Censors would starve in modern Russia

Maya Kucherskaya: Russian writers have a prophetic streak

litschool.pro Maya Kucherskaya: Russian writers have a prophetic streak. Source: litschool.pro

Maya Kucherskaya: Russian writers have a prophetic streak. Source: litschool.pro

RBTH: How is the Creative Writing School different from other Russian institutions providing literary education?

Maya Kucherskaya: In fact, there are no other schools of this kind in the country. There are various programs, hobby groups and clubs, but there are no schools – that is, establishments offering comprehensive training on how to write prose, poetry, literary essays and so on.

Our philosophy is that you need more than just inspiration and talent to be a successful writer – you need certain skills and techniques too. There are certain elements of prose and poetry that can be taught. All the creative writing programs in Europe and the United States are built around the same idea, but this simple truth is seen as something new and controversial in Russia.

In our literary tradition authors are more like priests or prophets. What can you teach someone like that? And in fact, the perception is that we should learn from them. They are seen as the arbiters of how to live an honest life, how to build a better Russia. That is exactly how Solzhenitsyn, Tolstoy and Dostoevsky saw themselves, but they were geniuses, so this conception didn’t interfere with their literary work. The same isn’t true of lesser mortals, so as a result modern Russian literature is usually very profound and majestic in terms of the subjects it tackles, but it is far from perfect when it comes to the composition, action and believability of the characters.

RBTH: When did writing become a profession in Russia?

M.K.: That is the crux of the issue: writing is still not a viable profession in Russia. A job is something that puts bread on the table, but an author writing literary fiction might receive the same amount in royalties as a good accountant earns in a month – and that’s after years of work.

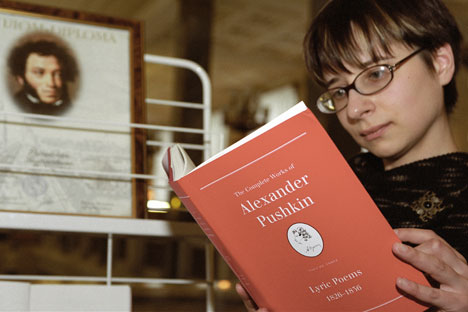

Writers producing popular fiction, 'whodunits' or romance novels, do better, of course. This is a struggle that has been going on for centuries: Pushkin was one of the first to start demanding serious money for his poetry, and some other writers like Tolstoy, Turgenev and Dostoevsky had a good income, but in general Russian writers have always had to work extremely hard to make ends meet.

RBTH: What are Russian writers lacking?

M.K.: The modern Russian prose market is incredibly small and niche. You can count the number of Russian publishers who work with contemporary authors on one hand. In contrast, there are dozens of such publishing companies in Europe and the United States – there’s a reason all creative writing textbooks end with tips on how to find a literary agent. Our market is so small that you simply don’t need an agent to navigate it. An upside of how hard it is to be an author in Russia is that it filters out casual, redundant writers. Only people who truly have writing in their blood try their hand at literary work.

RBTH: Events in recent years have raised concerns of a return to censorship. You came across this recently when a stage play adapted from a short story of yours was recently banned in Novosibirsk.

M.K.: To be honest, I don’t think that a modern censor would find much work even if we did return to genuine censorship. Political satire is virtually non-existent in Russia – it was far more prevalent even during Brezhnev's stagnation era. No-one is even telling Putin jokes.

In terms of literary fiction, apart from the intrepid Dmitry Bykov and his Citizen Poet, no-one really criticizes the government. So, the censors would simply starve in modern Russia, since everything they could be controlling has been eradicated. The state wants to assume greater control over culture, but it hasn’t had much success yet. And even if the government does manage to do it – well, we've seen it all before.

What you'll get is underground culture, samizdat authors, broken lives and burned manuscripts. I simply don’t understand what kind of government would want to see an army of angry neurotics appear in their country.

RBTH: Are there a lot of Russian writers who publish their work abroad?

M.K.: They are few and far between: a dozen, maybe two, but no more than that. The appeal of Russian literature in other countries is highly dependent on the political situation. The sanctions and wars have made people tired of Russia, and it is simply too much for most of them to separate the country’s political image from its literature, to figure out that politics and literature are separate entities.

Read more: 10 quotes to help you convince others you read Russian literature

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox