Biting the bullet: How military service was avoided in Imperial Russia

'A recruit' by Ivan Repin (1879). / Source: Russian Museum

'A recruit' by Ivan Repin (1879). / Source: Russian Museum

Conscription of young Russian men for lifetime service began in 1699 during the rule of Peter the Great. The goal was to establish a standing army and increase its size for the emperor's many military campaigns. During the reign of Nicholas I, in the second quarter of the 19th century, the possibility to pay a substitute for one's military service was legalized in order to give new life to the recruitment system.

Aristocratic draft-dodging

Conscription significantly differed for the wealthy and the lower classes. Each nobleman had to serve in the military, but city dwellers and peasants, who unlike the aristocracy paid a direct poll tax, faced a specific form of recruitment. The local commune selected only some men between 20 and 35 years old who would spend the rest of their lives in the army.

The state was primarily interested in a specific number of future soldiers and their physical abilities. It didn't care how the commune selected them. Conscription was announced by a special decree nearly every year, but if Russia was in a serious war, conscription would be held several times a year.

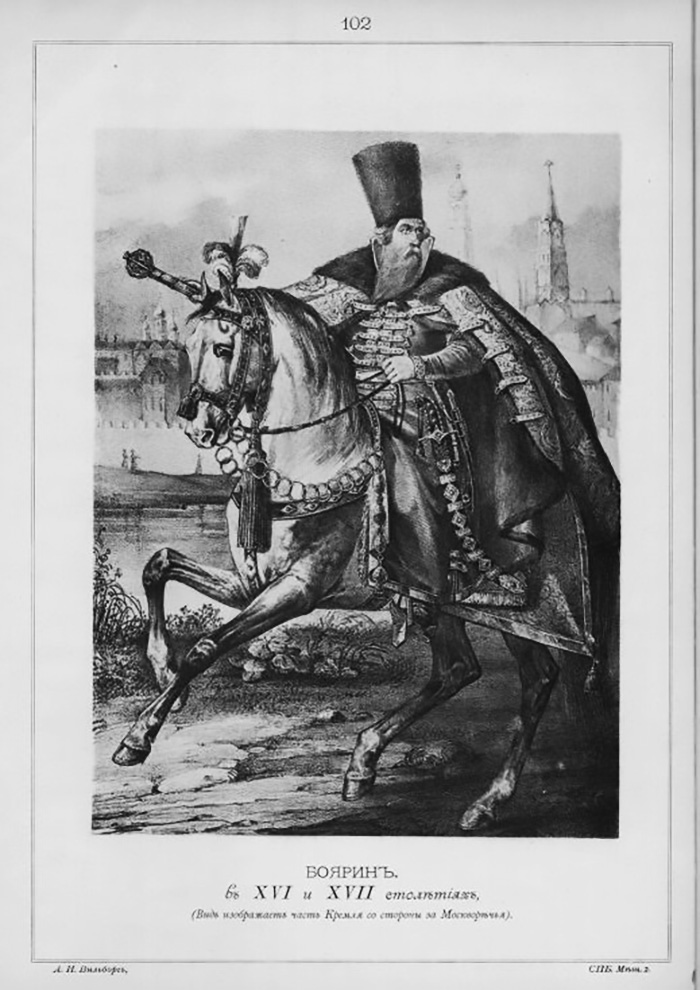

A boyar in XVI and XVII centuries. / Source: Aleksandr Viskovatov

A boyar in XVI and XVII centuries. / Source: Aleksandr Viskovatov

Not a very privileged situation for the aristocracy, right? Nevertheless, the aristocracy was quickly able to simplify their conscription conditions. First, one of two brothers from an aristocratic family was exempted from military service, then the years of service were limited to 25, and in 1762 the aristocracy was fully exempted from conscription. Emperor Peter III made that decision shortly after acceding to the throne in order to gain the aristocracy's support.

For the taxpaying classes, that is, for those paying the poll tax, military service was also reduced to 25 years, but only at the end of the 18th century. In the 1830s, soldiers began serving 20 years. Afterwards, however, a five-year leave of absence was instituted, although one could be called back to the army. Only after the 20-year term was completed was the soldier's military duty considered fulfilled.

Short soldiers with good teeth

Among the lower classes, it was primarily men from large families who were drafted. The idea was not to disrupt the economies of city dwellers and peasants, who comprised the most numerous segment of the population. Doctors examined recruits at special points, and a potential soldier had to be at least one meter and a half tall, without obvious physical defects and with good teeth, which was considered one of the main indicators of good health.

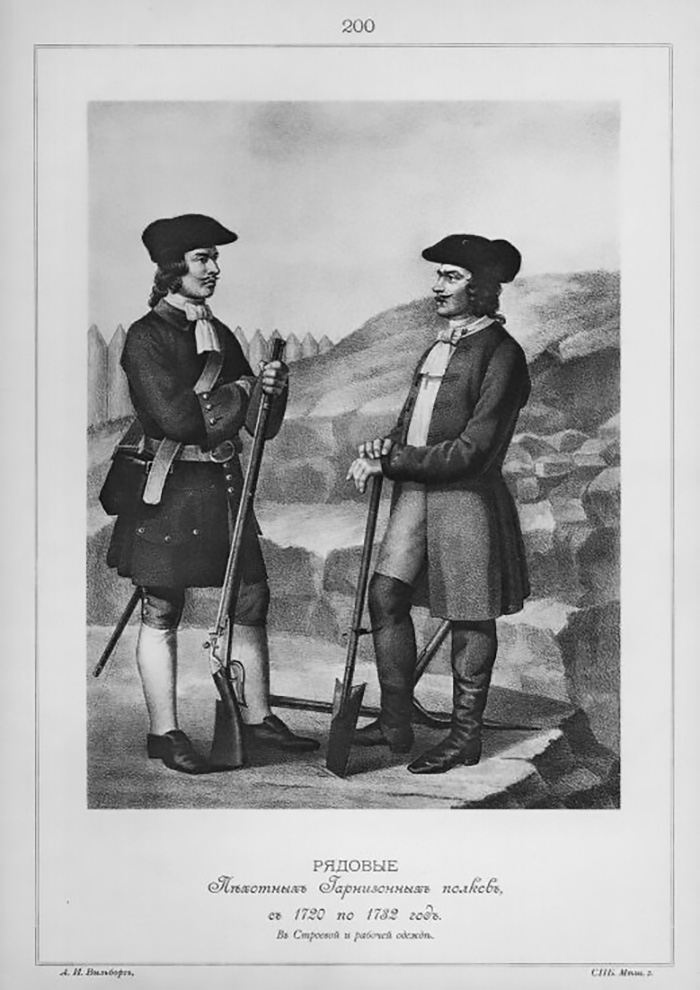

Soldiers of infantry garrison regiments, 1720-1732. / Source: Aleksandr Viskovatov

Soldiers of infantry garrison regiments, 1720-1732. / Source: Aleksandr Viskovatov

Army recruits had their foreheads shaved so that in case of desertion it'd be difficult for them to hide. Those not selected had the back of their neck shaved so they'd not be mistakenly sent to the army instead of someone else.

Soldiers were able to marry, but only with the consent of the regiment commander. The state gave benefits to the soldiers' children and widows, and very often soldiers' children, upon reaching the necessary age, volunteered for the army themselves.

Substitute soldiers

All this, however, didn't popularize the lengthy military service, and many tried to avoid conscription, especially because the opportunity existed. One could pay to send someone else to serve, which was made legal in the Recruiter Charter of 1831.

According to this document, the "hunter," who is the one agreeing to serve for someone else, could go to the army as a volunteer. His departure from the community, however, could not influence his duties before the members of the community and before the state.

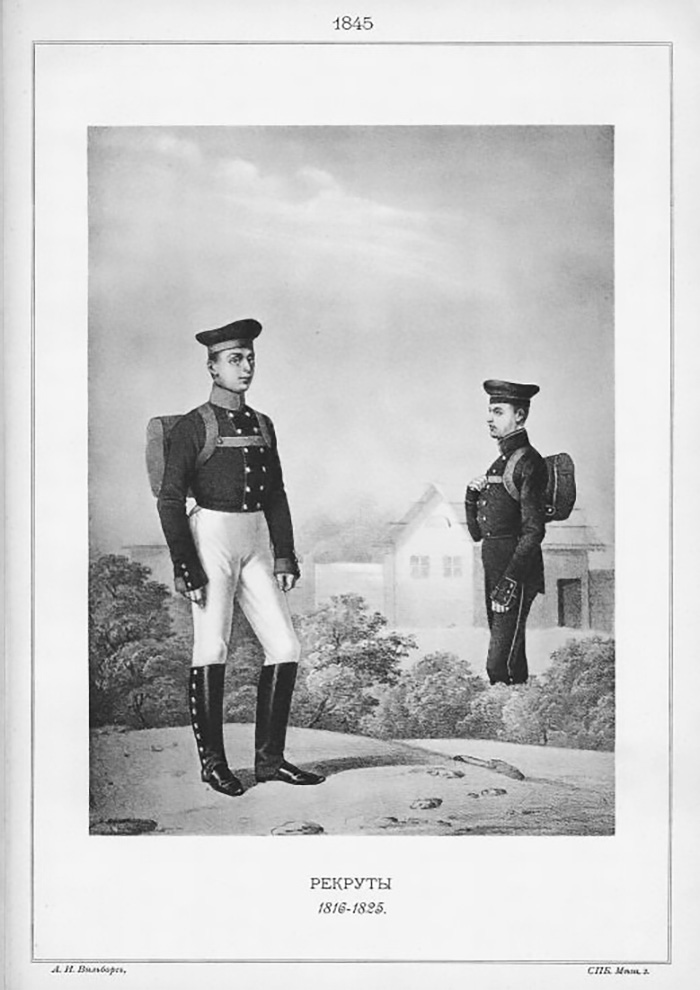

Recruits, 1816-1825. / Source: Aleksandr Viskovatov

Recruits, 1816-1825. / Source: Aleksandr Viskovatov

In order to avoid service, one had to pay 500-600 silver rubles, which was a substantial amount in those days. The "hunter" did not receive the entire amount, although with time his reward became almost two thirds of what the hirer paid.

These conditions were not considered attractive and there were few "hunters" who were willing to serve in the army for decades. In the middle of the 19th century, only about 10,000 "hunters" entered the Russian army, which consisted of more than 1 million soldiers.

The hirer, however, was not the only category which could avoid military service. In the mid 19th century, out of almost 30 million people from the taxpaying classes, six million were exempted from conscription.

'Return of the soldier home' by Nikolai Nevrev, 1869. / Source: Dnipropetrovsk Art Museum

'Return of the soldier home' by Nikolai Nevrev, 1869. / Source: Dnipropetrovsk Art Museum

These included merchants, honorary city dwellers and residents from faraway regions, usually those which had recently been absorbed into the empire and were exempted from military service as a privilege. Thus, by the mid 19th century, Russia had drifted from Peter the Great's idea of universal service.

In need of a large army that could easily be replenished in wartime, Russia in 1874 changed to the draft, basing it on other countries, such as France and Prussia. The traditional notion of the standing army faded into the past along with the hired "hunter," who had been a common figure in medieval Europe.

Read more: From serfdom to freedom: The long and winding road

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox