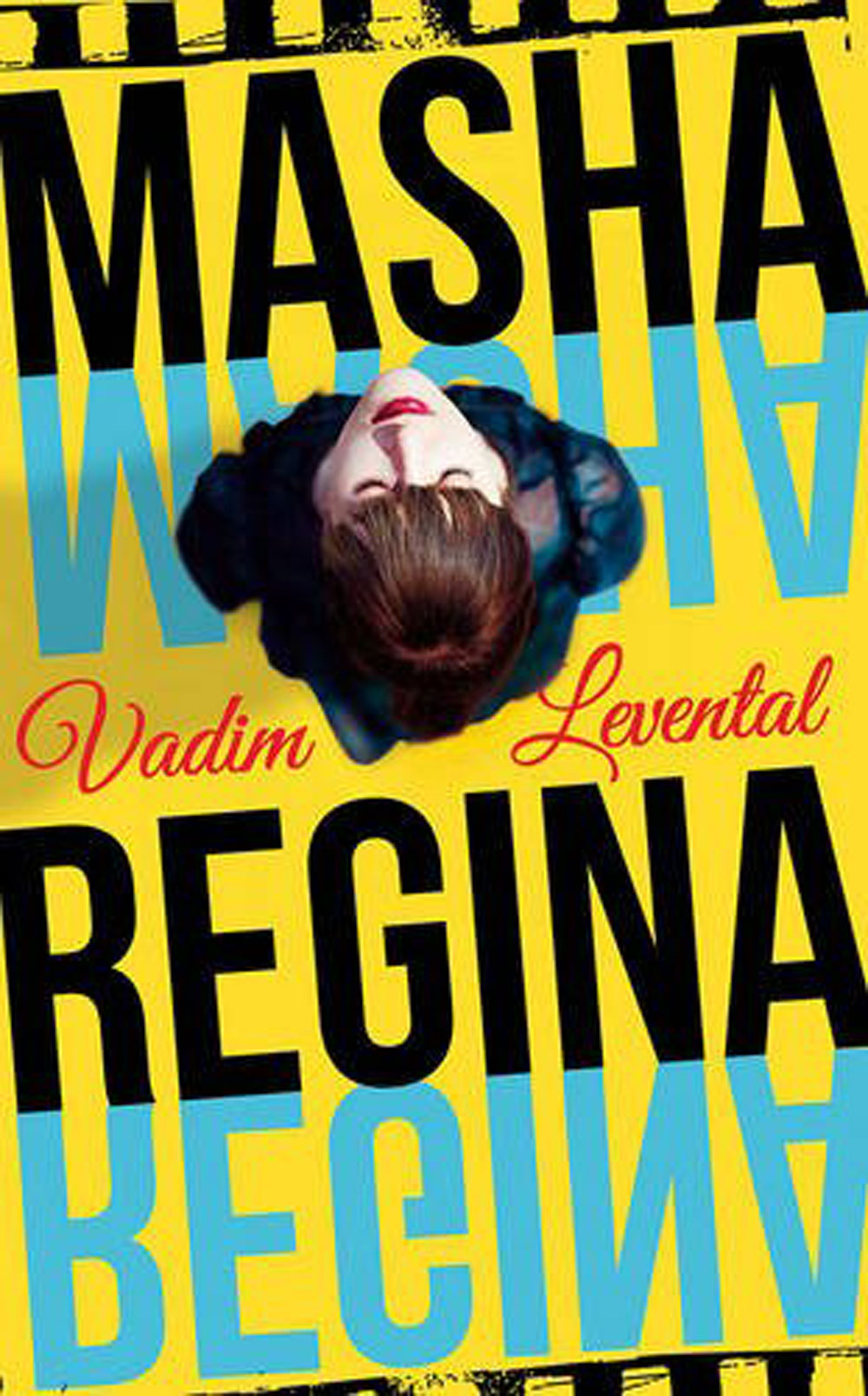

'Masha Regina' by Vadim Levantal: A bold novel in the Dostoevskian spirit

|

| Masha Regin. Vadim Levental. Oneworld Publications (May 10, 2016) |

Growing up in provincial Russia, Masha Regina – artist and future film director – knows she is different from the people around her. “The city where Masha lives is always empty,” writes Vadim Levantal near the start of the story; “… the men here are sluggish and the women are quarrelsome…” Levantal’s heroine is a bold creation; his mixture of philosophical observation and narrative detail is intriguing.

'No matter where I am, I’m in Russia'

In the opening chapter, self-referentially titled “Invention of a Storyline”, Masha’s grandmother dies while her granddaughter is visiting, bringing bean soup. To escape her mother’s ensuing hysteria, Masha breaks away from her provincial roots. The interplay of youth and age, past and future is a powerful force, and the novel describes Masha’s repeated attempts to rid herself of the past and recreate herself. The day where she wanders for the first time through St. Petersburg’s embankments, streets and avenues, “whispers hi to angels and caryatids, winks at lions and stern commanders” leaves her feeling: “she was born today”.

Masha Regina’s psycho-geographical elements are some of the most compelling. St. Petersburg is a pervasive presence, haunting Masha “like radiation, like salt permeates her mother’s cucumbers”, and while the action roves from St. Petersburg to Berlin, home and away again, she declares “no matter where I am, I’m in Russia.” The novel grapples with issues of emigration, with universal themes – fame, religion, politics, feminism – as well as more specific “Russian problems”.

Cultural quotations

Masha’s lecturer A.A. breaks off from a literature lesson about Gogol’s Nevsky Prospect to tell the students: “You live in the city where European culture found meaning!” Her first film is a portrait of rainy Petersburg, conceived after talking to A.A. in a smoke-filled kitchen about Bitov’s Pushkin House, an intense and allusive Soviet novel.

Masha Regina is similarly populated with cultural quotations from the Iliad to Star Wars, Gogol to The Godfather, fairy tales to porn sites, Don Quixote to computer games. Levantal’s work returns regularly to the “Dostoevskian spirit”, even as it spans both Shakespearean allusions and social media (“nothing drives people apart like daily status updates”).

In her acknowledgements, translator Lisa Hayden comments on these references “woven into the novel.” Her English version of this complex tapestry is, as ever, a delight, tackling multiple challenges from colloquialisms (“a drunk chick is not in charge of her twat”) to tongue twisters (“by the burbling river bank we bumblingly bagged a burbot”). Hayden’s thoughtful brilliance in this book, as in her blog and in other recent translations including Eugene Vodolazkin’s Laurus, helps illuminate contemporary Russian literature for Anglophone readers.

'In deafening loneliness'

Levental often pre-empts or summarizes his own narrative with a catchphrase: “It will be like this”, “and it was like this”, he writes. At key moments he switches to the first person as Masha speaks directly, her stream-of-consciousness unraveling through time. She has echoes of Andrei Platonov’s free-spirited Happy Moscow or D.H Lawrence’s modernist passions, and her three lovers – the tempestuous cameraman, the older teacher and the German actor – pull the plot in different directions. This uneven tension is occasionally frustrating: Levental’s novel is too meandering to be really gripping, but too intense to be relaxing.

The novel triumphs through imagery rather than action – as Masha’s fictional movies do. Consciousness is a collage of moments that sometimes contradict each other, fragmenting “the wholeness of human identity through time.” Levental repeatedly returns to metaphors of creativity – novels, poetry, film.

Images from Fanny and Alexander or Battleship Potemkin sail through the text, gathering around the central idea that we discover ourselves (and lose ourselves) through art. As young Masha reads children’s books, “the stories are always about her”. As we read Masha’s stories, we realize they are often, chillingly, about us. In Levental’s multifaceted work, there is a bleak connecting thread: “the story of how a person progresses toward the absolute finale with accelerating speed and in deafening loneliness.”

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox