Exiled in Moscow: When the USSR hosted Asian dissidents

Many pro-Soviet Afghans fled the mujahidin and moved to the USSR.

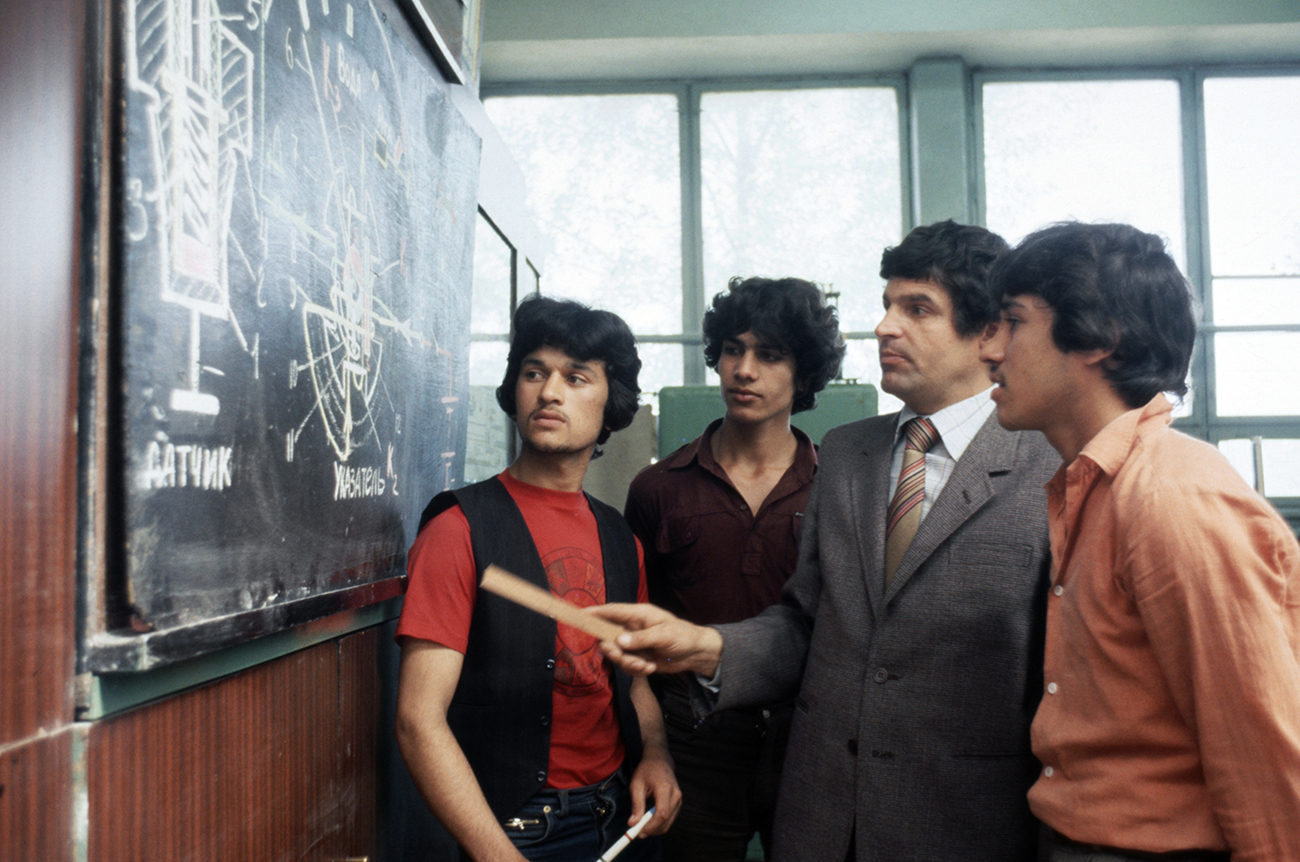

Yevgeny Nederya/TASSMoscow was a popular destination for Indonesian students in the late 1950s and early 1960s when the Soekarno regime pursued both socialism and close ties with the Soviet Union. By mid-1965 when General Suharto seized power in the country and began his purges on communists, several thousand Indonesian students were enrolled in various courses in Soviet universities.

“Faced with detention or execution if they returned home, Indonesian leftists and other dissidents who were scattered across some dozen states spanning the Sino-Soviet divide became unwilling exiles,” David Hill, Emeritus Professor of Southeast Asian Studies and Fellow in the Asia Research Centre at Murdoch University in Australia, wrote in a research paper titled ‘Indonesian Political Exiles in the USSR.’

“Many spent nearly half a century as exiles, struggling to survive first the vicissitudes of the Cold War and then the global transformations that came with the dissolution of the USSR in December 1991,” Hill wrote.

Very little official information is available on the actual numbers of Indonesians who chose to stay back in the Soviet Union, but the community that opposed Suharto’s rule in Indonesia stayed active through the 1970s when they received support from the Soviet authorities.

“I would estimate their numbers at around 2,000,” Alexei Dudnik, a historian from Moscow, now based in Bali, told RBTH. “Many married Soviet citizens and were later given citizenship…The ones who were determined to go home after the fall of Suharto’s regime were very active politically.”

Indonesian exiles in Moscow even managed to publish a Russian-Bahasa journal in the 1970s titled OPI, an abbreviation of the organization's title Organisasi Pemuda Indonesia. The journal focussed on Indonesian politics and the role of young people.

“The Indonesian Diaspora blended in with ease among the various ethnicities and nationalities of the Soviet Union,” Dudnik said. “Most people were given prolonged residence permits, as they weren’t viewed as a threat by the authorities.”

While those of Indonesian-Russian parentage stayed back in Russia after the collapse of the Soviet Union, there was a trickle of older generation people who returned to Indonesia.

“We had a large number of people approaching us for passports in the early 1990s, as many Indonesian exiles in Moscow were in a state of limbo with the fall of the Soviet Union,” Agosh Suharpanto, a former Indonesian diplomat based in Jakarta told RBTH. “This even included people in their 60s.”

Afghan traders and socialists

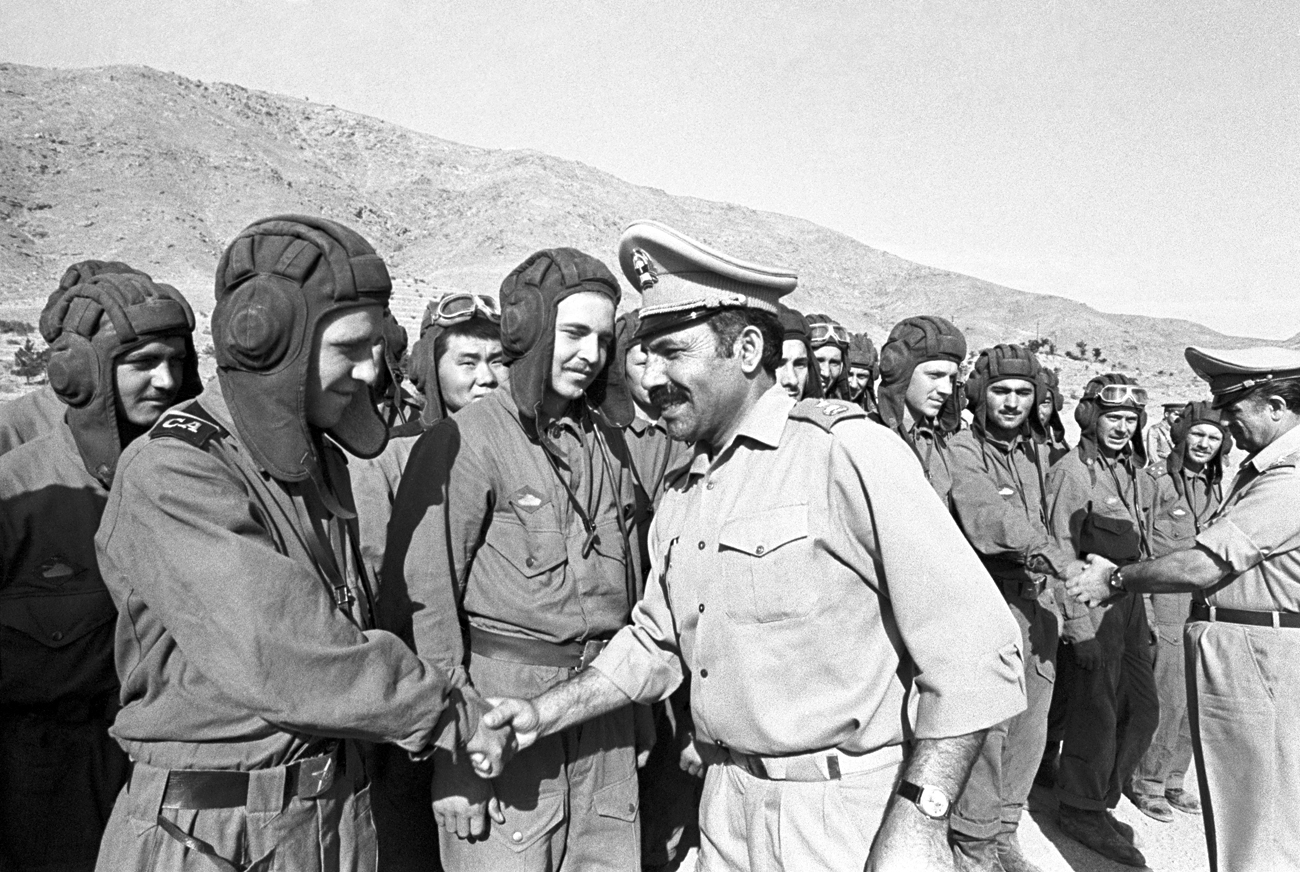

Another set of people that fled to the Soviet Union, fearing reprisal from anti-communist forces were Afghans who were loyal to the Russians.

Unlike the Indonesians, the Afghans moved to Moscow in the twilight of the Soviet Union, after the USSR withdrew from the country and the Najibullah regime collapsed.

“The rise to power of a divided array of mujahidin groups in Kabul also made life in Afghanistan dangerous, especially for individuals and their families who were associated with the pro-Soviet regime,” Magnus Marsden, Professor of Social Anthropology and Director of the Asia Centre at the University of Sussex, wrote. “As a result, many officials from that era left Afghanistan and established themselves as commodity traders dealing in a wide range of good across the former Soviet Union.”

According to Marsden, Afghans pioneered the import of low grade and cheap Chinese commodities, initially travelling to the city of Urumqi in Xinjiang and bringing the goods back in trucks to Moscow.

Another small wave of Afghan refugees started coming to Russia after 2001. The Afghan community in Russia is estimated to number around 150,000, according to a Reuters report.

Moscow has an Afghan mosque, bakery and even a television station. The two waves of immigrants have merged into one diaspora that is unlikely to be heading back to the war-torn country anytime in the near future.

“The USSR quietly provided refuge to a smattering of nationalities and for the most part, the idea was to eventually have idelogically friendly regimes in these countries in the future, an aim similar to that of the West,” Dudnik said.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox