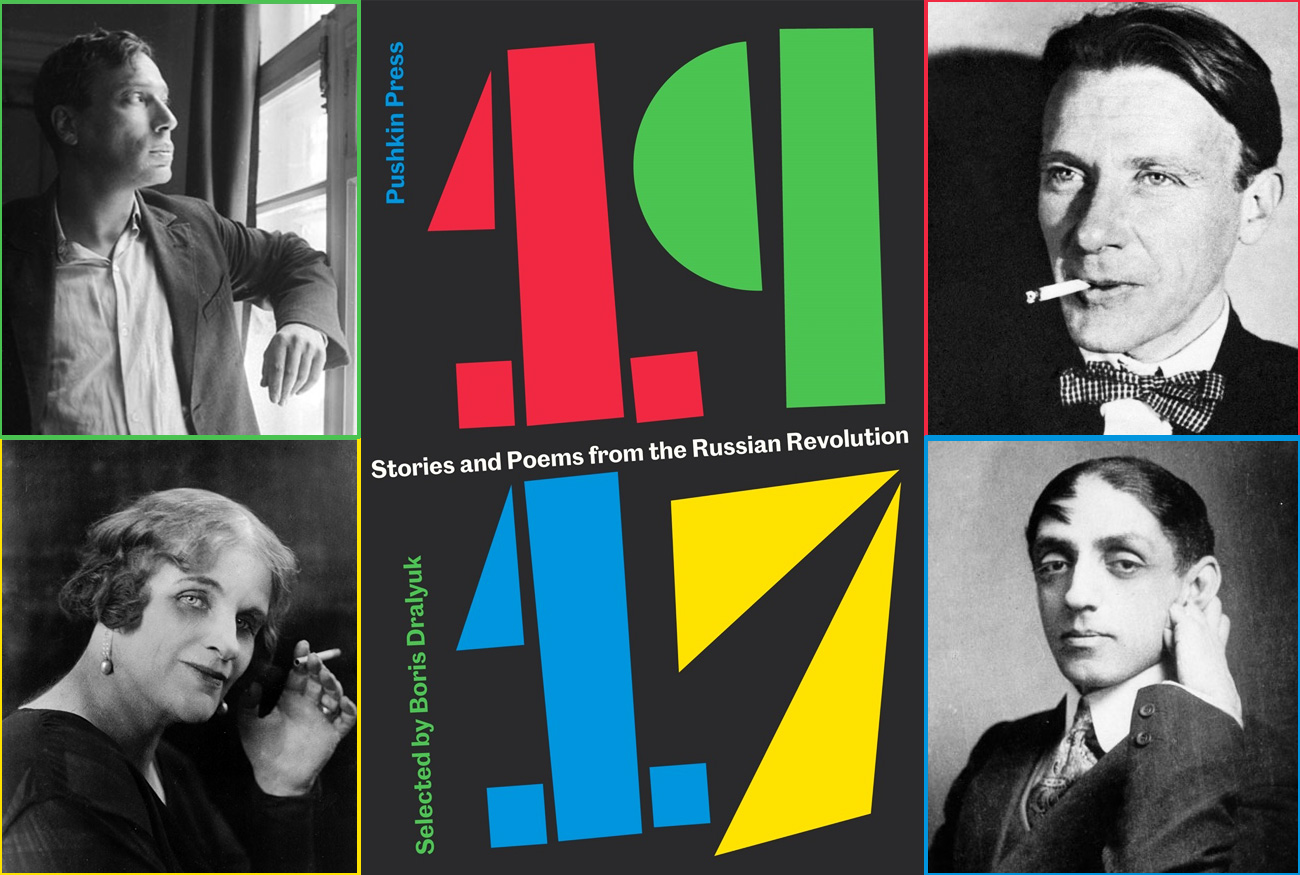

Pushkin Press published 1917 Stories and Poems from the Russian Revolution and there are more books coming, including historian Robert Service’s The Last of the Tsars: Nicholas II and the Russian Revolution, out in February. Last November, Douglas Smith’s new blockbusting tome Rasputin shed light on the paradoxical prophet of late-imperial Petersburg.Soon afterwards, London’s Russian cultural center Pushkin House launched a fifteen-month collaborative venture, Project1917. As part of the project, you can talk to a Rasputin chatbot online (and get answers from the mad monk’s letters). Pushkin House director, Clem Cecil said: “The events of 100 years ago profoundly affected the course of world history”, calling Project17 a “playful, yet serious way to become immersed in those events.”

Dash Arts, a London-based arts center with an international perspective, in a series of events called REVOLUTION17, is dedicating the year to “vibrant and urgent performance from the turbulent Soviet century”. They are reviving their pop-up summer dacha and – in the meantime – planning lively gigs, talks, readings and films, including Sergei Eisenstein’s Battleship Potemkin.

A final “explosion” of theater, music and art will start in October, the culmination of five years that Dash Arts have spent immersed in the cultures of the post-Soviet countries. Also in October, the Barbican is planning a screening of Eisenstein’s 1928 film October: Ten Days that Shook the World; their program describes the Bolshevik Revolution as an event “whose far-reaching consequences are still being felt to this day”.

Art and the avant-garde

London’s Royal Academy will be jumping on the anniversary bandwagon in February with a new exhibition called Revolution: Russian Art 1917–1932, featuring crowd-pleasing modernists like Chagall, Kandinsky and Malevich together with socialist realist works by Vera Mukhina or Alexander Deineka.

Boris Kustodiev’s painting 'Bolshevik' (1920)

depicts how the

Revolution was

made by the nation / RIA Novosti

Boris Kustodiev’s painting 'Bolshevik' (1920)

depicts how the

Revolution was

made by the nation / RIA Novosti

February also sees the launch of Calvert 22’s “year-long program of events” marking the centenary in partnership with the Hermitage and culminating in a first solo UK exhibition of works by Moscow conceptualist Dmitri Prigov. As usual, the Shoreditch-based gallery are taking a thoughtful look at the idea of revolutionary art.

Samuel Goff, a Slavonic Studies researcher at Cambridge, writes in the Calvert Journal: “There is still something hackneyed about the artistic vocabulary used to denote the world-changing events of one hundred years ago.” He suggests that historians look beyond the established clichés of 20th century Russian art: “When visualizing 1917, we should all remember that we’re dealing with a revolution, and try turning things on their heads for once.”

Myths and (post)-modernists

In April, the British Library attempts to do just that with an exhibition subtitled Hope, Tragedy, Myths, promising: “A fresh look at the Russian Revolution” and using items like Nicholas II's diary and a draft of Trotsky’s speech to recount “the multi-layered and complicated history with an unbiased eye.” Tate Modern joins the party in November, marking the centenary of the October Revolution, with exhibitions that Goff praises for their fuller range of artists and inclusion of pioneering later conceptualists.

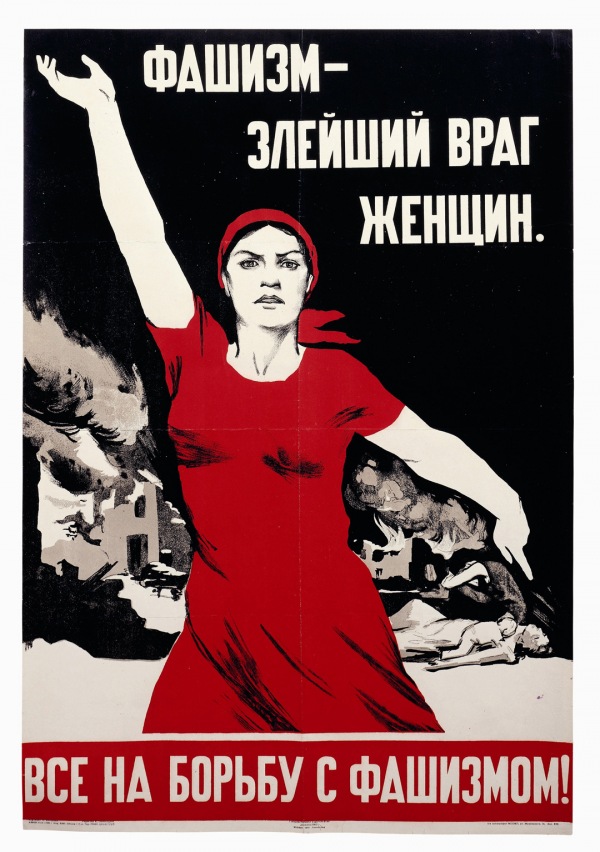

The Tate has an excellent collection of Russian modern art and will celebrate the “wave of innovation and design in Russia” with two major shows. Red Star Over Russia will use rarely seen posters and photographs to explore the “unique visual identity” created by Russian and Soviet artists between the first 1905 revolution and the death of Stalin in 1953”.

Nina Vatolina Fascism – The most evil enemy of women;1941 Tate / Image courtesy the David King Collection.

Nina Vatolina Fascism – The most evil enemy of women;1941 Tate / Image courtesy the David King Collection.

The second Tate exhibition has a contemporary angle, placing Ilya Kabakov’s late-Soviet works alongside installations made with his niece Emilia after the late 1980s (when he immigrated to the United States). The trendy new Design Museum in Kensington is marking the centenary with an exhibition of unrealized plans that “explores Moscow as it was imagined by a bold new generation of architects and designers in the 1920s and early 1930s.”

Theater and humanity

2017 is also set to be another bumper year for Russian drama in London. Chekhov is ubiquitous as ever; there is a more unusual outing for Alexander Ostrovsky’s Talents and Admirers in March, the UK premiere of Gorky’s The Last Onesin June, and the Questors theater group present a new thriller set in the perestroika-era. The Arcola will be following up The Lower Depths (which runs until Feb. 11) with a “Revolution” season, including a production of The Cherry Orchardwith the same cast.

In this first production, Gorky’s desperate characters achieve a compassionate sense of shared humanity that is powerful and timely. The Lower Depths was first performed in 1902, directed by Konstantin Stanislavsky for the Moscow Arts Theater and the director himself took on the role of beaten-up card sharp Satin (played here with faded rock star grandeur by Jack Klaff). “Humankind is not you or me,” explains Satin, with drunken benevolence in the final act, “humankind is you and me, and them … all rolled into one.” In a world with increasing global inequality, these are still revolutionary words.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox