Why Shakespeare is an honorary Russian

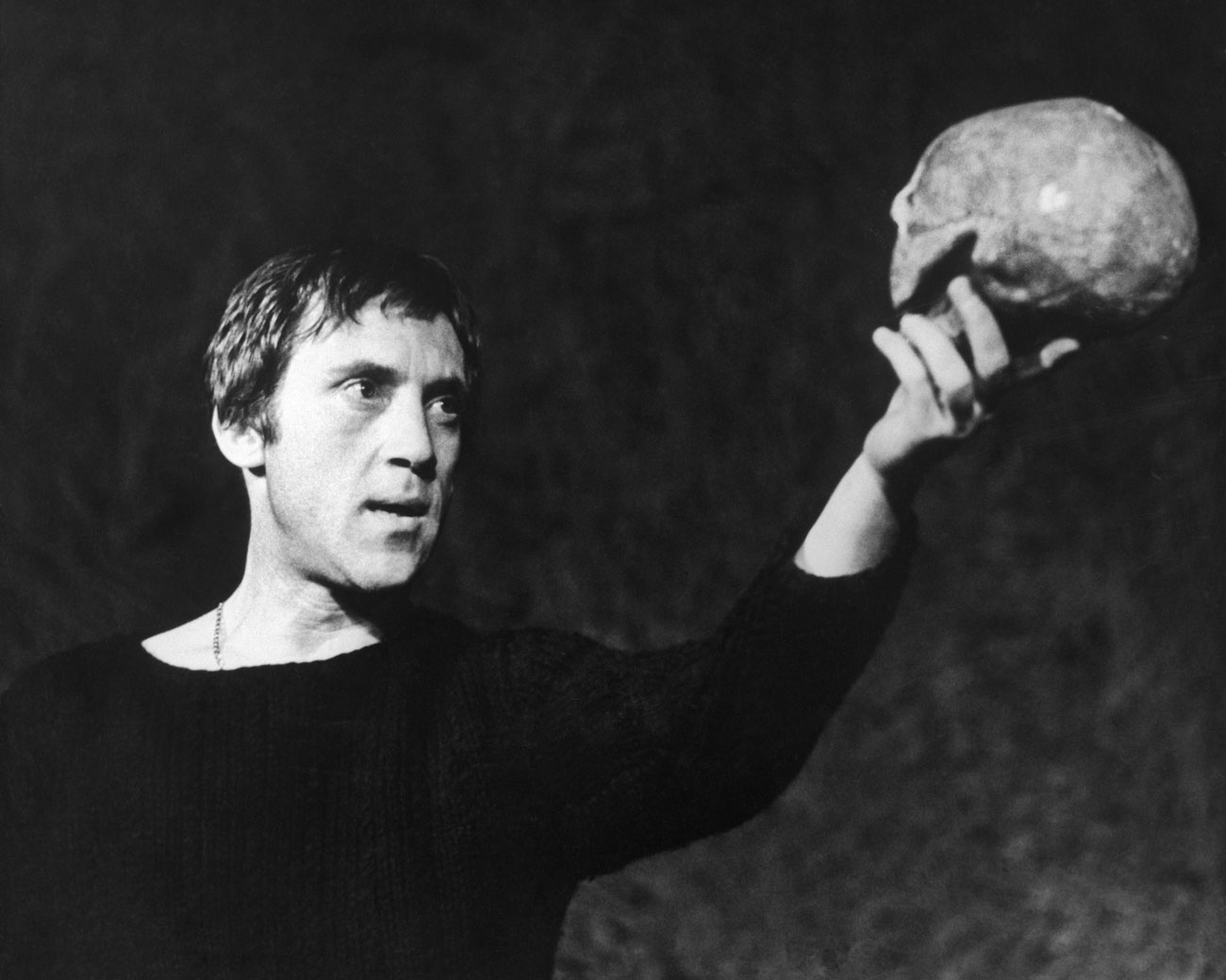

Soviet actor Vladimir Vysotsky as Hamlet at the Moscow Theater of Drama and Comedy on Taganka.

TASS“You are among us, you’re alive,” the great Soviet-era novelist and poet Vladimir Nabokov wrote in his poem, Shakespeare. Imagining a “hundred-mouthed, unthinkably great bard” strutting from Elizabethan times into the modern era, Nabokov captured Russia’s enduring fascination with Shakespeare. His words still resonate in Russia today as appetites for classical English literature remain undiminished.

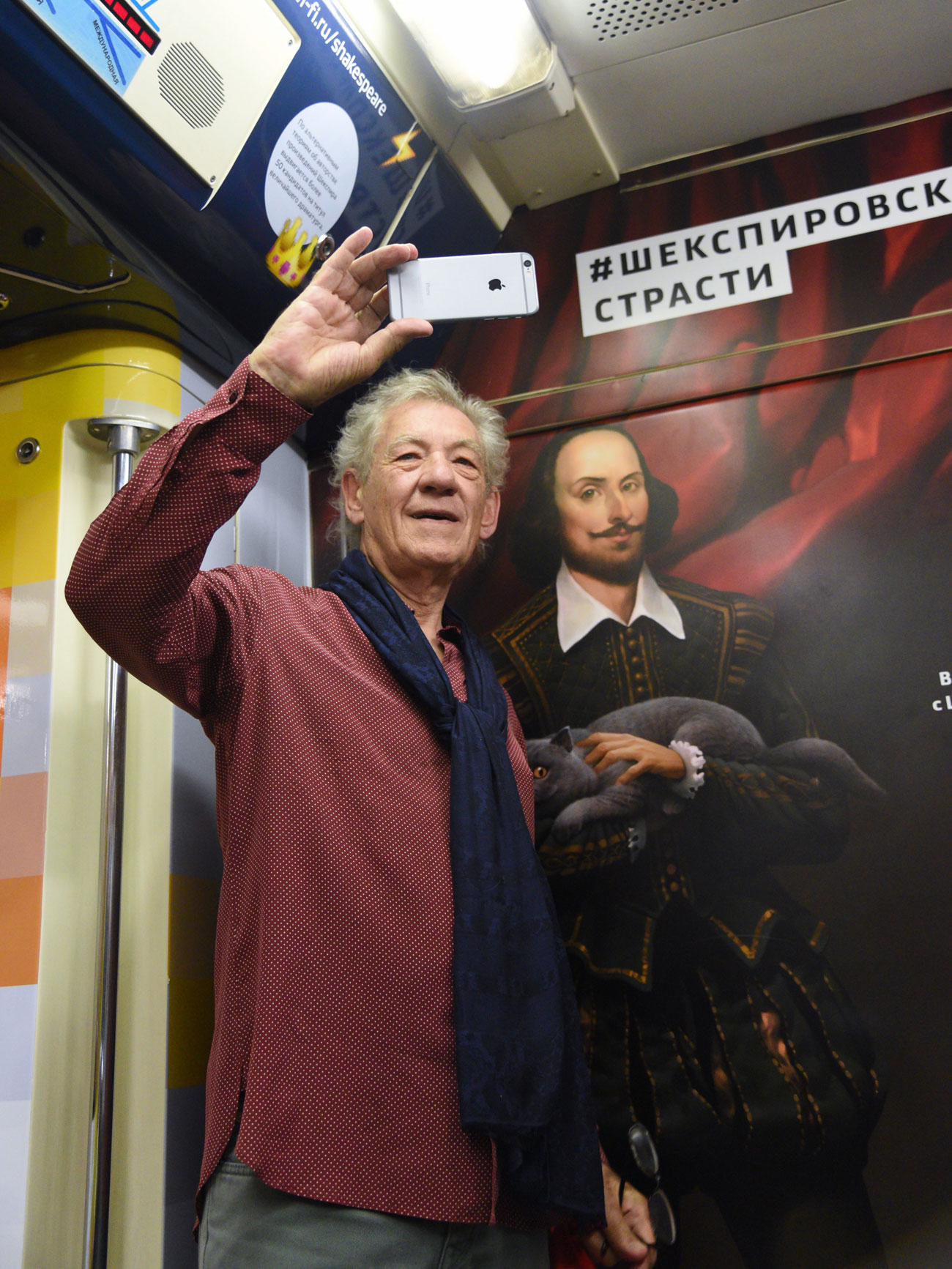

Earlier this year, commuters in Moscow were greeted by an unusual sight: a metro train brightly decorated with quotes and characters from Shakespeare’s plays.

Ian McKellen rides Shakespeare train in Moscow metro. Source: Vasily Kuzmichonok / TASS

Ian McKellen rides Shakespeare train in Moscow metro. Source: Vasily Kuzmichonok / TASS

A lookalike of a cat once pictured with Shakespeare has boarded a special train of Moscow metro. Source: Press photo / Moscow metro

A lookalike of a cat once pictured with Shakespeare has boarded a special train of Moscow metro. Source: Press photo / Moscow metro

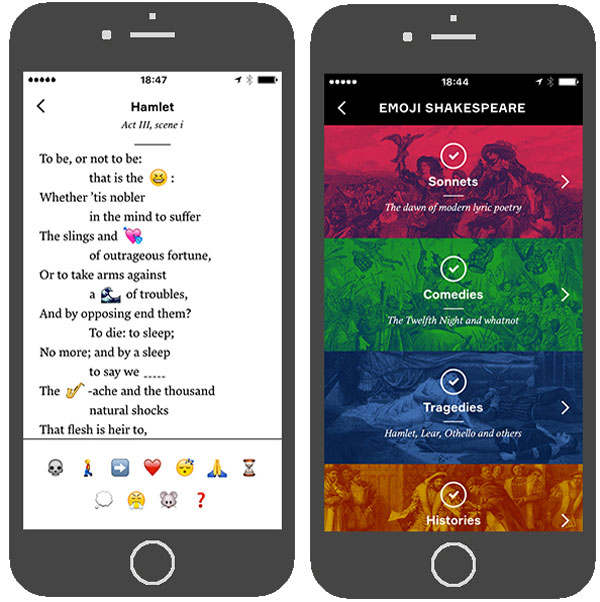

As part of celebrations for the UK-Russia Year of Language and Literature 2016, Moscow’s Shakespeare Train shows how Russian audiences continue to encounter the Bard in original and unexpected ways, from groundbreaking stage productions to Arzamas Academy’s Emoji Shakespeare app, which was released this year.

Emoji Shakespeare is an English/Russian app produced by the educational website Arzamas. Users fill in the blanks in lines with emojis. Source: Screenshot from Apple store

Emoji Shakespeare is an English/Russian app produced by the educational website Arzamas. Users fill in the blanks in lines with emojis. Source: Screenshot from Apple store

Shakespeare’s influence on many Russian writers is undisputed. Speaking at the launch of the UK-Russia Language and Literature initiative, Michael Bird, head of the British Council in Russia, suggested Shakespeare’s importance for Russian literature is so great he is “practically a Russian writer himself”. Authors and playwrights as diverse as Pushkin, Chekhov, Pasternak and Nabokov have all drawn on Shakespeare’s example in crafting their own classic works of Russian literature.

Admirers and doubters

Although Shakespeare's influence in Russia was well established by the 19th century, he was not universally liked. Indeed, Leo Tolstoy declared Shakespeare’s plays “immoral” and warned against an “epidemic” of “Shakespeare-worship” infecting authors across Europe. Peter Sekirin’s biography of Anton Chekhov relates an anecdote in which the elderly writer, who was bedridden with illness, whispers to Chekhov: “You know, I hate your plays. Shakespeare was a bad writer, and I consider your plays even worse than his.”

However, Chekhov appears to have been unmoved by Tolstoy’s comments, explaining to Ivan Bunin that “Shakespeare irritates him because he is a grown-up writer, and does not write in the way that Tolstoy does”.

For Tolstoy, comparisons with Shakespeare were not regarded as a compliment. But other key figures in Russian literature vigorously encouraged the study and adaptation of Shakespeare. “Read Shakespeare, that is my refrain,” Alexander Pushkin wrote while composing his play Boris Godunov. Published in 1825, the play merges Shakespearean themes and characters with Russian context and history. Nearly 10 years later, Pushkin began translating Shakespeare’s Measure for Measure, but the project transformed into a poetic adaptation called Angelo – an example of how Shakespeare’s plays have encouraged new, original forms in Russian literature.

Deception and uncertainty

Shakespeare’s works have been a touchstone and inspiration for many of Russia’s most influential authors. In its final pages, Pasternak’s masterpiece Doctor Zhivago includes the poem Hamlet. It concludes: “I am alone; all round me drowns in falsehood, life is not a walk across a field.” The stanza brings together the deception and uncertainty of Shakespeare’s Hamlet with the fate of Pasternak’s own tragic hero. Art eventually converged with life when the poem was recited by mourners at Pasternak’s own funeral, despite being banned by the Soviet regime at the time.

Characters from Shakespeare’s plays have often been used to give voice to political and social commentary in Russian literature. When Anna Akhmatova imagined Ophelia’s perspective in her poem Hamlet, she joined a worldwide tradition of authors choosing to rework Shakespeare’s lines and characters for new forms and situations.In the 19th century, Ivan Turgenev’s Hamlet of Schigrov District (1849) and King Lear of the Steppes (1870) showed the momentous synergy between Shakespearean themes and rural Russian society and landscape. Turgenev admired Shakespeare for his universality, and praised the playwright’s capacity to capture “life itself... so truly rendered that everything appears to be occurring while you watch”.

As with Turgenev’s writing, Nikolai Leskov’s novel Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk relocates Shakespeare to the Russian steppe, reimagining Shakespeare’s anti-heroine as a provincial merchant’s wife who reaches violent extremes of frustration and vengeance. Macbeth had been banned from performance until 1861, and the enduring social charge of Leskov’s reworking is indicated by reactions to Shostakovich’s wildly successful opera based on the novel in 1936. Joseph Stalin walked out of the performance, and the opera was condemned as “petit-bourgeois ‘innovation’” in a Pravda article titled “Muddle instead of Music.” Such reactions show the continuing power of Shakespeare to upset and provoke the social order.

From queen to screen

Although Shakespeare has high status in Russian literary culture today, in the 17th-18th centuries his plays were often encountered via French or German translations and only found limited audiences. Shakespeare’s first translation into Russian was Alexander Sumarokov’s Hamlet in 1748, based on a version in French; and Empress Catherine II translated The Merry Wives of Windsor from German in 1786.

The plays faced the challenge of politically turbulent times: Sumarokov’s Hamlet had to tiptoe around the historical parallel of a queen who had recently removed her husband, while Catherine banned Karamzin’s Julius Caesar for political reasons in 1794.

Pavel Mochalov played Hamlet in the late 1830s. Source: archive photo Pavel Mochalov played Hamlet in the late 1830s. Source: archive photo |

It was not until the early 1800s that Russian “Anglomania” brought a surge in translations and performances that firmly established Shakespeare’s place in Russian culture. Stagings of Shakespeare in the 19th century brought rapturous crowds and passionate discussion. The critic Vissarion Belinski’s essay On Hamlet describes celebrity actor Pavel Mochalov, whose father had played Shakespearean roles in a serf theatre, transfixing his audience with the “power and zeal” of his performance.

Shakespeare’s literary importance continued into the Soviet era and well beyond. A century after Pavel Mochalov’s emotive turn as Hamlet, Boris Pasternak spent much of 1940 translating the play. This translation became the script for a trailblazing 1964 film, directed by Grigori Kozintsev with a score by Dmitri Shostakovich. Reviews praised the film’s striking scenery and the “movements, expressions and passionate moods” of performers.

Hamlet (1964) - Directed by Grigori Kozintsev. Source: MrBongoWorldwide / YouTube

In his 1962 book Shakespeare, Time and Conscience, Kozintsev had described Shakespeare as “our contemporary”, and his cinematic versions of Hamlet and King Lear joined Les Kurbas’s fearsome 1924 cubist-expressionist Macbeth in drawing Shakespeare into the power struggles of the Soviet era. Shakespeare’s latest Russian manifestation is part of a tradition that looks set to continue in one of the world’s most highly literate societies.

Read more: 5 great foreign writers who were influenced by Russia’s literary giants

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox